Past and Present: The Max Huncke Chemical Company

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. A look through the Brooklyn Public Library’s Brooklyn Collection revealed this picture of an attractive factory building on the Gowanus/Park Slope border. Today it’s the site of one of 4th Avenue’s many automobile service stations. Tomorrow it will probably be a condo tower, but 85 years ago, this…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

A look through the Brooklyn Public Library’s Brooklyn Collection revealed this picture of an attractive factory building on the Gowanus/Park Slope border. Today it’s the site of one of 4th Avenue’s many automobile service stations. Tomorrow it will probably be a condo tower, but 85 years ago, this was the home of the Max Huncke Chemical Company. There are chemical companies and there are chemical companies. This one specialized in chemicals for embalming. It turns out that chemist Max Huncke was the grandfather of the modern embalming process.

Death practices in the United States have changed a lot in the last century and a half. Before the Civil War, there was no standard embalming as we know it now. When someone died, the body was cleaned up, dressed, laid out at one’s home for a funeral service, and buried as soon as possible. The Civil War introduced dying far away from home to a great many families. Techniques were invented to keep a body from decomposing too fast, so that it could be shipped back home for the funeral. Various chemicals were experimented with, but ice remained the best and easiest method.

Even well into the 1880s, being “on ice” was the general method of preservation, but as can be imagined, there were limitations to that. The Victorians had turned death and funerals into the grand send-off that we know now, just taken to extremes we find bizarre and morbid today. Jewelry and artwork made from the deceased person’s hair will never be popular again, thank goodness. All of these extended death ceremonies made the idea of embalming attractive. Chemists were hard at work trying to find a combination of chemicals and procedures that would keep a body from actively decaying too fast, allowing the loved one to have an open casket funeral.

In 1867, a German chemist named August Wilhelm Von Hoffmann invented formaldehyde, the basis of modern embalming fluids. Later chemists also used an arsenic solution to retard putrification. Here in America, formaldehyde, arsenic and other chemicals were taken up by an immigrant German pharmacist and chemist named Max Huncke. In 1886, he and C.B. Dolge, another German immigrant, who had business experience as an inventor, artist and entrepreneur, established a company specializing in embalming solutions and supplies.

The company went by several names over the next few years, being known as the Brooklyn Fluid Works, Embalmers Supply Company, the Brooklyn Embalming Fluid Company, and the Dodge & Huncke Company of Brooklyn. Dodge was the Americanization of Dolge. In 1890, the company moved their headquarters to Westport, Connecticut, and three years later, Dolge bought Huncke out. The Embalmers Supply Company became ESCO, and they are still in business, the largest American supplier of embalming chemicals, supplies, and mortician’s equipment.

Dolge & Huncke’s company was the first to introduce formaldehyde to American morticians. They were also the first to manufacture it. Previously, all of the chemicals and tools were imported from Germany. They invented and manufactured the first embalming tools made in the United States, the first morgue table, the first vascular embalming process, the first company to introduce a tissue filler, and many more firsts that would only be familiar to morticians and embalmers.It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that the two men knew more about embalming than anyone else in the country.

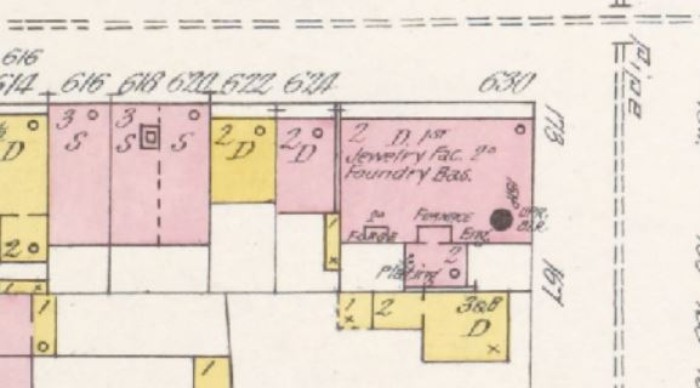

After the buy-out, Max Huncke opened his own chemical works called the Max Huncke Chemical Company. The building in the photograph started out as a jewelry factory, built sometime between 1880 and 1888. Max Huncke took over the building sometime around the turn of the 20th century. There isn’t a lot of documentation here. His company had several patents, and was quite successful, at least up until his death. They were very involved in citizen’s committees during World War I, and management in the company made the news for a variety of social events.

Max spent most of the rest of his life on the embalmer’s lecture circuit. The funeral business really took off in the 20th century. As modern life was changing, so was modern death. Whereas everyone, rich or poor, once had their funerals in their home, life in the 20th century was making that more and more difficult. Apartment life, among other things, killed off the home funeral. Funeral parlors and houses of worship were the place to have a funeral now, not the home.

Funeral directors now had larger jobs, and were offering more to their clients, who now expected more. Schools of mortuary science were established, and morticians began having conferences and trade shows. A mortician was now a specialized professional. Max Huncke, as a pioneer, was a popular keynote speaker. I found references to him speaking at funeral industry conventions up until his own death in 1929. His talks had titles such as “The Embalming Question.”

He was 81 years old, and he died peacefully at home. No doubt, he was embalmed. He lived in Bay Ridge on Ridge Boulevard, and was survived by his widow. I was not able to find out what happened to his company. The photograph is dated 1933, after his death. It looks closed, but it’s hard to tell. I was not able to find any records of the company after that, so I don’t know what happened to it. I do not know when the building was torn down. Today, a non-descript garage building stands in its place.

Interestingly enough in a neighborhood that has seen great change, many of the surrounding buildings are the same in both photographs. The house next door is still standing, albeit greatly altered. On the corner, on 18th street going towards Third Avenue, the same tenement buildings are still there. Who knows how long this will be the scene on this corner. I suspect not long. Max Huncke’s name pops up because of thick empty glass bottles sold on Ebay and other sites. They once held embalming fluid, and have his company name embossed in the glass. As long as there are collectors, Max Huncke lives on.

GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment