Walkabout: Booker T. Washington and Brooklyn, Part 1

Read Part 2 of this story. For many, both black and white, Booker Taliaferro Washington was the most famous black man in America between 1890 and 1915. He was seen as the voice of the Negro in the United States during that time; the leader of a group of Americans who found themselves free, after…

Read Part 2 of this story.

For many, both black and white, Booker Taliaferro Washington was the most famous black man in America between 1890 and 1915. He was seen as the voice of the Negro in the United States during that time; the leader of a group of Americans who found themselves free, after centuries of slavery, but generally without power, social standing, or equal opportunity to achieve the American dream at the turn of the 20th century.

He became a controversial figure throughout the rest of the century, but love him, hate him, or know nothing about him, Washington was one of the most influential men in the history of this country. His travels often took him to Brooklyn and New York City, and that part of his story, as well as a look at life for African Americans in Brooklyn at that time, will be presented here.

First some background: Booker T. Washington was born into slavery in 1856. He was the child of an enslaved mother named Jane, and a white plantation owner from another plantation in rural Virginia. After the Civil War, young Booker and his mother moved to West Virginia, where his mother married his stepfather, Washington Ferguson. Booker took his stepfather’s name as his own surname, out of respect for his new parent.

The family was poor, but Booker was able to get some schooling while working in the coal mines and salt furnaces of West Virginia. He walked 500 miles from his home, a state away, to southern Virginia to attend Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, the famous school established for freemen, today called Hampton University. He couldn’t afford tuition, but worked as a janitor at the school in order to attend.

The white founder and president of Hampton, General Samuel C. Armstrong, had led a Negro regiment during the Civil War, and he was committed to African-American education. He found a like mind in young Booker T. Washington, and became his friend and mentor. Washington graduated in 1875, and went back to West Virginia to teach in his old home town. He got married in 1881, to the former Fanny Smith, and was then offered a teaching job back at Hampton. He accepted, and was in the right place at the right time when the new Tuskegee school was founded.

In 1881, the Alabama legislature approved a $2,000 expenditure to start a “colored school” at Tuskegee. It would be called the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, today Tuskegee University. They asked General Armstrong to recommend a white man to lead the school.

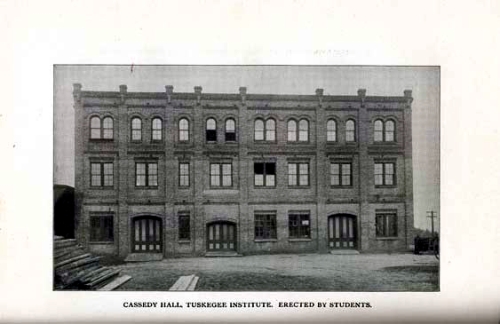

He gave them the 25-year-old Booker T. Washington. The first classes were held in a church. Washington bought a nearby plantation, and over the course of the next few years, the students and faculty themselves built the school, making the bricks themselves, building the buildings, tending fields and growing crops. It was both a teaching situation and a necessity.

Washington would spend the rest of his life at Tuskegee. He immediately went on fund-raising tours, giving lectures on the merits of donating to the school. Both men and women attended Tuskegee, and both were expected to take not only academic courses, but vocational courses, learning carpentry, masonry, farming, cooking and other craft and domestic skills. His was the last generation of African-Americans born into slavery, and Washington believed that the way to Negro equality in post-Reconstruction Southern America was through “industry, thrift, intelligence and property.”

While life for African Americans in the North was hardly a bed of roses, black life in the South was so much worse. The Civil War may have freed the slaves, but not much else changed. Reconstruction was a total failure, and after the Northern carpetbaggers left, life went back to what it had been before in terms of black-white relations.

The vast majority of the black population was still working the land, now as sharecroppers instead of slaves, but the social inequality remained. Blacks could not vote, had little or no political or social power, few opportunities for education or advancement, and Jim Crow segregation laws, and threats of “swift justice” by hate groups like the Klan were everywhere.

Black leaders in the South, as exemplified by Booker T. Washington, struggled with advancing the opportunities for true citizenship for the race while placating the white establishment. It was a fine line to walk.

In 1895, at the Cotton States and International Exhibition in Atlanta, Washington gave his famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech, which made him a national figure and catapulted him into a leadership role in black America. In that speech, Washington encouraged white Southerners to welcome black workers, saying that the South was where the Negro could be given a chance, instead of in the North, where immigrant workers were overwhelming the marketplace.

He set forth the terms of the Compromise: black people would accept segregation and social inequality, if the white establishment would do their part to provide education and due process under the law. He praised the African American community for its loyalty to whites and their eager service, but warned that the South’s current oppression was straining that loyalty, and that black people looked to Southern whites to provide fair treatment.

He stated that jobs and employment were more important than social rights, saying that “the opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house.” Washington felt that segregation was acceptable, if both black and white societies could work together like separate fingers in a hand.

Needless to say, this stance proved immensely popular with his audience, and resonated well with businessmen, politicians and white audiences across the South and in the North as well. A patient, long suffering and eager workforce of black laborers who accepted their inferior social status and didn’t cause trouble or make waves was certainly worth a few segregated schools and places like Tuskegee, which would train generations of skilled workers.

They were on board, and hailed Washington as the leader of his people, and his career as a successful fundraiser, lecturer and social commentator took off. He would spend most of the rest of his life crossing the country delivering this message. Brooklyn, as well as New York City, was very often on his lecture itinerary.

Washington had the support of many black educators, businessmen and clergy, a base from which he formed a national coalition. He was important to black politics, and had the support of many black communities across the country, as well as firm support by many wealthy liberal whites, especially here in the North.

He would have access to some of the most important halls of power, including the White House. He was greatly supported by New York’s Republican Party, and was invited to the homes, clubs and pulpits of the city’s liberal and business elite. This support made him a frequent speaker here in Brooklyn, lecturing in many of her largest churches, lecture halls and clubs.

Starting in 1890, Booker T. Washington’s name started appearing in the Brooklyn Eagle. He was already getting a good reputation in stories about the establishment of the Tuskegee Normal School. Brooklyn was very interested in solutions to its own relationship with its African American population.

Although not sharecroppers or farmers, Brooklyn’s black population had its own issues with inequality, poor educational prospects, poverty, and lack of jobs or job advancement. The huge influx of immigrant labor also was problematic to black advancement, as racism proved more powerful than cultural xenophobia. Everyone was interested in what Dr. Washington had to say.

Next time: Booker T. and Brooklyn continues. Washington speaks at the Union League Club, meets with more than one President, and encounters opposition by the newly founded NAACP, and its eloquent leader, W.E.B. DuBois. He also finds out that walking while black can be just as dangerous in New York City as in a small town in Alabama. (Above photo: nndb.com)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment