Black Pride, Kung Fu and Social Justice: The Life and Times of Bed Stuy’s Slave Theater

For many people in Bedford Stuyvesant, home to Brooklyn’s largest African American community, Fulton Street’s Slave Theater is not just a building — it’s a metaphor. The name has always been uncomfortable. Who wants to be reminded of slavery? Who wants to be reminded of slavery when going to the movies, of all times? That’s…

For many people in Bedford Stuyvesant, home to Brooklyn’s largest African American community, Fulton Street’s Slave Theater is not just a building — it’s a metaphor.

The name has always been uncomfortable. Who wants to be reminded of slavery? Who wants to be reminded of slavery when going to the movies, of all times?

That’s just why Judge John L. Phillips chose the name.

A Short History

The theater at 1215 Fulton Street, originally named the Regent, has been around since 1914. At that time, central Brooklyn had a multitude of theaters, assembly halls and entertainment spaces, many along Fulton. When this one was built, the much larger Fulton Theater was only a few doors down, on the site of the bank building that’s now a Walgreens.

The Regent was always a smaller, secondary theater. Its unknown architect designed a classic theater space with a raked seating area pitched toward the orchestra pit, behind which was a classic proscenium stage. The theater was set up for vaudeville, theater and cinema.

The house only held 534 seats, and the building’s second floor, which had a separate entrance, was rented out as offices. The theater’s décor was no fantasy pleasure palace, but more of an intimate concert hall with late-18th-century-style elegance. It featured coffered ceilings, elegant chandeliers and sconces, and simple molding-framed walls.

The “Kung Fu Judge”

Judge John L. Phillips bought the theater in 1984, one of two theater spaces he purchased. The other was the Black Lady Theater, at 750 Nostrand Avenue. He also invested in about 10 pieces of residential real estate, some near his own home on nearby Herkimer Street.

The judge was known in the Bed Stuy community as the “Kung Fu Judge.” He was a larger-than-life figure, a black judge on the Civil Court bench in Brooklyn at a time when there weren’t too many of them around.

Judge Phillips had a 10th-degree black belt in martial arts, and in his spare time opened a dojo in the community, where he taught his own fighting style called the “Gorilla-Gnat System of Scientific Movements and Defensive Fighting.”

He also fought with Brooklyn’s political establishment, both black and white, and was no friend of either Brooklyn Democratic boss Meade Esposito or District Attorney Charles “Joe” Hynes.

In the early ’80s, the judge made a movie about an interracial love story, which he financed himself. When he couldn’t get anyone to show it, he bought the old Regent Theater and showed it there.

He changed the name to the Slave Theater, he said, to remind everyone in the community, including himself, where they came from. He didn’t particularly care that many in that community were offended by the name, either. He transformed the marquee, then set about transforming the inside of the theater.

He had artists paint murals on all of the walls, mostly depicting black heroes throughout history, from many countries. Dr. King, Marcus Garvey, Toussaint L’ouverture and many others graced the walls, as did Kung fu master Bruce Lee. The artists also painted anthems and quotes, all highlighting black history and positive affirmations of unity and culture.

Although the Bed Stuy community had mixed feelings about the name, there was a general consensus that having the Slave Theater there was a great thing. It was the only remaining movie theater in Bed Stuy, and it was owned by an African American, perhaps the only major commercial building on that entire strip to have a black owner.

Bed Stuy in the 1980s

Bedford Stuyvesant was in the middle of hard times. Many of Bedford’s residential streets remained the working blue- and white-collar enclaves they always were, but the commercial core was declining.

Almost all of the neighborhood’s manufacturing jobs had moved out in the 1960s. Bed Stuy had a thriving commercial core centered on Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue throughout most of the century, but by the 1980s most of the old stores were leaving or gone, leaving empty storefronts and new stores selling only the cheapest of merchandise. Even Woolworth’s left.

Unemployment, poverty and a new drug called crack were not helping Bed Stuy shed its reputation as the “worst ghetto in America.” But that didn’t mean people were not trying to effect positive change.

The Slave Theater’s Glory Years

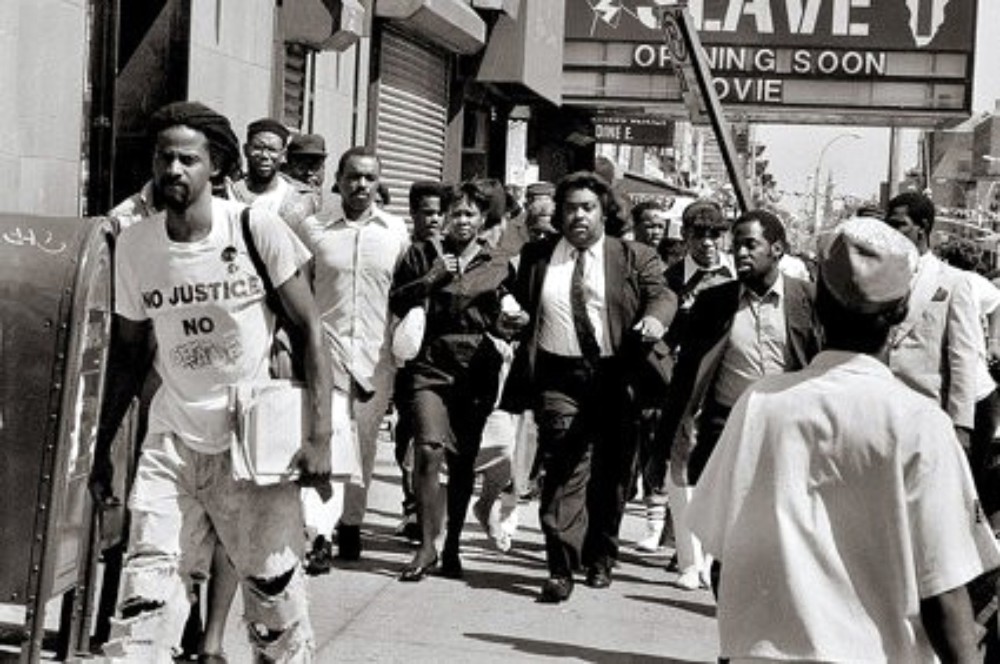

Judge Phillips’ theater became a nexus for community activism. In 1986, after Michael Griffith was chased to his death by a mob in Howard Beach, Phillips allowed the Slave Theater to be the meeting space for the Rev. Al Sharpton and other community activists.

Sharpton, attorney Alton Maddox and other organizers held Wednesday-night rallies at the theater, and coordinated marches and other protests here. The theater became a nexus for a new social justice movement.

New York’s black community had always rallied in Harlem, because that’s where the movers and shakers of the community lived. Sharpton et al had galvanized the movement, snatched the attention away from Harlem, and brought it to Bed Stuy, Brooklyn.

For several years afterward, the Slave was a busy place, and not because of the Kung fu double features. Other speakers began using the space, and a church rented the offices upstairs for its worship services. Judge Phillips, who had a dream of a place where black pride could shine and be appreciated, had seen that dream come true in many ways.

Unfortunately, the dream ended when the judge lost everything, including his mind. That was followed by one of the most blatant and egregious cases of fraud, misconduct and misappropriation Brooklyn has ever seen.

Decline of the Kung Fu Judge and the Slave Theater

In 2001, two doctors testified to early signs of dementia in Judge Phillips, and the court appointed a guardian over his estate. That guardian then proceeded to rack up close to $2 million in tax debts to the U.S. government and helped herself to more than $400,000 of Judge Phillips’ money — which she was eventually ordered by a court to repay, according to the New York Times.

Phillips died in 2008 of neglect, freezing to death in his nursing home. But that’s a story in itself.

His buildings and debt passed to his nephew in Ohio, the Rev. Samuel Boykin. The nephew put the theater on the market in 2009, but it didn’t sell. In 2012, the property went into foreclosure and only narrowly missed being auctioned off.

Two of the judge’s former associates, Clarence Hardy, the former caretaker, and the Rev. Paul Lewis, who rented upstairs, contested Boykin’s ownership of the theater. But the courts upheld Boykin’s ownership and he sold the Slave Theater and two adjacent sites to real estate developer Yosef Ariel in 2013 and 2014. Just last month, Ariel sold the three properties to Eli Hemway for $18,500,000. On Wednesday, a construction contractor filed permits to demolish the two-story structure.

Today, Phillips’ empire is gone, and the last parcel — his Slave Theater — is about to be torn down. Thank goodness he didn’t live to see it take place.

Related Stories

Man Protests Slave Theater Demo by Threatening to Jump From Top of Marquee

Bed Stuy’s Iconic Slave Theater Sells to Developer, Already Hit With DOB Complaints

Suzanne Spellen, aka Montrose Morris, Is Writing Brownstoner’s First Book

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

[sc:mailchimp-books ]

Thank you so much for doing this story. Very sad. I never knew about the name change.

Really interesting piece – especially considering Eli Hemway (Hamway? I’ve seen it spelled both ways) is also the landlord of that huge commercial property in Gowanus that just kicked out dozens of artists – he seems to either have a penchant for swooping into a neighborhood and pissing everybody off or he’s just in the wrong place at the right time.

Thanks Suzanne. Such a tragic bizarre story. It’s a big loss for Central Brooklyn that this theater will not be brought back to life.

Really interesting post. Thanks MM.