Walkabout: 139 Bainbridge Street, a Remarkable House History, Part 2

The house at 139 Bainbridge Street was built in 1903 by developer William Clayton for an upscale buyer. The architect was Axel Hedman. He designed a house with all of the most modern amenities of the day. Please check out Part 1 of our story for the details. The house was purchased by exporter Francis M. Sutton,…

The house at 139 Bainbridge Street was built in 1903 by developer William Clayton for an upscale buyer. The architect was Axel Hedman. He designed a house with all of the most modern amenities of the day. Please check out Part 1 of our story for the details. The house was purchased by exporter Francis M. Sutton, who lived there with his wife Louise and their three children. But this was not a happy home. Next, read Part 3 of this story.

In 1912 Louise Sutton filed for a divorce from her husband of 19 years. The story made the front page of the Brooklyn Eagle on February 20, 1912.

Through her attorney, Louise Sutton told the judge that her husband was having an affair. She said that many of his business trips involved assignations with other women, some of which took place at a resort hotel in White Plains and at a hotel in Manhattan.

She also told the judge that although she and her children lived in a palatial home on Bainbridge Street, she was actually destitute. Her son Sherwood, who was 19, was at Princeton, but the other two children, Doris, 17, and Francis Jr., 14, lived at home.

She said that Francis Sr. was worth over $400,000, and made over $30,000 a year. (In today’s money: almost $10 million, and a salary of about $750,000.) She said she needed at least $575 a month to pay the household bills. That would be about $14K today.

She submitted an itemized list, with groceries, utilities, servants, clothing, entertainment and other monthly expenses. She wanted an alimony that would keep her in the lifestyle she enjoyed.

Photo by Morgan Munsey

Francis Sutton told the court that he had bought her the house. The Eagle article was accompanied by the same photograph used in Walter Clayton’s sales ad, ten years before. Sutton said he still had a mortgage on it, and paid property taxes.

Sutton also told the court that his wife had $8,000 left from $10,000 he had given her the year before, and that she had invested on Wall Street and made a profit. She also got a $250 month allowance from him.

The judge was given a mountain of papers to consider. The newspapers ate this up. They revealed that this divorce was a long time coming, and the couple had been living in separate parts of the large house for years.

Over the years, both husband and wife had locked the other out on occasion, neighbors told the papers. When he got locked out, Francis went to his club, the Crescent Athletic Club, downtown. Louise spent the night at a neighbor’s.

Several days later, the judge ruled in Mr. Sutton’s favor. Until the divorce was finalized, he did not have to pay any support or alimony. Mrs. Sutton, the judge said, was hardly destitute. Her husband’s $250 allowance would continue.

Francis M. Sutton passport photo, 1917, via Ancestry.com

No sooner had the judge issued that ruling than Mrs. Sutton dropped the divorce proceedings and invited Francis home. He moved back in, but things were no better. He claimed he was subject to constant “insult and harsh treatment,” so he left on an extended trip to South Africa.

When he got back months later he moved to the family’s summer home in Allentown, New Jersey, and filed for divorce there.

Husband and wife did not speak directly. All of the correspondence between himself and his wife was carried on through their daughter, Doris, who was now at Vassar.

The case went to court in 1914 in New Jersey, where a judge deemed that Francis had been more insulting and harsh than his wife was, and his suit was tossed out. By this time Louise had once again filed suit for divorce in Brooklyn. The lawyers on both sides were getting rich.

Now neither party was living at 139 Bainbridge. Mrs. Sutton had moved to Flatbush, and Mr. Sutton had the house in New Jersey and an apartment at his club in Brooklyn Heights.

In October of 1914, the divorce case began in a Brooklyn court. All of the embarrassing details were in open court, and therefore in the newspapers.

He accused her of being too friendly with her lawyer. He also testified that he was rich on paper only, and was leveraged up to his eyeballs, and didn’t have the kind of money that she said he had. She once again testified that he was having affairs, and that his “business trips” involved more than legitimate business.

