From Redlining to Predatory Lending: A Secret Economic History of Brooklyn

Throughout much of the 20th century, half of Brooklyn was considered undesirable and too risky for loans and investment.

Photos of Brooklyn by Dinanda Nooney and P.L. Spurr via NYPL. 1938 Brooklyn Community Zoning Map via National Archive

You may have heard the term “redlining” in discussions of neighborhoods like Bed Stuy or East New York. But do you really know what it means? And how the effects of discriminatory lending practices are still felt in Brooklyn today?

A quick definition

Redlining was the practice of refusing institutional financial support — like a mortgage or insurance policy — to someone because their neighborhood was thought to be financially risky. Back in the 1930s, a number of factors were used to determine the area’s risk.

Like the presence of “a single foreigner or Negro,” as one neighborhood appraiser is quoted as saying in Beryl Satter’s book Family Properties. If your neighborhood had black people, immigrants, old houses, or schools with a population of “inharmonious racial groups” it was officially deemed a financial risk.

As you can imagine, the racist denial of financial services and infrastructural improvements to entire neighborhoods had a profound impact on Brooklyn and its diverse communities. The effects of redlining are still felt today on our city’s streets. Here is that story.

How redlining came to be

The nation was in the grip of the Great Depression when the Federal Housing Administration was established in 1934. Its job was to jumpstart the housing industry by making federally insured, longterm, low-interest loans available to potential homebuyers.

The FHA worked with the insurance and banking industries to come up with guidelines to ensure their investment would not go to waste. It created a new government agency: the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC).

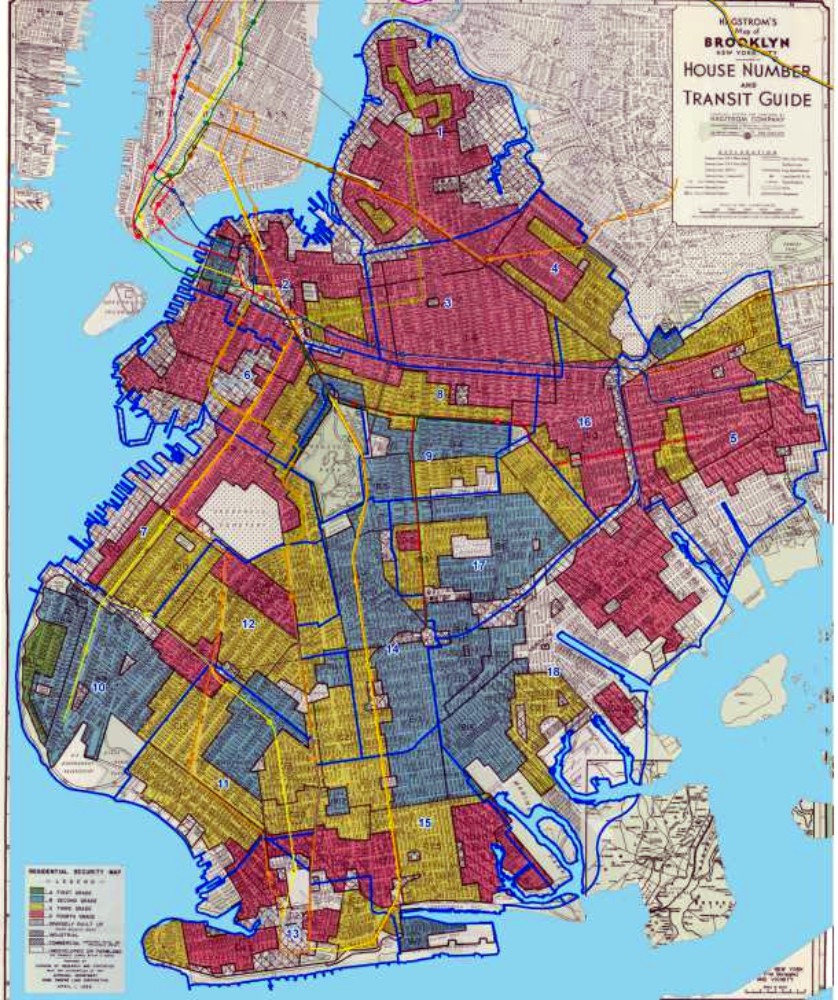

In 1935, the HOLC was asked to prepare “residential security maps” for 239 American cities. The maps would show which neighborhoods were deemed to be the most desirable for investment, and would give lenders their best return. The neighborhoods were ranked by the color of their respective zones.

The four zones: green, blue, yellow and red

Neighborhoods lined in green were the best. In many cities, these zone “A” areas were new neighborhoods with new construction, usually suburban. If more urban, they were the affluent areas where a bank’s money was guaranteed.

Blue zones, the “B” areas, were good too, but not the best. They were listed as “still desirable.”

Yellow, or “C” zones were in transition. They were usually the older parts of cities that were headed downhill. Incomes were falling, the housing stock was no longer fashionable and further decline was in the air. These neighborhoods were always adjacent to the worst designation — the “D” zones.

These neighborhoods were the least desirable. They were usually in the city center, were older districts, and were minority and immigrant neighborhoods. These neighborhoods had a big red line drawn around them — or, as in the case of our 1938 map, red-filled areas.

Banks lent to the top two tiers, offering lower rates and more funds. They made no loans to anyone seeking a mortgage within the red borders, no matter how qualified the borrower happened to be. Redlining was born.

By 1938, half of Brooklyn was redlined

We can see how the zones shake out in the fascinating 1938 map of Brooklyn prepared for the HOLC. Only two neighborhoods make the “A” listing — parts of Brooklyn Heights and the Shore Road area of Bay Ridge.

Many more make the secondary blue zones, including most of Victorian Flatbush and Midwood, Flatlands, Park Slope’s Gold Coast, and prime blocks above 7th Avenue. Also included are Bay Ridge and Dyker Heights, and the Prospect Lefferts Gardens area, up around the mansions of President Street and Eastern Parkway.

But more than half of the rest of Brooklyn was deemed declining or totally unacceptable. Yellow-zone neighborhoods included the rest of Park Slope and Prospect Heights, parts of Clinton Hill, most of Bensonhurst, Borough Park, Cypress Hills, Sea Gate, Marine Park and more.

Red zones were widespread and included the neighborhoods of Bedford Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, Ocean Hill, Brownsville, Bushwick, Williamsburg, Greenpoint, East New York, Canarsie, Sunset Park, Gowanus, Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens, Fort Greene, Red Hook, Coney Island and the Sheepshead Bay/Gerritsen Beach area.

Yes, according to the real estate and banking boards that determined where the FHA money went, half of Brooklyn was totally unacceptable or on its way there, including almost all of Brownstone Brooklyn.

What did this really mean?

The HOLC model was based on a lifecycle assessment of neighborhood change. The theory was that neighborhoods inexorably declined as housing stock decayed and architectural styles changed. This lowered values to the point that a “lower-grade population” began to “infiltrate” the neighborhood.

Working-class or foreign-born whites compromised a neighborhood’s integrity and accelerated the decline of housing values and neighborhood desirability, according to the HOLC model, making for a “C” listing, but far worse was the presence of black people, which precipitated the final demise of the neighborhood.

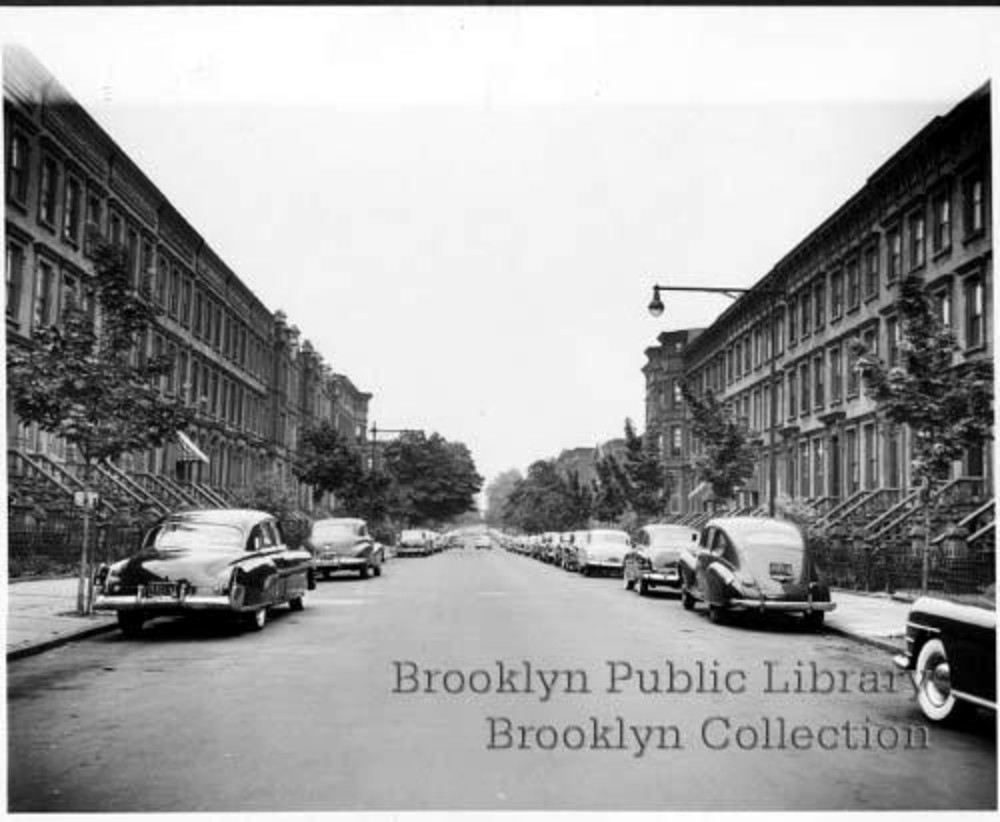

Virtually all of Brooklyn’s redlined neighborhoods had black populations. Many also had large immigrant and working-class populations. They also contained much of the city’s oldest housing stock.

The threat of the “contagion” of black people was so omnipresent in the criteria that many neighborhoods — like Williamsburg — may not have had large black populations themselves, but were marked risky for being next to black neighborhoods. The HOLC guidelines warned of black people passing through these neighborhoods, and eventually moving in.

Armed with the redlined maps, the city’s banks, mortgage and insurance companies could now justify unfair lending and policy practices. They closed their doors to redlined neighborhoods, and lent very sparingly to those in the yellow lined areas.

A number of municipalities and businesses pulled their resources and investment out of redlined neighborhoods too, allowing infrastructure and services to fall apart.

In Brooklyn, it created 20th-century Bedford Stuyvesant — at the time considered one of the largest ghettos in America — which stretched from Williamsburg to Flatbush, Downtown to Bushwick.

Those in redlined neighborhoods survive

For the people who lived in Bed Stuy and other redlined neighborhoods, the sale of real estate went on. If large real estate firms and banks didn’t want to deal with the neighborhood, then a separate system of brokers, financial institutions and lenders would carve out their own niches.

African-American real estate firms were established and sold only within the community. They advertised in the neighborhoods through word of mouth and in black newspapers like the Amsterdam News.

Local black churches such as Concord Baptist Church and others began home-buying clubs, allowing members to pool money to make down payments. The few black banks, savings and loan associations and credit unions offered mortgages and savings clubs as well.

Private lenders advertised in the communities, offering mortgages, but with huge interest rates and penalties. They were the communities’ first predatory lenders.

In spite of the exorbitant interest rates, they were often the only game in town. Black homebuyers worked two and three jobs to make the payments. They subdivided the row houses into apartments and rooming houses, families often taking up very little personal space to get higher monthly income coming in.

While many parts of the huge Bed Stuy “ghetto” did suffer, thousands of determined homeowners maintained pristine and safe blocks, both then and now.

The end of redlining and rise of predatory lending

Redlining continued through the 1960s and ’70s. Even the new homeowners in Park Slope during the great brownstone revival found many areas still considered off-limits by banks. But as more people began moving back into the urban core, banks realized that this was a fresh new market — these were upscale people with money.

Redlining didn’t go out with a bang, but with the soft swoop of a bank card in a terminal. All of a sudden, all of the city’s major banks wanted to open neighborhood branches and lend to the community. They began sponsoring rehab programs in conjunction with the utility companies.

And in formerly redlined areas that did not become white and wealthy in the 20th century, new types of discriminatory lending practices arose to take redlining’s place.

As property values increased, the predatory lenders came out in full force. Homeowners in previously redlined minority areas were targeted for subprime loans. The predatory lending in the areas — sometimes called “reverse redlining” — had little to do with an individual’s credit score and everything to do with their location.

In addition, investors began going door to door within formerly redlined neighborhoods, offering cash buyouts and loans to repair aging properties. Some were unscrupulous, offering less than the market value of a property or poor loan terms.

Elderly homeowners were especially vulnerable, not always aware of the market value of their homes or the conditions of their loans. Some investors went beyond poor terms and into out and out fraud, taking ownership under the guise of a loan, not paying the full amount promised, or even forging signatures.

As the economy faltered in 2008 and afterward, foreclosure and predatory lender maps began to look like the old HOLC maps. The minority-heavy neighborhoods of Bed Stuy, Bushwick, East New York and Ocean Hill showed the greatest number of foreclosures. Homeownership, so hard won in spite of discrimination, was once again slipping from the grasp of many minority homeowners.

Today, neighborhood groups and Brooklyn officials are working to educate residents about mortgage scams prevalent in these areas — taking small, necessary steps on the long road to righting the wrongs of discrimination.

Related Stories

Suzanne Spellen, aka Montrose Morris, Is Writing Brownstoner’s First Book

Walkabout: Saving Bedford Stuyvesant, Part 1

What Is Gentrification, Anyway?

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment