Walkabout: Frear’s Troy Cash Bazaar, Part One

The late 19th century was the Golden Age of the department store.

1907 Postcard, Frear’s Troy Cash Bazaar, corner of Third Street and Fulton St.

Read Part 2 of this story.

The late 19th century was the Golden Age of the department store. In 1846, an Irish-born dry goods dealer named A.T. Stewart opened his Marble Palace in Lower Manhattan, the first department store in the United States. Up until that time, there had been retail shops selling every kind of goods imaginable, but Stewart was the first to combine different kinds of goods into one large store, making the phrase “one stop shopping” a reality. He knew his target market was women, and his store was set up to make the most of a woman’s shopping day. He staged fashion shows, and offered the finest in European fashions, as well as fabrics and other dry goods.

After the Civil War, the idea of the department store took off in cities and towns across the country. Most of the great store owners started out as dry goods men, selling fabrics that were used for clothing for the entire family, as well as cloth for draperies, upholstery, and any other use. They also sold notions like buttons and ribbons and trim. Dry goods stores also carried ready-to-wear clothing and accessories for men, women and children.

When these retailers realized the possibilities that large stores offered, they began carrying goods that complemented the dry goods, and soon were also carrying merchandise like shoes, hats, undergarments, accessories, perfumes and cosmetics, clothing for all occasions for men, women and children, and then home goods like furniture, silver, glassware, rugs, lighting, tabletop linens, laces, fine art, and even pianos and organs. Each kind of merchandise was a different department, and thus, the department store was born.

Brooklyn had many great department stores, but the two greatest were both on Fulton Street, and started within five years of each other. Weschler & Abraham was founded in 1865. They grew and expanded, and in 1893, became Abraham & Straus. The other was Frederick Loeser and Company, founded in 1860. Both grew from dry goods shops to occupy huge stores on Fulton Street, offering the best of merchandise and customer service to Brooklyn’s eager female shoppers.

Abraham & Straus’ store was typical of many of the fine emporiums of the late Victorian era. The upper selling floors opened up onto a large central atrium, accessed by a grand staircase, and later, elevators. One could stand by the railings and see all of the other floors, with all of their different departments, as well as the opulent ground floor. Light streamed in from above, through a large domed glass roof. It was quite the shopping experience. Of course, today, the building is still there, now Macy’s, but the floors have long been filled in, and the grand staircase is no more.

But it just so happens that this splendor was not exclusive to Brooklyn. Far to the north, up the Hudson River, the city of Troy was making a name for itself. The iron and steel industry, along with the expanding textile and garment industry and the city’s proximity to the Erie Canal, was making Troy a prosperous and cosmopolitan city. In 1865, the same year Weschler and Abraham opened their dry goods store, a man named William Henry Frear and his partner Sylvanus Haverly opened their own dry goods shop at 322 River Street in Troy’s growing downtown area.

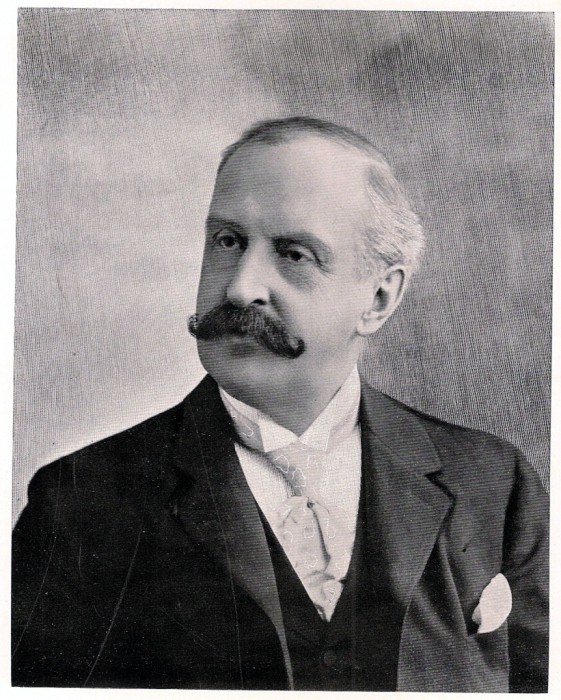

W. H. Frear was born in Coxsackie in 1841. As a young man, with college prospects at hand, he spent a summer working for a dry goods merchant in Coxsackie, an experience that changed his life and his vocation. He moved to Troy and worked for six years at John Flagg & Company, a successful dry goods merchant. Frear was eager to open his own store, and after saving those six years, and with capital from partner Slyvanus Haverly, and from his wife and parents, Haverly & Frear opened in 1865.

The venture was successful, so successful that they made over $100,000 that first year. That’s close to a million and a half dollars in today’s money. William’s old employer, John Flagg, was quite impressed with his pupil, and consolidated his business with theirs. The new operation, called Flagg, Haverley & Frear moved to two of the storefronts in Troy’s oldest commercial building, the Cannon Building, in 1868. The next year, Haverley pulled out of the enterprise, and the company was now Flagg & Frear. By March of 1874, Flagg’s interest had been bought out, and William Frear would spend the next 25 years as the sole owner and manager of his new store, called Frear’s Troy Cash Bazaar.

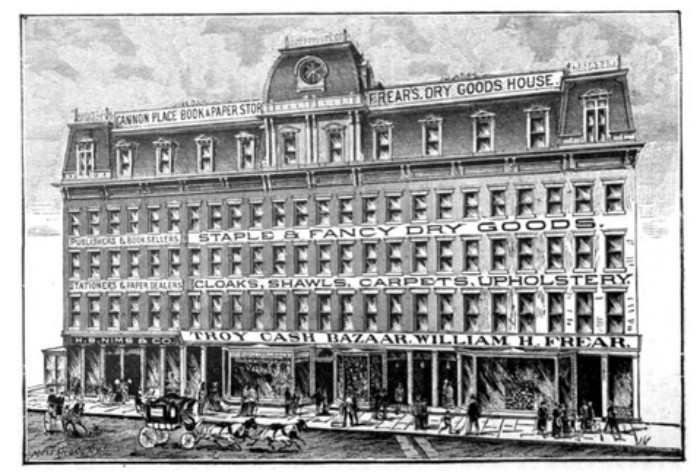

William Frear was a house afire. Frear’s Troy Cash Bazaar was his dream, and he went after it like a man possessed. The Cannon Building was Troy’s largest commercial building. It was designed in 1835 by the eminent architect Alexander Jackson Davis, with the building help of Ithiel Town. The building was four stories tall, and stretched across an entire block. After the Civil War and a couple of fires, the building got a new mansard roof in 1870, bringing it to five stories.

The Cannon Building had eight separate addresses, which spanned its 22 bays. When Flagg & Frear moved in, they took up two addresses; numbers 3 and 4 Cannon Place. In the years that followed, Frear’s Troy Cash Bazaar spread to the addresses next door, growing unit by unit. By 1886, he had taken over 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 Cannon Place – the entire building, and expanded to another annex around the corner. In 1891, he bought the Cannon Building.

During this time of unprecedented growth, the Bazaar was doing over a million dollars a year in business. The Troy Cash Bazaar was the largest department store in Upstate New York, larger than anything Albany, the state’s capital, had. Customers came from all over central and northern New York, and from Western Massachusetts and Vermont to shop. The store carried anything you could imagine, and boasted in advertisements in 1888 that it had 53 different departments, although some sources cite 55. You could buy ladies’ gloves, a carpet, furniture, underwear, and clothing for the entire family, fabric, silver services, toys, lighting, kitchen goods and much more.

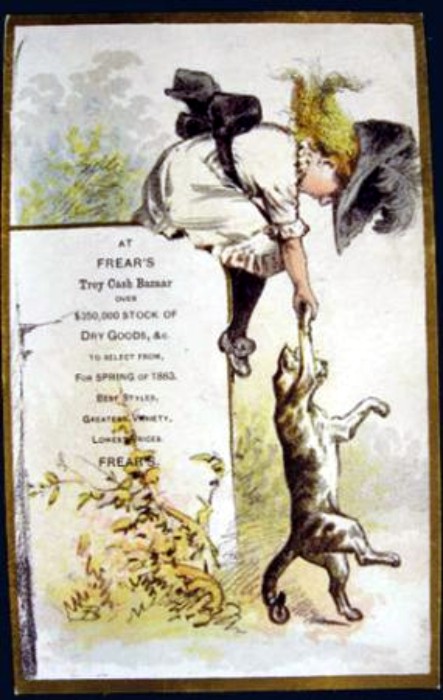

William Frear was the administrator, buyer and advertising wizard. He was known to show up to sell on the floor, and in the early days, was the bookkeeper, too. By 1886, he had from 250 to 300 employees bustling about, taking care of everything else. And there was a lot to take care of. Many people in the history of retail were great at growing their businesses, but Frear was inspired. He championed all kinds of advertising, and came up with innovations in promotion worthy of Madison Avenue. He was the first merchant to put a full page ad in a Troy newspaper. He instituted mail order and catalog services, and was the first retailer to offer delivery service, both local and further afield, in this part of the state.

Frear took as his business motto “Par negotiis ne que supra,” (Equal to his business, but not above it) and lived his life that way. He never seemed to be too tired or too busy to take on another project for his beloved store, or his beloved Troy. He was known far and wide as an honest and square dealer. His most important motto became a mantra in retailing that endures to this day. “Satisfaction guaranteed or your money cheerfully refunded.” Yes, Troy’s William H. Frear came up with this one, a motto that almost every retail business has adopted since he emblazoned it across his advertisements and in his store.

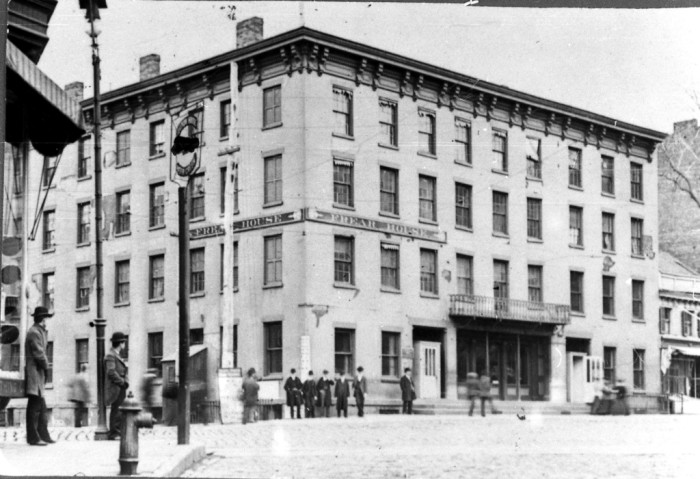

In 1878 Frear bought the American House Hotel, a large establishment located on the corner of Third Street and Fulton Street. He changed the name of the hotel to the Frear House. He also bought the lot across the street. By the 1890s, the Cannon Building was becoming too small for the still expanding business, and Frear wanted something new and grand to really show off one of the greatest retail emporiums in the state. In 1897, he tore down Frear House, and had a brand new store built in its footprint. It was going to be quite impressive and marvelous!

Far away in Chicago, the 1893 Worlds Columbian Exhibition had changed American architecture. This world’s fair introduced the wonders of electricity to an eager nation, and brought all kinds of technological innovations to the public’s attention. The fair also introduced into American society the City Beautiful and White Cities Movements. All of the major American buildings in the fair were made of white building materials – stone, stucco and paint, and all were of classical design, lit by thousands of electric lights. It was the “shining city on the hill,” an inspiration towards better things in an increasingly dingy industrialized world.

The philosophy behind the City Beautiful movement was that great civic and private architecture would inspire the masses to greatness in themselves. People in tenement slums could look to these wonders and work harder to be able to work or live in them, putting aside wretched poverty, and thus achieving the American Dream. It didn’t work out that way, but the nation got some great architecture. Gone were the dark brownstone and brick buildings, the new architecture would consist of Classical Greco-Roman inspired designs in white or light-colored building materials. This trend would fuel American urban architecture for the next 20 years and beyond.

William Frear, who always embraced the new, wanted one of these gleaming buildings for his new store, and in 1897, he got it, a beautiful marble clad structure built over a sturdy steel infrastructure, Troy’s first White Cities era building. It gleamed proudly on the corner of Third and Fulton, welcoming shoppers into the store, and into Troy’s ever expanding downtown shopping district. The marble façade of the building is covered with classical and Renaissance inspired carved ornament, including the intricately carved corbels supporting the upper story bay windows and the ornate cornice. There were ample display windows on the ground floor, and lots of natural light in the floors above. And inside – well, that’s where the magic was. GMAP

Next time: The conclusion of the story of William Frear and his Frear’s Troy Cash Bazaar. The inside of the store was more marvelous than the outside. And you could get just about anything! The 20th century would provide challenges, opportunity, death and rebirth for this great institution. But there is a happy ending here, so please join me on Tuesday for the rest of the story. The source material for this article comes from Don Rittner’s great article on the Bazaar in the Times Union (10.28.13), the Frear Park Conservancy, and Hoxie.com)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment