Walkabout: Brooklyn and the Erie Canal

Read Part 2 of this story. If you grew up in New York State, as I did, at some point, your public school education included the history of the state. I grew up far upstate, in Otsego County, and we had New York history in seventh grade. I always found state history fascinating, as from…

Read Part 2 of this story.

If you grew up in New York State, as I did, at some point, your public school education included the history of the state. I grew up far upstate, in Otsego County, and we had New York history in seventh grade. I always found state history fascinating, as from where I was, one could actually go to the places where many historical events happened and stand on the ground where battles took place that shaped the state and the nation, or visit the homes where great people shaped great ideas. Of course that can happen in New York City, or anywhere else, but we had the entire Empire State to choose from, from Ticonderoga to Buffalo.

On a more intimate scale, we could look around at the small towns we lived in, and trace the origins of the people who first settled there, who they were, and why they built the towns as they did. Were they crossroads towns or village squares? Why did some small towns prosper and others stagnate? Since not much changes upstate, not even in 250 years, sometimes these towns were a time capsule, often with the descendants of the original settlers still in the homes of their ancestors. My love of history and architecture was born there, and still lives, whether in Brooklyn, Troy, or back in Gilbertsville, where I grew up.

The creation of the Erie Canal, which has its origins only a couple of miles from where I now sit, was one of those New York State defining moments. It is the reason we are called the “Empire State,” and although it cuts across the state far north of New York City, it is also one of the reasons New York City is one of the great port cities of the world, and a financial hub for the state and nation. Goods that made their way down the Erie Canal to Brooklyn’s own ports made fortunes for Brooklyn’s merchants, ship owners and manufacturers. The materials of many Brooklyn’s homes came down the canal, and you cannot fully tell the history of Brooklyn without mentioning the Erie Canal.

A canal cutting across the state was proposed as early as 1768, before the Revolutionary War. This canal was proposed to connect the Hudson River to Lake Ontario, at Oswego, but the idea didn’t get too far, and the war put all plans on hold. After the war, in 1808, the canal came up again, as the new nation looked for ways to grow. This time it was proposed as a connector between the Hudson and Lake Erie, further south and west.

The canal would run along the Mohawk River, a tributary of the Hudson River, the only east-west running river cutting through the gap between the Catskill and Adirondack mountain ranges. It would connect the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, opening up the country to settlement, and enabling massive amounts of goods to flow to the interior of the country. In 1808, Governor DeWitt Clinton finally was able to get federal funding for what his detractors called “Clinton’s Ditch,” and construction of the canal began. Even Thomas Jefferson, who was president at the time, thought the idea an impossible folly.

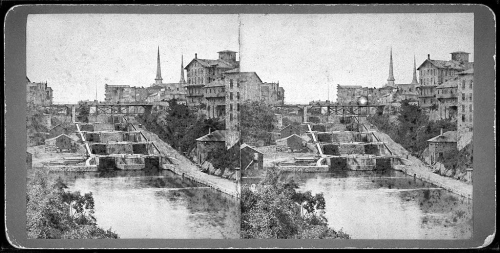

And for good reason. Although the Mohawk River provided a great foundation to build on, the canal needed to run for 363 miles, across wilderness, forests, swamps, mountains and valleys. The land between Albany and Buffalo rose almost 600 feet, so locks would have to be built to raise or lower the canal boats as they progressed along the canal. The technology of the time allowed for only 12-foot locks, so over 50 of them needed to be built, and the river dredged and widened where needed. It was a massive engineering project which would cost $7 million dollars at the time, a number almost unheard of. As a comparison, the United States, only a few years before, in 1803, paid approximately $15 million for the Louisiana Purchase, which gave us 823,000 acres of land, stretching from New Orleans to Canada. This was half as much money for only 363 miles.

But once approved by the state legislature, the project proceeded, and the first leg of the canal, between Utica and Rome, began in 1817. It took two years to go 15 miles, and they finished in 1819. At this rate, it would take 30 years to finish the canal. Some new technology and innovation would have to be learned or invented, or this project would never be finished. And it was.

Since there were no civil engineers in the fledgling United States, the men who engineered the canal learned on the job. James Geddes and Benjamin Wright laid out the route. They were judges who had handled land disputes before taking on this project. Geddes had only hours to learn how to use surveying instruments. A mathematician named Nathan Roberts was on the team, as was a 27-year-old amateur engineer named Canvass Wright, who persuaded Governor Clinton to let him go to England and learn from the canal builders there, and bring back what he had learned.

The men who built the canal had to tear out virgin forest and excavate tons of earth. They had to build aqueducts to divert the river water, and cut through limestone mountains and malaria-ridden swamps. As the sections of canal proceeded, new techniques were devised to make tree and stump pulling easier, and earth removal more efficient. American engineering grew in leaps and bounds in innovative, on-the-job invention. The labor was provided by a large Scots Irish immigration to New York, adding to the thousands of others who labored and died to build the canal. Over 1,000 workers died in the swamps at Cayuga Lake, near Syracuse, when malaria-carrying mosquitoes infected the massive work force.

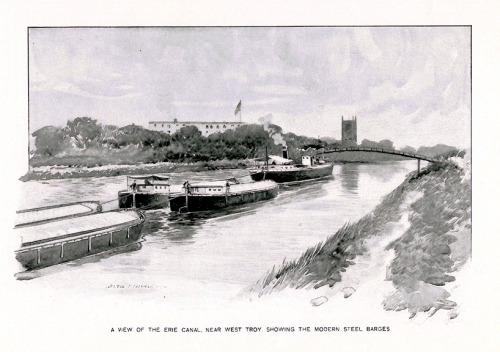

The canal was cut 40 feet wide and 4 feet deep. The earth from the dredging was piled up on the downhill side, forming a walkway called the towpath. The canal boats were pulled by horses and mules from a towline, both east and westbound boats from the same side. The drivers, called “hoggees,” devised an elaborate system for allowing boats to pass when they met. One line would go slack to allow the other boat to pass over it, as the boat steered to the other side of the canal. It was simple, but efficient.

As each section of the canal was finished, it was opened for traffic. The last sections to be completed involved crossing the Niagara Escarpment near Lake Erie, an 80-foot wall of dolomite limestone, which involved the most complicated sets of locks and channels to raise the boats over 60 feet over the course of two sets of five 12-foot locks, giving rise to the town of Lockport. The choice of the town of Buffalo over its neighbor, Black Rock, as the terminus of the canal ensured Buffalo’s rise as one of the great cities of New York State.

On the eastern side, the Albany/Cohoes/Troy area was the terminus of the eastern end of the canal. In 1825, the canal was completed, and a huge celebration took place, with a 90-minute cannon salute from Buffalo to New York City. A flotilla of boats, led by Governor DeWitt Clinton’s Seneca Chief, sailed the length of the route from Buffalo across the canal to Albany and down the Hudson to New York City, a journey of ten days. Clinton ceremoniously poured water from Lake Erie into New York Harbor to celebrate the “wedding of the waters.” On the return trip, water from the Atlantic Ocean was poured into Lake Erie in Buffalo. The canal now was open for business.

OK, so where’s Brooklyn in all this? The importance of the Erie Canal to New York City, and specifically Brooklyn, that’s in Part 2.

Top photo: Mural of Governor DeWitt Clinton and the Marriage of the Waters in New York Harbor by C.Y. Turner in 1905. The mural is at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx.

Luckily my education about the Erie Canal also included singing My Gal Sal, as transcribed by the delightful Pete. We had to end the class by singing it. Still and all, great and fascinating part of NY history- looking forward to the next part, MM.