This time the judge ruled for her, and Francis Sutton was ordered to pay her $3,000 a year in alimony. The fate of the house was not mentioned in the papers. He’d always said that he bought her the house, but was it in his name or hers? Perhaps they rented it out while all of this divorcing was going on.

At any rate, although they had moved from Bainbridge Street, the Sutton drama didn’t end. In 1922, Mrs. Sutton was back in court, demanding that her alimony be backed up with a bond of $100,000. She didn’t trust that her alimony would be paid, because Francis had been stepping out with a new floozy – a manicurist named Katherine Vanderpool.

Francis had been so smitten by Miss Vanderpool that he had given her $10K of Sutton company stock and $1,500 in government bonds. He had already written to his youngest son and told him that Miss Vanderpool was “the greatest joy to ever come into my life.”

Mrs. Sutton was afraid that her ex-husband was going to give his new love everything, leaving her with nothing. She said her ex was living a life of debauchery at his mansion in New Jersey, with wild parties, lots of women, and Katherine Vanderpool. She had been living there for months, and he had taken her on his trips abroad.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was Sutton’s annual trip to Australia. Sutton’s company was credited for being the first to export American automobiles to Australia. This time he had taken Francis Jr., now 25, with him to Sydney.

But while there, Sutton had received a telegram from Miss Vanderpool. She had some emergency that caused Francis to rush home, leaving his son to work his way back home on his own. Mrs. Sutton was livid.

The judge took all of this into consideration, and then denied the request. He said that there was no evidence that Mr. Sutton was going to default on his alimony, or any evidence that he was giving all of his money away.

But a year later, it was a different story. Francis Sutton was in court trying to get his alimony reduced. He told the court that his business was failing, and he could no longer afford to pay his ex-wife $3,000 a month. He wanted it cut to $1,300.

He had already sold the New Jersey mansion, and was living at the Crescent Club.

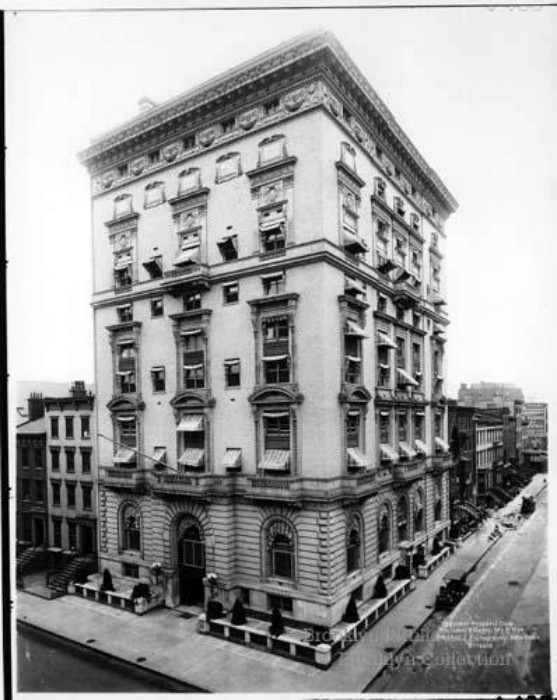

Crescent Athletic Club, Pierrepont Street, now St. Ann’s School. 1910 postcard, via Brooklyn Public Library

It was the end of the high life for Francis Sutton. He died at the age of 69 in May of 1928, in his apartment at the Crescent Athletic Club. The club had been his longest lasting city home since the initial separation in 1912. Miss Vanderpool had long ago vanished in the wind.

Sutton had been a charter member of the Crescent Club, and the members were all at his funeral to see him off. The papers did not mention his family. He is, of course, buried in Green-Wood.

Since Mrs. Sutton had left the house for Flatbush back around 1914, there was no reason to hold on to it. The records don’t show if they rented it out or sold it.

But by 1926, the home was sold to a new owner who would occupy the house for many years. This was not a rich family, but an organization offering aid to women who found themselves alone and friendless in a merciless city. This organization was called the Welcome Home for Girls, and their story continues next time.

Photo by Morgan Munsey

Top image from Brooklyn Eagle, 1903

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment