Walkabout: Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers, Part One

Read Part 2 of this story. Public transportation in Brooklyn began with stage coaches, called omnibuses. They ran along the major streets, and had fixed routes. They began running around 1827, and helped expand the borders of the bustling town of Brooklyn by taking passengers outwards away from the harbor and Heights. They were pretty…

Read Part 2 of this story.

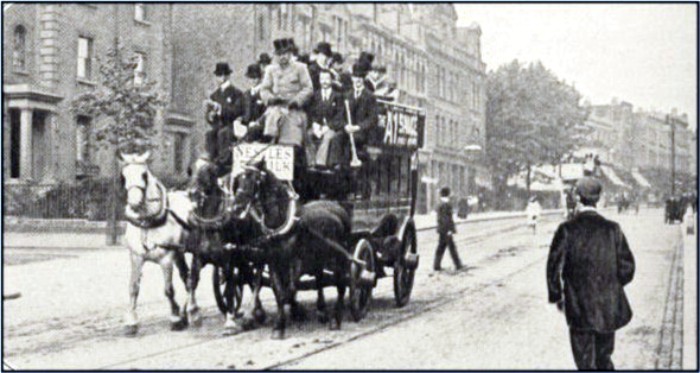

Public transportation in Brooklyn began with stage coaches, called omnibuses. They ran along the major streets, and had fixed routes. They began running around 1827, and helped expand the borders of the bustling town of Brooklyn by taking passengers outwards away from the harbor and Heights. They were pretty reliable, but small. The average omnibus could only hold 15 passengers, and that’s with several of them hanging on to the sides and riding on top or with the driver. A passenger would signal the driver to stop by pulling a cord which was attached to the driver’s leg. Could this be one of the origins of the phrase “pulling my leg?”

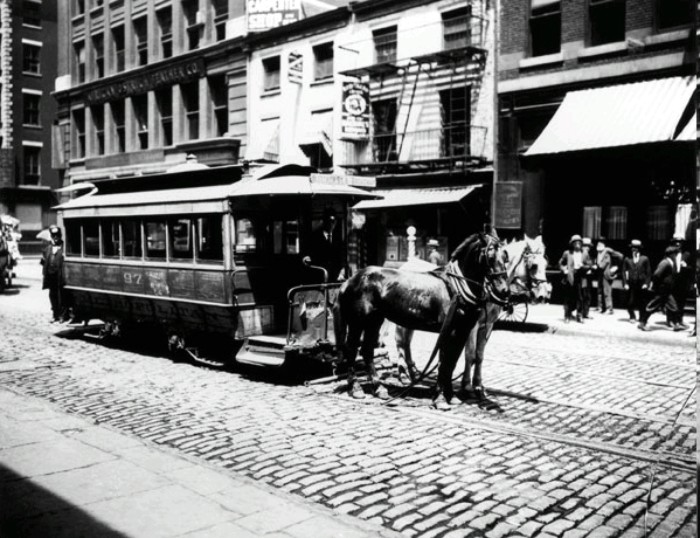

As demand for better and larger forms of public transportation, other than trains, grew, the horse drawn trolley cars were developed. Some bright entrepreneur looked at a railroad car, the track, and the poor horse, and put them all together: enter the horsecar.

Brooklyn’s network of horsecars began in 1854. They were already running over in Manhattan, and had been since 1832. Since the cars ran on metal wheels along a fixed track, and not bumpy cobblestone streets or muddy side streets, it was much easier for the horse to pull a larger load. This was a great improvement over the omnibuses.

There were limitations, of course. The horses were still pulling heavy loads, and most only lasted about five years before they were done and broken. They needed a lot of food and water to fuel them, and so added to the pollution on the streets and had to be cleaned up after. And they were slow – at best clopping along at a human’s fast walk. Still, they allowed people to commute from places like the town of Bedford, in Central Brooklyn, for example, to the ferry in a reasonable time. This created a commuter class that could live further and further away from Brooklyn Heights and downtown, and still work in Lower Manhattan.

After the Civil War, inventors came up with cable cars. They ran on a track with a cable that ran constantly underground, much like a funhouse ride in an amusement park. Since there were no horses involved, the cars could be larger and heavier, and hold more people. The car had an engineer who stopped the car by detaching it from the cable and applying the brakes. When first introduced, the cable car seemed like the greatest thing ever, but cities soon found them to be very expensive to build, maintain and run.

They were also dangerous. Since the speed was constant, unless the car was off the cable, going around sharp corners was quite scary and many accidents occurred, with serious injuries and fatalities. They were never fully implemented in Brooklyn, and only ran in a few places, the most famous and useful being across the new Brooklyn Bridge, after 1883. For many years, a cable car carried passengers across the bridge to Manhattan and back. Passengers then disembarked and caught horsecars or surface trains to their destinations.

There was also a cable car carrying passengers along Montague Street down to the Wall Street Ferry. The hill leading down to the ferry was very steep, and more than one accident happened on this line. The most serious happened in 1892 when a hansom cab driver ambling along on the tracks in front of the cable car refused to move out of the way, which caused the engineer to brake all the way down the hill. The cable snapped, and the car rolled down the hill and crashed into a barrier placed there for that purpose. The engineer was seriously hurt, and his six passengers were tossed out of their seats. The cab driver was arrested.

Cable cars were not going to work as a mass transit surface method. It wasn’t until the late 1880s that technology and mechanics came together in the form of the electric powered street car. This changed everything. By 1890, Brooklyn got its first electric powered street car. It was, fittingly, on the Coney Island Line, which took day trippers to the sea and the resorts of Coney Island, years before the amusement parks were built. Soon other lines were developed, all privately owned. Brooklyn had at least fourteen separate companies running street cars in the late 1800s, early 1900s. These cars ran along hundreds of miles of streets in every neighborhood in Brooklyn.

These companies divvied up the city, and most concentrated on their own separate sections, while running one or more lines that travelled to the Downtown/Brooklyn Bridge/Brooklyn Heights area. Someone could leave their home in a remote part of Brooklyn, take several different lines owned by several different companies, in order to reach the shopping district Downtown. The crisscrossing electrical lines running above most streets must have been quite thick in some places. It was a marvel of what was at the time, cutting edge mass transit technology.

As the 20th century progressed, the subway lines were built and introduced, taking traffic away from the street cars. But depending on where you lived, the street car was often necessary to use to get to the subway. Plus it often went places the subway did not go, or got you there quicker, so trolleys, as they began to be called, were quite popular well into the first half of the 20th century. I’m sure horses everywhere were overjoyed. Incidentally, the word “trolley” comes from the trawler, the pick-up wand that projects upward from the car, and rides on the cables, conducting electricity to the motors.

Everyone loved the trolley. Brooklyn’s beloved baseball team, the Trolley Dodgers, later just the Dodgers, got their name because the ballpark they used in East New York was near Broadway Junction, where many different trolley lines crossed. One had to be swift and agile to run across the street in that neighborhood, much like a ball player running the bases. It was a good name, and quintessential working class Brooklyn.

But the trolley was not a perfect transportation device. They had a lot of accidents. As far back as 1893, the Brooklyn Eagle ran an editorial urging the mayor, other politicians and city officials to take a hard look at the safety of the streetcars. There had been a lot of crashes, and many injuries and even deaths. People slipped while riding or exiting and fell beneath the wheels, the cars ran into horse drawn wagons, or vice versa, or the cars hit people in the streets. The trolley cars were great, but they were also dangerous weapons.

The Eagle said, “There is absolute safety and there is a comparative safety. The former is beyond reach. Anyone who moves from place to place, even if he always walks, is in danger of being struck by a falling tree or a brick from a chimney. Comparative safety is believed to advance with the introduction of traveling improvements. It is a familiar fact that the transportation by the old stage coach or by horseback killed or injured more people proportionately than the mile-a-minute locomotive. There have been shocking trolley casualties, but there have been more on the horse roads.” The editorial went on to urge public officials to champion the trolley, but also make sure that it was as safe as possible.

By the 1920s, many of Brooklyn’s trolley lines were forty years old. But now they were no longer sharing the streets with horse drawn carriages and wagons. The automobile, which began rolling down Brooklyn’s streets as early as 1895, had taken over the imagination of the middle class New Yorker, and the cars were taking over the streets, as well.

Once the toy of only the rich, the automobile was now being mass produced by dozens of car companies, with hundreds of models. A middle class family could afford a new car, and even those of lesser means might be able to swing a used vehicle. Brooklyn’s Automobile Row, on Bedford Avenue and surrounding streets, had dealerships carrying every kind of car and truck imaginable. Trolley cars had to share the road, and drivers were not happy.

Streets were teeming with street traffic. In the midst of that, the trolley cars were taking up the center of the street, slowing traffic down. The aging track systems needed maintenance, as did the cables above. Since the companies were still privately owned, repairs by the companies started to get further complicated by the city demanding that the trolley companies also fix sidewalks and streets. The cities upped their charges to the carriers but the trolley companies could not pass their expenses along to commuters. Trolleys were mandated to only charge a nickel for a fare, and many began to go out of business. Champions of the car, like Robert Moses, couldn’t be happier.

Next: By the 1930s, many of the trolley lines began to be replaced by buses. But some trolley lines continued until the 1950s. More on the Brooklyn trolley next time.

(Postcard: Williamsburg Plaza trolley cars, 1907)

Great post Montrose! I blogged about the 1895 trolley strike on the Brooklyn Historical Society blog last year. Check it out at: http://brooklynhistory.org/blog/2014/08/25/the-great-trolley-strike-of-1895-part-1/

The third photograph down from the top that is labeled below as “Brooklyn horsecar. Photo: Brooklynhistory.com” is not from Brooklyn. Apparently “Brooklynhistory.com” has made an error. In fact it is a fairly well-known photograph of what is supposed to be the last horse-drawn streetcar line in New York City. It is definitely on Bleeker Street just east of the main New York University building. The taller building located directly above the center of the streetcar still exists and is recognizable from this photograph.