Walkabout: Rufus L. Perry and Son, Brooklyn Pioneers, Part 3

Editor’s note: An updated version of this post can be viewed here. Rufus L. Perry, Jr. was one of Brooklyn’s best known attorneys in the early 20th century. He represented a varied group of clients in both criminal and civil court. He was a true son of his father, a respected clergyman living in what…

Soldiers of the 369th Infantry Regiment, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, in 1919. Photo via National Archives

Editor’s note: An updated version of this post can be viewed here.

Rufus L. Perry, Jr. was one of Brooklyn’s best known attorneys in the early 20th century. He represented a varied group of clients in both criminal and civil court. He was a true son of his father, a respected clergyman living in what is now Crown Heights North. The fact that the Perrys were African American is just part of this forgotten history. We met the father in Part 1. The son’s early accomplishments were chronicled in Part 2. Our story continues:

Rufus Perry, Jr. spent his entire life rising above the expectations of the white world around him.

He was the Valedictorian of his NYU Law School class and spoke at commencement in 1891. He could speak and write fluently in five languages. None of his classmates could claim that ability. He wrote his bar exams in Latin, probably sending more than one professor back to his dictionary.

He opened his law practice after passing the bar, representing black clients, which was expected, but he had a full roster of white clients as well, both male and female.

In 1910, at the age of 26, Rufus married 24 year old Lillian Sylvia Buchacher. Unfortunately, no other information is available about her. All we know from census records is that she and her parents were all born in New York City.

Interracial marriages were few and far between back then, and were not looked at favorably at all. Two years later, Rufus converted to Judaism, taking the Hebrew name “Raphael.”

He was black, Jewish, with a white wife, and with way too much smarts for the son of a former slave. When he decided to go into Brooklyn politics, his friends and enemies lined up accordingly. But first, a little background:

Brooklyn Standard Union, 1922

In the years before World War I, the African American community in the United States was struggling to rise above overt discrimination in the South, and a more covert racism in the North.

Although slavery had ended with the Civil War, most Southern blacks were still on plantations, now as sharecroppers tied to the land by debt. Illiteracy was still high, and other opportunities were low.

The KKK and other hate groups terrorized people who got out of line, and lynching and injustice was more common than real justice. A black man still couldn’t look a white man in the eye without risking reprisals later.

Here in the North, that sort of overt racism was seen far less often, but economic and social equality was not yet possible for most black folks. However, as a group, black people were not sitting around waiting for equality to be bestowed upon them.

Even during pre-Civil War days, there had been organizations and societies dedicated to self-improvement. The black church was a longtime leader in this movement.

In 1909, W.E.B. DuBois — the first black man to get a PhD from Harvard — and a group of black and white activists founded the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — one of the most important and powerful civil rights organizations in America.

DuBois was the voice of “the talented tenth,” his name for the elite in the black community consisting of educators, professionals, and the like. He believed that this group could help open the doors of equality and opportunity for the rest of the black community.

A man like Rufus Perry, Jr. was certainly one of the “talented tenth.” His educational accomplishments, his victories in court, and his acceptance in the white legal community — albeit grudgingly at times — was proof that blacks were as capable of “higher” professions as anyone.

Brooklyn’s black community was also well aware of Perry’s talents and skill. In April of 1911, the Brooklyn Eagle printed a letter from Clarence A. Smith, an African American living on Lafayette Avenue.

“Why doesn’t Brooklyn have a Negro Magistrate?” Smith asked. He went on to note that Brooklyn had 16,000 colored voters, (this was before women could vote) and no representation. He felt that black support for New York Mayor Gaynor deserved to be rewarded by appointing Rufus Perry as a Magistrate.

That question would go unanswered. In the meantime, Mr. Perry was still representing clients and cases that touched upon the black experience in the New York area. He was also thinking outside of the law, and buying investment property.

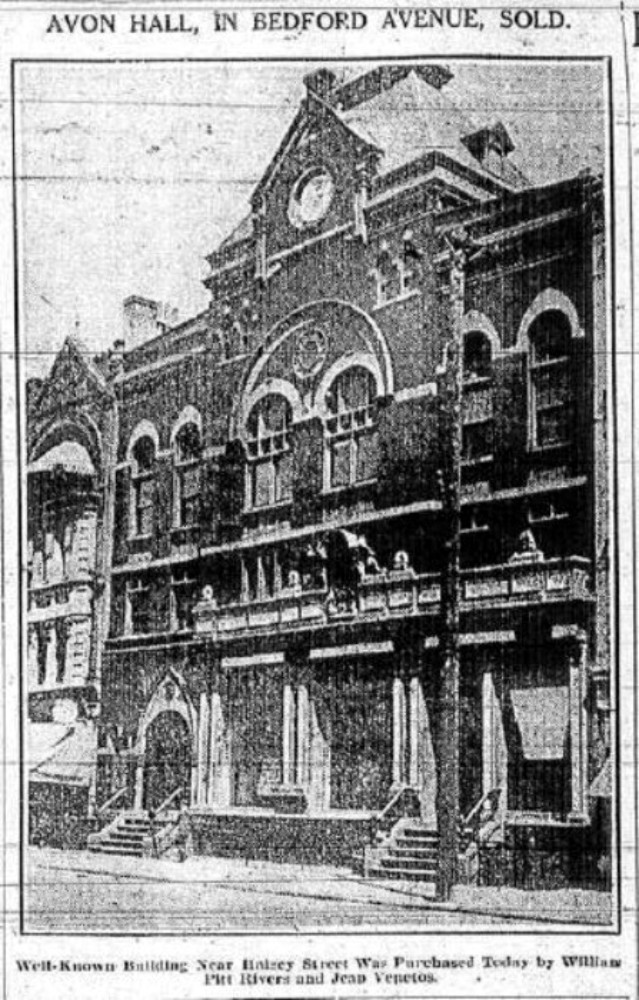

In 1914, Perry was the president of a group of black investors who purchased Avon Hall, a three story building built as an event space and meeting hall. It was located at 1217-1221 Bedford Avenue, near Fulton Street.

Avon Hall, Brooklyn Eagle, 1914

The building, built in 1885, had an auditorium, a ballroom and a bowling alley in the basement. Today, it no longer stands. It was replaced by an automobile showroom in 1919. The newer building was a Building of the Day. The consortium had the building for two years, and then sold it at a tidy profit.

In 1915, while this was going on, Perry aided Assemblyman Fred G. Milligan, Jr. and Senator Alfred J. Gilchrist in introducing legislation to stop the practice of “Negro Ball Dodging.”

One of the most popular attractions at Coney Island arcades was to hire black men to stick their heads through a canvas or plywood opening, while people payed money to throw baseballs at them. Desperate men would take the jobs, risking serious injury, even death.

The men wanted to make the practice illegal, and to make it a misdemeanor for anyone to throw the ball, or act as a target. The bill had wide support from the black community, as well as the general public. Hopefully, it was passed.

However, in 1917, Rufus Perry’s fast moving legal career came to a grinding halt. He was disbarred because of a trumped up charge, with much ado about a technicality.

The Rev. Rufus Perry, Sr. owned a property at 1014 St. Marks Avenue, up the street from their home at 999 St. Marks. In 1895, just before his death, Rev. Perry wanted to transfer the deed to his wife.

According to his son, the elder Perry was so feeble at the time that he had his lawyer son rewrite the deed, and sign it for him. He then traced over the signature, thereby authorizing it. He died soon after.

Perry did not immediately record the deed, which was signed in 1895. When he finally did, he couldn’t find the original, and so filed a copy. That copy was dated 1895, but the paper had a watermark of 1896. He later found the original, and filed that, as well, intending to have the copy removed, but he forgot.

In 1917, Mrs. Annie Perry Mills, Rufus’ sister, wanted to sell the property. When the buyers’ had a title search done, the title company came upon the re-written deed as well as the copy, and questioned their authenticity.

Perry explained what he had done. He also noted that he personally had paid the mortgage and the interest on the property for almost twenty years. It was now completely paid off.

The Brooklyn D.A’s office and the Brooklyn Bar Association were both looking into the case. They accused him of forging his father’s signature.

The D.A. wanted to charge Perry with both forgery and perjury. The case went before the Grand Jury, which determined that there was no perjury, and no forgery. There would be no criminal charges.

But the Bar Association took a more jaundiced view. They ruled that Perry had indeed forged the signature on a legal document, and thereby acted in a manner unworthy of the Bar. They voted disbarment. His legal career appeared to be finished.

Perry immediately appealed, but the first appeal was unsuccessful. In 1918, the Appellate reviewed his case, and overturned the decision. But they suspended him for five years, citing his “good conduct” before all of this mess.

During his suspension, Perry was busy helping the cause of black soldiers in World War I. The army was still segregated, and black soldiers were not accorded the rights they should have had. They had inferior equipment, lodgings, and other basic accoutrements. Returning veterans, especially wounded ones, found themselves without the same resources as white veterans.

Perry was somehow able to arrange a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson, in Washington, DC. The two men sat for an hour at the White House, while Perry presented his case for the African American soldier.

The result was a $425,000 appropriation by the US Government for the improvement of conditions and equipment for the Colored troops. Not everything one could ask for, but a substantial realization by Wilson that more needed to be done.

In 1922, Perry’s suspension was lifted, and he was once again able to practice law. He got right back to his clients, old and new, and continued to make the papers.

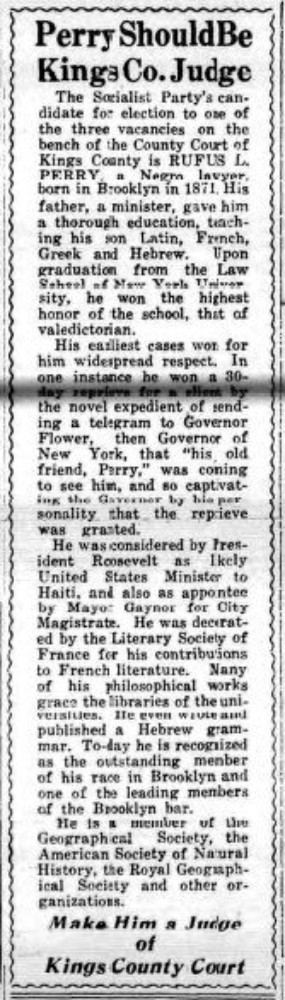

In 1927, a group of supporters encouraged Perry to run for a judgeship in Brooklyn on the Socialist Party ticket. They took out an ad in the paper which cited his status as Valedictorian of his Law School class, his many achievements in court, as well as his work in French Literature.

Brooklyn Standard Union, 1927

He had been made a member of the Societé Academique d’Historie Internationale, and had been awarded a diploma and a Gold Medal for his accomplishments. If anyone was worthy of being a judge, it would be a man of the caliber of Rufus Perry.

He did not win.

On June 6, 1930, after a two-week illness, Rufus Perry, Jr. died at his home at 1427 President Street. The article in the Brooklyn Standard Union announcing his death noted that he was the famous colored lawyer, the son of the Reverend Rufus L. Perry, Sr.

The article went on to note that he “attracted nation-wide attention 18 years ago when he embraced the Jewish faith.” He had been a leader of Brooklyn Negroes for the Republican Party, but had then become a Democrat, and then ran for County Judge as under the Socialist Party.

The article did not note any of his many accomplishments – not his formidable skill in languages and scholarship, his membership in many important organizations and clubs, his meeting with presidents or his representation of foreign leaders. Nor did they mention any of his noteworthy court cases. Thankfully, they didn’t mention his disbarment, either.

But they did note that he was survived by his widow, Lilly S. Perry, “a white woman,” and a brother and sister. He and his wife never had any children. His funeral was at home, followed by burial at Mt. Carmel Cemetery. He was sixty years old.

A full and fascinating life reduced to private matters of faith and who he married.

Today, the Perry men, father and namesake son, would be even more forgotten, had it not been for the efforts of Freedom Williams, the great-great grandson of Rev. Perry. Mr. Williams. He has established a website highlighting some of the accomplishments of his ancestors, and important biographical information. It can be found here.

Rufus Perry Junior’s many cases would make a fascinating study. Hopefully the opportunity to further investigate this matter will arise.

Part 1: Rufus L. Perry and Son, Brooklyn Pioneers

Part 2: Rufus L. Perry and Son, Brooklyn Pioneers Continued

Part 3: Rufus L. Perry and Son, Brooklyn Pioneers Conclusion

1427 President Street, Nicholas Strini for PropertyShark

Fascinating story. Thank you for sharing…would love to know more!