Past and Present: The Haxtun Cottage of the Children’s Aid Society

A Look at Brooklyn, then and now. Someone wise once said that you can judge a society by how they care for their children. One might also add to that statement by adding how a society cares for the crippled and disabled children and adults, as well. Long before there were government agencies, legal protection…

A Look at Brooklyn, then and now.

Someone wise once said that you can judge a society by how they care for their children. One might also add to that statement by adding how a society cares for the crippled and disabled children and adults, as well. Long before there were government agencies, legal protection or safety nets for the most powerless people in our society, there were still those whose hearts and hands were opened to help. Late 19th century Brooklyn was much like today, with a great many upwardly mobile and wealthy people spread across most of the city. There was a respectable middle class, the working poor, and a large population of destitute and desperate people.

Among the wealthier sets, charity was tied up with faith and community. There were those who gave because they wanted to impress their peers and the rest of the world, and those who gave because it was an expected duty. And then there were those who truly believed that their wealth, position, and often their faith, mandated that they not only give generously, but be active as well, taking the time to be on committees, fund raise, visit the poor, and give magnanimously of their time and money. The Victorians set up a number of important charities during this period, and many of them are still with us today. One of these was the Children’s Aid Society.

The Children’s Aid Society was founded in New York by Charles Loring Brace and other social reformers, in 1853. They believed that there should be an alternative for poor and orphan children besides the almshouses, orphan asylums or the streets. The Society believed that the answers to transforming New York’s orphans and street children into self-reliant members of society were gainful work, education, and a wholesome family atmosphere. They were the first to offer school lunches for hungry kids, and establish summer camps out of the urban environment where city kids could run and play and get out of the city, for some, the only time in their lives. They also established the Orphan Trains, but that’s a story for another time.

It’s hard to imagine how awful the slums of late 19th century and early 20th century New York really were. Urban poverty today, which is certainly no picnic, was nothing like poverty then. The slums were worse, the overcrowding more severe, and there were no amenities like toilets, baths or showers. People crowded into hot, dark and airless tenements where it was impossible to have privacy, and it was impossible to keep clean. There was very little nature around to relieve the experience of the dirty, noisy and overcrowded streets. Summers were especially hellish.

Social safety nets like welfare, food stamps and subsidized housing were decades away. The orphanages and almshouses were full, and many children were sent to work by the time they were ten, or even earlier. The streets were full of homeless children, or kids working as newsboys, messengers, match girls, factory workers, or worse. The Children’s Aid Society established the Newsboy’s Home in Brooklyn Heights to provide food, education and shelter for many of these boys, and there were homes and programs for girls, as well. All of the programs included education, teaching basic education and skills to a population that often was not enrolled in any school. Many of the newsboys could not read the papers they sold.

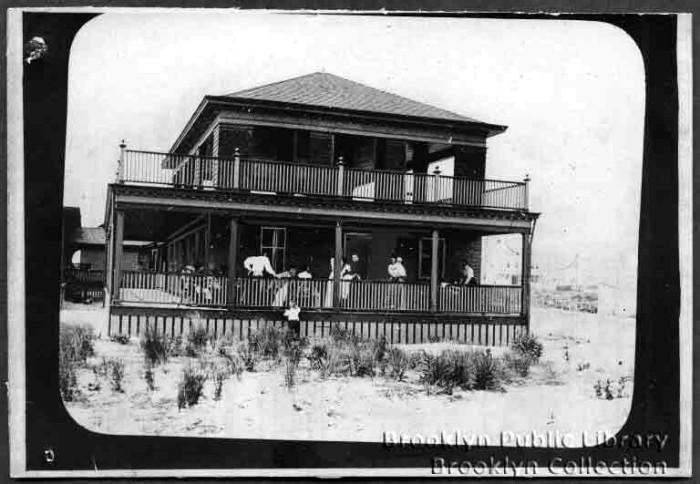

By the late 1890s, the Children’s Aid Society of Brooklyn had established a summer camp in southern Brooklyn. Through the generosity of wealthy patrons, including the powerful ladies of the Astor, Vanderbilt, Phelps and Roosevelt families, and with the backing of many of Brooklyn’s churches, a camp was established in Bath Beach where groups of children could spend one week out of the city. There, they enjoyed the beach, the open air, learned about nature, and were able to go on picnics, and just be children. One of the Society’s wealthy patrons, Mrs. Benjamin Haxtun, paid for the building of a large cottage set aside especially for crippled children. It was called Haxtun Cottage, and is the building in the historic photograph on the left.

Haxtun Cottage was part of the Society’s larger compound at Bath Beach. There they had a large Victorian “cottage” for the sick, which was a children’s hospice near the beach. They also had the Haxtun Cottage, as well as another cottage for day camp children near the beach. A child attending the overnight program stayed for a week. They took turns alternating weeks between boys and girls. The day children numbered in the thousands each week. The children who attended ranged in age from 6 to 13. The Society did not discriminate between Christian and Jew, and had children of every race attending, according to newspaper accounts.

The children at Haxtun Cottage were attended by nursing staff, and seemed to be cared for even more tenderly, as most were not able to run and play with the other children. The cottage was furnished with books and toys, and the children were taken outside as often as possible. They came from hospitals and homes from across the entire city. Even after Mrs. Haxtun’s death in 1898, the cottage remained a special part of the Society’s mission, and remained funded, even as their general summer programs expanded and changed with the times.

By 1907, the Society had grown the Bath Beach facility to include a boy’s camp, and another facility where mothers could come with their children. There was also a special program for mothers with sick babies and children. Many of these little ones suffered from the diseases of poverty and overcrowding; cholera, chronic diarrhea, and asthma. The staff that ran the programs were always amazed at how quickly the children and the mothers responded to the clean, fresh air, and a clean environment. It was too bad those trips were only a week long, and they had to go back to the city.

Fund raising for the summer camps, as well as the Society’s many other programs was a full time job. Individuals, churches and other organizations were urged to donate towards a specific object or program, giving the donor the opportunity to know where their money was going. Someone could donate a cot, a wagon, or wheelchairs. You could buy chairs for the dining room, or bedding and mattresses. You could also fund a class to teach girls how to sew, or boys, carpentry. Fund raising fairs and pledge activities took place all year, but in the summer, patron could go out to Bath Beach and see the joy in the playing children.

In 1923, the Society celebrated the 50th anniversary of the summer camps at Bath Beach. They now had a larger program in place on Staten Island, which could handle many more children. It would be the last anniversary in Brooklyn. Bath Beach was changing, as development for an expanding population was turning all of Brooklyn into city blocks filled with homes and businesses. The cottages were now at 1750 Cropsey Avenue. One by one, the day camps, the children’s hospice, and the sleep away camps closed, and were moved elsewhere. The Haxtun Cottage was the last facility to leave Bath Beach. When the famous New York photographer Berenice Abbott took this photograph of the recently abandoned Haxtun Cottage, the year was 1936.

The cottage was only a block away from the ocean in what is now considered Bensonhurst. That year, Ms Abbott took several photographs of restaurants and hotels in that area, all abandoned and closed up. They would all be torn down for development. Today, the site of the cottage is covered by rows of garages or storage units, the site advertised as a perfect site for further development. At the rate real estate is growing, it won’t be long. Meanwhile, the Children’s Aid Society is still going strong, still sponsoring its Fresh Air Programs, and still helping the most vulnerable in our expanding society.GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment