Walkabout: It’s Nice to Be Ice, Part 3

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 4 of this story. On January 1st, 1898, Brooklyn officially became a part of Greater New York City. The consolidation of the five boroughs into one city, what many in Brooklyn called “The Great Mistake,” was now a reality. Brooklyn was no longer an independent city. There were…

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 4 of this story.

On January 1st, 1898, Brooklyn officially became a part of Greater New York City. The consolidation of the five boroughs into one city, what many in Brooklyn called “The Great Mistake,” was now a reality. Brooklyn was no longer an independent city.

There were a lot of good reasons to consolidate, as well as equally good reasons not to. One of the main reasons many Brooklynites did not want to be associated with Manhattan was political.

Manhattan, throughout most of the 19th century, was run by Tammany Hall, the powerful and increasingly corrupt Democratic Party patronage machine.

To be sure, Brooklyn had its political corruption on both sides of the aisle, as well as its Tammany Hall bosses, but the Republicans managed to control the city from the end of the Civil War until the waning years of the 19th century, keeping Tammany Hall at bay.

Everyone knew they ran Manhattan politics, and many prominent Brooklynites didn’t want to have anything to do with them. But it was not to be.

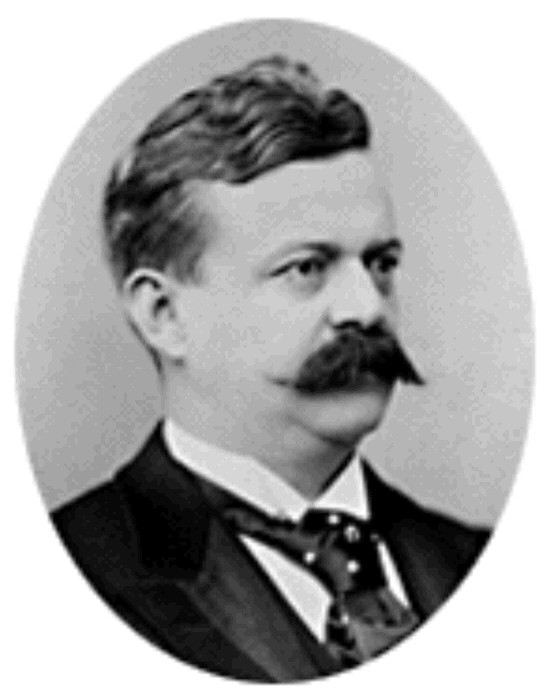

Consolidation had passed the legislature well before 1898, and the winner of the 1897 mayoral election always knew he’d be mayor of Greater New York City. Reformers eager to get rid of Tammany Hall put up wealthy Brooklyn businessman Seth Low as their candidate for mayor.

He was the son of one of Brooklyn’s oldest and wealthiest merchant families, and was well respected as a man of integrity. Opposing him would be Robert Anderson Van Wyck, also a son of old New York stock. His Dutch ancestors had helped settle Brooklyn and Queens back in the 1600s.

Van Wyck, like Seth Low, was a Columbia College graduate, and a lawyer. He was a social animal, a member of many of the city’s best clubs, and was a prominent Freemason.

He had gone into politics as a Democrat, and was elected Judge of the City Court of NY, and later Chief Justice of that same court. He resigned from the bench when Richard Croker, the Tammany Boss of NYC, picked him as the Democratic candidate for mayor.

Van Wyck might have liked to think that he was asked to be the Democratic candidate because he was the most qualified for the job, but the truth was that Tammany Hall picked him because they knew he wouldn’t give them any problems while Croker and cronies went about really running the city.

He was a colorless and rather boring man with a big ego. With Tammany’s backing, he easily won the election, and became the first mayor of the metropolis of New York City.

Everything was going along well for Mayor Van Wyck for his first two years. He actually accomplished some good things. He oversaw the mammoth efforts to consolidate city government and agencies, and he instituted the first city subway, the IRT, and proposed the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel.

His efforts in the area of mass transit were his finest legacy, leading to the Van Wyck Expressway being named for him years later. But his association with Charles W. Morse, the “Ice King of New York” would be his undoing.

As we saw in the last two chapters of this story, Charles W. Morse and his company, the Consolidated Ice Company, had taken over the ice trade to New York City. A history of ice making and the city’s dependence on it is covered in Part One, and Morse’s rise to power is the topic of much of Part Two.

Ice was as important to the economic life of the city as fuel or fresh water. Entire industries depended on it to operate their businesses, the food industry needed ice to function, and private homes, from the largest mansions to the most humble tenement apartment, needed ice to keep food chilled and edible.

He who controlled ice controlled the well-being of New York, and that man was Charles W. Morse.

By 1895, he had bought out almost all of New York, Brooklyn and Long Island’s independent ice companies. He controlled the ice coming from the rich ice fields of the Hudson River and the rivers of Maine, where he had gotten his start.

He was now in the position to dictate prices, and he began raising them. In 1896 he bought out his last competitor, the huge Knickerbocker Ice Company, which produced the region’s best and most pure ice, cut from Rockland Lake in upstate Rockland County.

His empire was now complete. If the city wanted ice, they were going to have to pay.

Monopolies were nothing new; companies like John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil had tried to fix the price of fuel by buying out all of his competition and forming “trusts” which controlled the price and availability of fuel, and were eventually thwarted by the passage of the Sherman Anti-Trust Law of 1890, and laws that followed from that.

Morse’s Consolidated Ice Company had also become a publically traded “trust” in 1899, and was now called the American Ice Company.

Under the umbrella of the trust, his former competitors were still operating as separate entities, but they were all controlled by Morse. He dictated his prices, his terms, and his way of dealing with the city’s desperate customers.

The newspapers could howl in righteous indignation and call for investigations, lawmakers could demand new legislation, businesses could complain, and individual customers would dig deep to find the extra money to buy a block of ice that now cost twice what it had cost the week before, but in order for this to really work, it needed the blessing of government.

In Mayor Van Wyck, Morse found the ideal man; one who could turn a blind eye when offered the right sort of encouragement.

In 1900, the American Ice Company decided to double the price of ice across the board. It was May of that year, and supplies were actually over capacity after an exceptionally good ice harvest the winter before. But no matter, AIC told wholesale customers that there was a shortage and the price of ice was going up.

Through Van Wyck’s influence, Morse not only had a monopoly on the ice itself, he had exclusive rights to the ports and piers of New York City. Not a block of ice from any other company could legally be off-loaded in NYC, only AIC ice was allowed.

Well, this did not go down well with anyone. The public was in an uproar. Van Wyck threw up his hands and said it was out of his control, and perfectly legal. The press, specifically the New York World, and the mayor’s political enemies decided to do a bit of investigation, and their findings were amazing.

It seemed that Robert Van Wyck, who made only $15,000 as mayor, and was not a particularly wealthy man, was in possession of $680,000 worth of American Ice Company stock. On top of that, much of it was preferred, not common, therefore worth more, and was stock that he did not have to pay for. Whoops!

The investigation continued and led to a court hearing in Brooklyn Supreme Court, presided over by Justice William Gaynor. Van Wyck was in between a rock and a hard place. It was quite evident that he had been bought by Morse’s AIC, and was not the mayor of the people.

He was not protecting the thousands of poor people in the tenements who could in no way afford the price gouging, and the lack of ice put them in more danger of hunger and sickness than ever.

These people, the waves of immigrants, especially the Irish, were Tammany Hall’s main constituents. The bosses had remained in power for so long because the Irish and other immigrants had been helped with jobs, favors and reforms in return for votes and an army of Tammany foot soldiers.

Van Wyck, as a Tammany man, had been biting the hand that fed him, and the body politic was not happy.

Worse than that, the investigation also revealed that Tammany, too, had been playing both sides. Its leadership was also heavily invested in American Ice Company stock. Boss of bosses Richard Croker had $250K of stock in his wife’s name.

His underboss, John Carroll, had $500K. Van Wyck, as noted, had $680K, and Van Wyck’s brother, Augustus, owned $200K worth of AIC stock.

Brooklyn boss Hugh McLaughlin owned a nice chunk of stock, and so did the dock commissioners of NYC, including Charles F. Murphy, the man who would one day take over Tammany from Croker. The dock commissioners had been the enforcers of the ice wars, preventing any other company’s ice from being off-loaded in the city.

Croker’s business partner, Peter Meyer, got his share, and in bi-partisan fairness, so did Republican Frank Pratt, the son of Republican state party boss, Senator Thomas Pratt. It also came out that Mayor Robert Van Wyck and deputy party boss John Carroll had both been guests of AIC president Charles Morse at his home in Maine, and had toured his ice factories.

During the hearing, Van Wyck insisted that he had bought the AIC stock, and it was not a gift. He said that as mayor he came into contact with influential people, and had met Mr. Morse, who persuaded him to invest in his company. He was in possession of 4,300 shares, but he had borrowed the money to buy them.

He was in no one’s pocket. Yes, he had gone to Morse’s home in Maine, but it was by accident. He was with Morse on a trip upstate, and Morse said that since they were so close to Maine, he’d like to see his children, whom he hadn’t seen in nine months, and would the mayor care to come with him? It was as innocent as that.

The testimony from this hearing is great reading, and is full of stories of Van Wyck’s wide-eyed innocence in all of the dastardly doings in his city. He had no idea there was a monopoly, he did not know that the piers were closed to independent ice companies, and he had no idea that the price of ice had doubled, and that people could not afford it.

No clue whatsoever, your Honor. Being mayor meant delegating, and well, with all he had to get done in City Hall, he just had no clue. He thought Charles Morse was a fine man and a canny businessman. He was just gobsmacked.

Long story long, all of this attention and outrage caused Morse and AIC to back down. He lowered the price of ice, although it was still a third higher than it had been at the start.

There was no more talk of “shortages.” Boss Croker let his deputy John Carroll fall on his sword, and he was publicly let go. Van Wyck was disgraced, his political career over, and lost his bid for re-election.

Tammany Hall lost power for a couple of years as Fusion candidate and reformer Seth Low was able to take the mayor’s office in 1901. The New York Times would later say that the Van Wyck administration was one mired in “black ooze and slime.” The Great Ice Scandal seemed to be over.

So what happened to everyone? What happened to AIC, Morse, Van Wyck and the ice industry in general? I’ll wrap it up next time, as “It’s Nice to Be Ice” concludes.

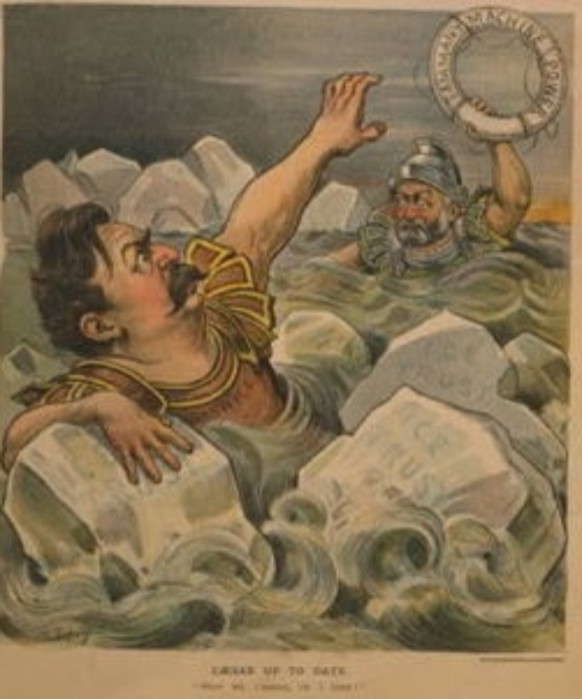

(Above: Cartoon published on the cover of Puck Magazine in 1900, depicting Mayor Van Wyck drowning in the American Ice Company Scandal. He’s being offered a lifeline by Tammany Hall.)

Wow, Van Wyck’s protestations of innocence and ignorance sound just like a press conference a certain governor gave this morning. Some stuff never changes!