Walkabout: A Honking Good Idea -- E.A. Laboratories, Part 1

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this story. If you’ve ever been walking down the street and a car passes you blasting the horn with the strains of “La Cucaracha,” “The Godfather Theme,” “Here Comes the Bride,” or some other popular eight bars of music making it past your earbuds, then you owe a…

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this story.

If you’ve ever been walking down the street and a car passes you blasting the horn with the strains of “La Cucaracha,” “The Godfather Theme,” “Here Comes the Bride,” or some other popular eight bars of music making it past your earbuds, then you owe a thought, or a good curse, to Emanuel Aufiero.

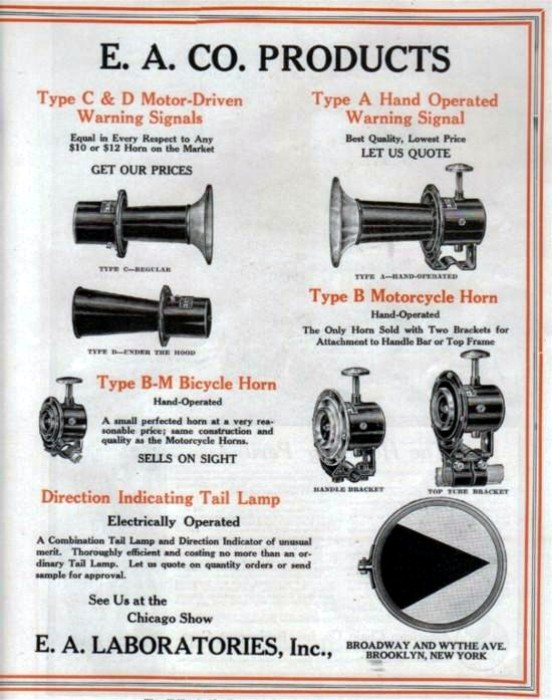

In 1908, he invented the first electronically operated motor horn. That one merely honked. His company, E.A. Laboratories, located right here in northern Bedford Stuyvesant, was where the first theme-song car horn was born. That didn’t happen in the 1960s or ‘70s either. It was back in 1941, during World War II.

Emanuel Aufiero was born in Italy in 1882. He and his brother Michael came to America in 1900 to seek their fortunes. Both brothers were mechanically inclined, but Emanuel was an inventive mechanical genius.

He was one of those people who could look at a piece of machinery and understand it, put it to good use, and fix it if it were broken. More importantly, he could see where that object, or tool or process could be improved. He was one of those idea men who could take something that already worked and evolve that object, taking it to the next step in its evolution.

At the dawn of the 20th century, there was nothing so intriguing and exciting as the ever-changing world of the automobile. It captured the 20th century imagination, and inventors and innovators were constantly evolving the motor car into something more efficient and better each year. The Aufieros got into the car accessory business.

Starting in a small workroom in Manhattan, Emanuel invented the first motor driven automobile horn. It was a variation on the classic “ahooga” horn that you’ve probably seen in old movies or at vintage auto shows. It was an instant success, and helped promote Mr. Aufiero into auto history, and soon, into his first law suit.

In 1910, Aufiero had ideas for car horns, windshield wipers, mirrors, signaling lights and many other small components that had big impacts on driving safety and automobile design. But he didn’t have the money to translate these ideas into reality.

That year, he went into contract with the Automobile Supply Company of Brooklyn, the largest producer of automobile accessories. Mr. Louis Rubes was president of the company. He eagerly took everything Aufiero came up with and went into production.

Aufiero was offered contracts that paid him a nice sum, but also prohibited him from selling any of his inventions anywhere else, or from producing them himself. Rubes also had the patent rights to the inventions and the rights to any future inventions, improvements or innovations to those products in perpetuity. Methinks Emanuel Aufiero either had a really bad lawyer, or no lawyer advising him when he signed over his rights.

During the years between 1910 and 1914, Aufiero continued to come up with new ideas for horns, especially, as well as other devices. He applied for dozens of patents, all of which he had to turn over to Automobile Supply. He began to chafe under the yoke of his contract. Other manufacturers had come to him asking him to design for them, but he had to turn them down.

Finally, in 1914, he and his brother Michael founded the E. A. Laboratories. His brother was president, and his sister-in-law, Michael’s wife, was also a named partner. The new company began production of a new horn, one that he had never shown to Rubes. A new patent was applied for, and this one had Michael’s name on it, not Emanuel’s.

When Rubes found out about it, he sued. He claimed that the horn was Emanuel’s work, not Michael’s, and therefore the property of Automobile Supply. He also claimed that he had put out hundreds of thousands of dollars producing Aufiero’s designs, and needed those designs to continue, or he would be out of business. The law suit covered 22 different patents, and had generated a 455 page complaint, the largest number of pages in New York State Supreme Court to that date. The case dragged on through 1916.

In 1915, Rubes probably poisoned the jury pool when he announced that because of the ongoing litigation, he was moving out of Brooklyn, and taking his plant to New Jersey. The company was pretty big, filling two large factory buildings on Taaffe Place in Wallabout. They made 85% of the bulb horns used on motor vehicles in the United States, and employed over 500 people, mostly men. Rubes had just found out he had lost a similar suit, this one filed by a company in Newark, and had to stop manufacturing one of his most popular horns. He really needed to win this one.

When the trial was finally ready to proceed in late October of 1916, Louis Rubes got sick, so sick he couldn’t testify in court. The judge, James C. Cropsey, was tired by this point, and decided to take the trial to Rubes. He had court convene at Rubes bedside at his home at 335 Jefferson Avenue. (Only a few doors down from my old Bed Stuy home, coincidentally). Judge Cropsey sat at the foot of Rubes’ bed, with the lawyers for both sides in attendance and the court reporter. Louis Rubes testified from there.

I tried to find a story on the result, but couldn’t. A decision may not have been made. Louis Rubes filed for bankruptcy in 1917. The legal costs and the injunctions against manufacturing the items he lost in the other case, and the possibility of losing the Aufiero patents was too much for his health and finances. He had to liquidate everything. He moved out of his house, to a house on Revere Place in Crown Heights North, and “retired.” He died nine years later of pneumonia, in 1926. He was only 57.

With many of his patents once again in his control, Emanuel Aufiero and his brother continued to grow their new business. Hopefully E. A. Laboratories hired some of Automobile Supply’s old workers. The company now had fifty workers, and needed more room.

They moved to a larger location at 50 Broadway, in the Gretsch Building. Soon that space was too small. In 1919 the Laboratories moved to a new building built near the corner of Spencer Street and Myrtle Avenue. That building had three stories.

Two more were added in 1925, and two years after that, another six story factory building was built next door. The Aufiero family and their car horn company were doing quite well. They were making windshield wipers and signal devices for automobiles, and horns for autos, motorcycles and bicycles.

But while the company continued to grow, genius inventor Emanuel Aufiero was going through a personal hell. The electric automobile horn, that simple idea that had launched his career and made him well-off, had turned out to be the sound that would drive him mad.

The Automobile Supply Company had gone under, in part because of his lawsuit. 500 men lost their livelihoods and Louis Rubes had gone bankrupt and was a sick and broken man. Emanuel Aufiero couldn’t take the guilt or the pressure. He had a breakdown and ended up in a sanitarium.

UPDATE: The grandnephew of Louis Rubes contacted Brownstoner with a letter regarding some of the late automobile company president’s personal history and family fortunes.

Dear Sir/Madam,

I am the grandnephew of Louis Rubes and was born years after his death, but my father, Harry Rubes, was very close to him. There was another horn manufacturer in the 1910s who had an earlier patent. This manufacturer claimed that his patent would apply to the sound made any car horn. He sued Louis and won, but Louis appealed and won the appeal. During World War I, Louis did manufacture munitions for the British army, but this was a financial disaster, and he was forced to sell off his summer estate in New Jersey. My father lived with him in the early 1920s while attending Brooklyn Prep High School. Louis had a chauffeur named Gus who taught my father to drive. After World War I, Louis opened one of the first investment advisory firms on Wall Street. This was very successful, and at his death in 1926, his net worth would have been in the millions in today’s dollars. As a child, I remember visiting his grave in St. John’s Cemetery in Brooklyn and thinking that this was the largest headstone I had ever seen. After the depression hit three years later, the value of the firm plummeted.

Louis went outside the Italian subculture to marry Hilda. After his death, she did become estranged from the Rubes family, possibly because of her objection to the patriarchal family structure. My father continued to run the firm until the start of World War II.

Sincerely,

Richard Rubes

But our story is not over. Emanuel left the sanitarium a cured man, only to find out that his wife had signed away all of his stock in his company. Thanks a lot. Everyone wanted a piece of this poor man. The conclusion of this honking Brooklyn story, next time.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment