Walkabout: Death Rides the Rails, Part 2

Read Part 1 and Part 3 of this story. As any experienced train motorman will tell you, it’s not driving the train that’s hard, it’s making the stops. Brake too early, and the train stops before reaching the platform, and you have to lurch into the station. Brake too late, and you overshoot the platform…

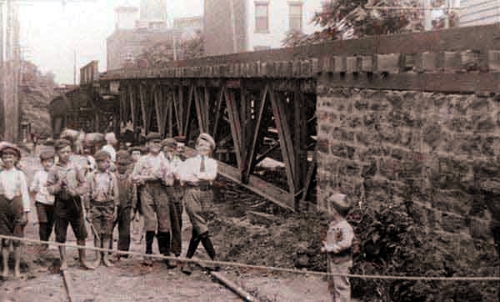

Brighton Elevated line, near Prospect Place. 1904. Photo via rapidtransit.net

Read Part 1 and Part 3 of this story.

As any experienced train motorman will tell you, it’s not driving the train that’s hard, it’s making the stops. Brake too early, and the train stops before reaching the platform, and you have to lurch into the station. Brake too late, and you overshoot the platform and have to back up. Go too fast, and brake too late, and you are in the perfect position for disaster. This was exactly what happened to an inexperienced motorman named Edward Luciano, as he approached the Malbone Street tunnel on the Brooklyn Rapid Transit line, at 6:42 pm, on November 1, 1918. What followed was the worst transit disaster in the history of the New York City subway system, a disaster so horrific that the name “Malbone Street” became too painful a reminder of the tragedy, and the street itself was re-named Empire Boulevard. We began the story in the last Walkabout. Here’s what happened that fateful day:

It was evening, and people were returning home to Brooklyn from a long day’s work. The five car train was full, its wooden cars holding at least a hundred or more people in each car. The BRT line was an elevated line, travelling along the old Brighton Beach tracks that still took people to the beaches and boardwalk of Coney Island in the summer. At its controls was twenty-three year old dispatcher Edward Luciano, in the middle of his second ten hour shift in a double shift day, on his very first day of being a motorman. The motorman’s union was on strike, and dispatchers like Luciano had been pressed into duty as motormen, even though most had no experience driving a train, other than the couple of hours in a rapid instructional practice session the day before.

According to experienced motormen who testified after the crash, the braking system on these cars was complicated; a combination of levers and moves that took finesse and experience. Much like an automobile driver feeling the right time to clutch and shift, an experienced motorman could feel the brakes as the train went into turns and down hills, and he knew how to handle whatever conditions were present. An experienced motorman would also have known the route. The Brighton Line had hills and valleys and sharp turns, as the tracks went from an elevated height to ground level, and occasionally underground, under the street, before coming up again. An experienced motorman, or even someone who was a frequent rider, would have known that there was a very steep hill and a sharp “S” shaped curve leading into the Malbone Street tunnel, as it passed under the intersection of Malbone Street, Flatbush and Ocean Avenues, where the Prospect Park Q line and the Franklin Shuttle run today. Locally, it was called “Dead Man’s Curve.”

But Edward Luciano was not a frequent rider of this line, and he was not an experienced motorman. He was a man pressed into duty, hoping to hold onto his job. The Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918 was raging through the city, and he was just recovering from its effects. One of his daughters had not been so strong, and had died the previous week, and the family was still deeply in shock and grief. The man should have been home in bed, or comforting his wife and children, but while World War I was still going on in Europe, this was a time when labor laws were not on the side of the working man. He had to be at work, to feed the remains of his family, no matter what.

Luciano made the Brighton run to Manhattan, turned around at Park Row, and headed back to Brooklyn with standing room only. He wasn’t the only one with little experience at his job. Track work in Brooklyn caused a mix-up with the switchmen, who sent him down the wrong tracks, heading east, instead of south-west. He had to back the train up, and get back on the right tracks. He was getting good at backing up, because he was still having trouble stopping at the stations, and often overshot them, and had to back up, which also took time. Now he was running late, so he decided to speed up and make up some time. No doubt, he had complaining commuters right behind him in the passenger section, adding pressure to an already stressful day.

As he headed towards the Malbone St. tunnel, at Park Place, the tracks made a sharp descent from the el track, around the “S” curve, and into a tunnel. Luciano picked up speed in the descent, and headed into the curve at over 40 mph. An experienced motorman would have braked on the hill, and taken the curve no faster than 6 mph. There were signs on the track warning motormen to slow down. As Luciano and the wooden cars entered the curve, he had tried to slow down, but couldn’t operate the brakes well enough, and then it was too late. Because of the strike, no one had checked the configuration of the cars in the train, either. Standard practice was to alternate heavier motor cars with trailer cars, which had no motors, and were therefore top heavy with passengers. Luciano’s train had not been checked, and right behind his motor car, two trailers had been coupled together, followed by two more motor cars. This would make a fatal difference.

As the lead car hit the curve, it lifted up off of the tracks, and scraped the roof, but being heavy, managed to stay upright. The first top heavy trailer car behind it was not so lucky and derailed, as did the one behind that one. The first car jackknifed across the tracks, hit the the tunnel, the side and roof torn wide open by the side of the tunnel, and came to rest across the tracks. The car behind that one, as well as the two cars at the rear, smashed through this car, stopping 200 yards down the tunnel. The third car was also sheared open by the force of the crash, spilling passengers out on to the tracks. The passengers in the last two cars were thrown to the floor and roughed up, but were basically unhurt. That was not the case of the people in the first cars. (If you don’t like descriptions of horrific death, don’t read the next paragraphs.)

It was worse than you could possibly imagine. The cars were old fashioned, even for 1918, and were made of wood. Iron and steel were used in the seat supports and the hand poles, as well as the train’s under carriage, but the cars had no steel supports on the sides or roof, they were flimsy wooden boxes with glass windows. The passengers in the jackknifed first car were all dead, cut to pieces or crushed in the initial crash, or by the other trains running over them. Many of the passengers in the second car were thrown out of the train, against the walls of the tunnel, as the car was cut open like a sardine can by the steel beams in the tunnel.

People who had been standing were instantly decapitated by the beams. Passengers were impaled by the metal poles , wooden splinters, and glass shards inside the train, and crushed under the debris and by each other. Some suffocated under the weight of other people or wreckage. Most of the people in that car also died. A very few missed death by inches, but were trapped by the crush of their fellow passengers, some pinned underneath dead bodies, or unable to move, trapped by deadly spears of metal and wood.

The survivors in the rear cars found themselves trapped in a dark tunnel surrounded by the dead, dying, and injured. They couldn’t get around the wreckage, and couldn’t see to help others or themselves. The screams of the injured and the hysterical filled the tunnel, and small fires only added to the hysteria.

When the train crashed, the sound was heard for miles around. The men in the police station house at Flatbush and Snyder Avenue could hear it, and reported to their superiors that an awful crash had taken place in Prospect Park. Neighbors clogged switchboards, reporting the crash. Because the wreck happened between stations, it took police and rescue teams over half an hour to coordinate an organized rescue. They had to press through the crowds of civilians that had already begun to gather, many of them people looking for family members.

They arrived at a war zone. There were bodies, and body parts, scattered everywhere in the tunnel, along with dazed and injured survivors. In the chaos of the wreck, the power on the third rail had gone out, thankfully. But then, someone at headquarters, thinking striking workers had sabotaged the rails, threw the switch, turning the third rail back on. Some of the injured and previously uninjured alike were electrocuted on the spot, shorting the system out again. It was hell. Rescuers couldn’t see, and cars were brought to the mouth of the tunnel, their headlights providing the only light for rescuers. It would take time to rescue the living, and remove the dead.

Bodies of men, women and children were carried out of the tunnel and lined up by the side of the street. They were carried to nearby police stations for identification, although that was not possible in many cases. The bodies were eventually transferred to the Kings County Morgue. The injured were taken to Kings County and other hospitals, and a temporary hospital was opened up in nearby Ebbets Field for those not severely wounded. By the morning, the streets were filled with thousands of people looking for relatives or friends, or coming to view the accident. Most of them walked.

The authorities immediately called for the motorman’s identity and his head. Astonishingly, he had walked away uninjured from the crash, and in a daze, had gone home, where he was arrested. He had no idea how he had gotten out of the crash, and couldn’t remember how he had gotten home. Edward Luciano lived at 100 33rd Street, and when questioned, thought he had taken a trolley home, but wasn’t sure. He was found sitting in a chair in his apartment, white as a sheet, and in shock. He was taken to the Snyder Street station house and questioned by the police, the district attorney, and Mayor John Hylan.

Hylan didn’t like the independent lines, like the BRT, anyway. He felt the entire transit system should be unified and under control of one agency, and not run by private companies with no oversight. This wreck was a total justification of his viewpoint, and he was on it, calling for a complete investigation of the railroad, its employees and officers, and how it did business. There would be a trial, not only of Edward Luciano, but also BRT executives, union men, and anyone else who was responsible for this crash. 93 people were dead, and over 250 injured, some quite severely. There would be a reckoning, and there would be retribution.

Next time: the conclusion of our story. The investigation and trials, the changes made to the system, and the fate of the BRT and the Malbone Tunnel.

Thanks MM – or maybe not. Whenever I read one of your great articles I then end up spending at least another hour of my workday reading more about what you wrote. Today I spent/wasted an hour learning that Malbone street was named for a Brooklyn Grocer/Real Estate developer that sold lots along what is now Empire Blvd.

My brain thanks you – my employer….not so much 🙂