Walkabout: Celebrating Thanksgiving

According to the stories we learned in elementary school, we’ve been celebrating Thanksgiving since 1621, when the Wampanoag people saved the Pilgrims from starving in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Since then, the pageantry of Thanksgiving has included white collared Pilgrims serving turkey, corn stuffing, mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie. Yes, the bounty of the harvest – food….

According to the stories we learned in elementary school, we’ve been celebrating Thanksgiving since 1621, when the Wampanoag people saved the Pilgrims from starving in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Since then, the pageantry of Thanksgiving has included white collared Pilgrims serving turkey, corn stuffing, mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie. Yes, the bounty of the harvest – food. Lots of food.

In the middle of the Civil War, in an effort to bring the country together at an especially demoralizing time, Abraham Lincoln encouraged Congress to declare a national day of thanksgiving for the nation. In 1863, they made it official, and the last Thursday of November would from that time be Thanksgiving Day in the United States. (In 1941, FDR signed the law that made Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday in November, instead of the last Thursday.) It was thought that this would be a day of religious observance, a day to give thanks to God for all of His blessings. But immediately, it was co-opted by the food.

When it comes down to it, Thanksgiving in Brooklyn in the late 1800’s really wasn’t very much different than it is today. Take away today’s technology, and both share a celebration where giving to others, family, food and sports still are the most important parts of the day. The Brooklyn Eagle said in their Thanksgiving editorial of 1897, “The day is crowded with religious, social and sporting events, open to everyone in addition to the family reunions that are the main features of a Thanksgiving.”

The editorial went on to say, “The ancient reverence for, and observations of the day that inspired the forefathers, coupled with the advantages offered by modern civilization for enjoyment and amusement have made it one of the most highly regarded of the holidays, and every man or woman whose services are not vitally necessary to public safety, convenience and comfort, will be relieved from toil and be at liberty to find in their churches, in the fields, on the waters, or the cycle path, the interests which go to make up his or her holiday.”

Of course, food was the major part of Thanksgiving Day festivities. The newspapers were full of recipes, advertisements and opinions on, or about the proper dishes to serve, and the preparations thereof. The demand for the quality of the foodstuffs was as high as it is now. In 1902, in an article about the perfect turkey, poultry vendors at the Wallabout Market said, “Certainly, they [the wholesale vendors] will not buy the scalawag, unconditional turkey, which in the past constituted much of the shipments deigned for Thanksgiving consumption.”

Grocery stores also had large sales campaigns, as did chocolatiers and bakeries. There were also plenty of advertisements for sales on all of the necessary goods for setting the table: china, silverware, glassware, table linens, and of course, furniture and lighting. Modern Madison Avenue did not invent The Big Holiday Sale. The Victorians did, big time.

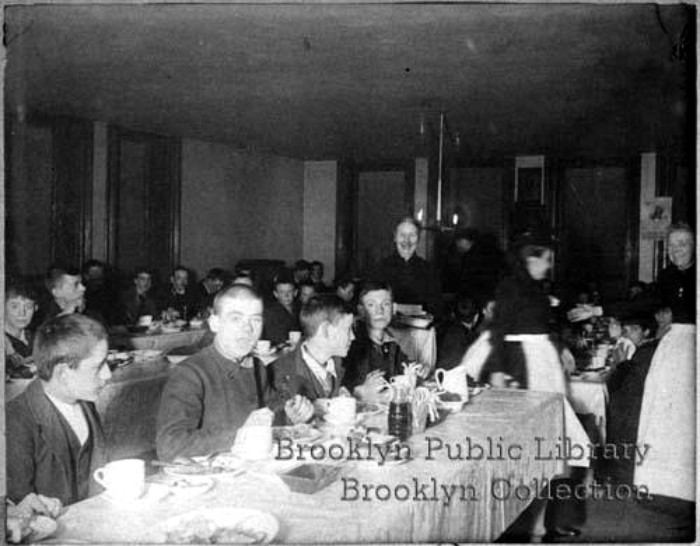

In 1902, the Brooklyn Eagle wrote: “Thanksgiving was a reality in Brooklyn Borough yesterday. It was in no way perfunctory. Everybody was happy. The poor, worthy or unworthy; the sick and the distressed; the criminals and those accused of crime who are prisoners in the penitentiary, jails and police stations were fed in a generous manner, and there was no occasion last night for any to go hungry to bed. At all the charitable institutions, bountiful repasts were served. The homeless children who are cared for at the Brooklyn Industrial Scholl and of the various homes were abundantly provided for and were given license to eat without stint. As one little chap expressed it: ‘Why, we kin eat more’n we want: we kin stuff!’”

Thanksgiving was a time for charity. Hundreds of articles in the Eagle over the years highlighted different charitable organizations’ work feeding a Thanksgiving meal to everyone from orphans to prisoners to those in hospitals and insane asylums. Each year, one organization always fed the newsboys, mostly orphans, who worked for pennies under harsh conditions, selling papers. The Sands Street YMCA, which ministered to the Navy Yard held a special Thanksgiving dinner for sailors far from home. The best of the generous spirit of Brooklyn came out at the holidays.

Of course Thanksgiving would not be complete without sports. Each Thanksgiving in the last decades of the 19th century saw more and more sporting events on that day. In 1897, Thanksgiving Day saw several college and private athletic clubs play football, there were several places to shoot, including clay birds at the Crescent Athletic Club in Bay Ridge, and live birds at the Brooklyn Gun Club.

One could be in a bicycle race sponsored by the Windsor Terrace Wheelmen, play golf at the Crescent, do a cross country race in the park, or attend the dog show at the old 13th Regiment Armory, at Fulton and Flatbush. If your religion was not sports, and was actually religion, almost every church in Brooklyn had special services, with concerts, soloists and special speakers. For many Brooklynites, Thanksgiving Day started at church, and ended with a large meal, and a glass of brandy in the parlor.

And then there was one tradition that did not carry into the present. It was called “Fantastics”. Young men, and it was mostly young men, would dress up in fantastic and ridiculous costumes, often consisting of their sisters’ or mother’s clothes, and go from door to door and beg for candy, apples and sweets. Like trick or treating, groups of teens would go from door to door trying to get as much spoils as possible, before going to their own homes to eat.

The Eagle describes the Fantastics, as practiced in 1896, already noting that the practice seemed to be dying out: “Early in the morning, dressed in all sorts of odd apparel, with coats and trousers turned inside out, some arrayed in their sisters’ and even their mothers’ clothes, the youngsters form in procession and march up and down the streets, blowing the unearthly tin horns and making noise enough to wake the dead. This is a sort of preliminary programme. The real fun comes in the ringing of doorbells and soliciting gifts.” Another Eagle writer penned a poem about the Fantastics, saying in part:

Ted purchased from the corner store,

A mask with crimson cheeks and nose,

And donning this, he filched and wore,

A dress that once belonged to Rose;

Then with a basket and a horn,

He sped away to meet the boys;

And thus commenced at break of dawn,

The ragamuffin’s fun and noise,

To usher in Thanksgiving Day.

Grotesque they looked and weird indeed,

With sweeping skirts, false frizzed, basque

A tomahawk to urge their need,

And whiskers trimming all their masks:

And in the leader’s rough red hand,

A parasol of lightest blue,

And close behind, the queerest band,

I ever saw, or ever you.

To usher in Thanksgiving Day.

The more things change, the more they remain the same! Happy Thanksgiving, everyone. Walkabout will return next Tuesday.

(Newsboys being served Thanksgiving dinner at the Newsboy’s Home on Poplar Street in Brooklyn Heights. 1892. Photograph: Brooklyn Public Library)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment