Past and Present: The Evolution of 265 Livingston Street in Downtown Brooklyn

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. Before Downtown Brooklyn was the shopping mecca of Brooklyn, it was a residential neighborhood. In the 1860s and ‘70s, many of the most commercially developed thoroughfares, like Fulton, Schermerhorn, Livingston and Willoughby were residential. In the mid-19th century, all of these streets were lined with wood framed, and…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

Before Downtown Brooklyn was the shopping mecca of Brooklyn, it was a residential neighborhood. In the 1860s and ‘70s, many of the most commercially developed thoroughfares, like Fulton, Schermerhorn, Livingston and Willoughby were residential. In the mid-19th century, all of these streets were lined with wood framed, and later, masonry row houses. There were even a few free standing homes as well. But as Brooklyn’s commercial core spread out from what is now Dumbo, the homes began to disappear or were renovated to include store fronts. Gage and Tollner, one of Downtown’s most famous restaurants, was once a home.

A look at old newspapers and maps show several houses where this building now stands. These were not tenements, but the homes of well-to-do people; merchants, lawyers, doctors and other professionals. By the 1880s, the homes were almost gone. Large dry goods stores, theaters and restaurants were rising all along Fulton Street, and Livingston was becoming a secondary street for shops and theaters. Seven wood framed houses sat on this site, which were razed for the New Montauk Theater, which was built here in 1895.

It was lauded as one of the great theaters of its day, and was designed by John McElfatrick, and paid for by Senator William H. Reynolds, one of Brooklyn’s most prolific developers, and soon to be owner of the Dreamland Amusement Park on Coney Island. Always a man of great theatricality, Reynolds got a theater that dripped with marble, was swagged with hundreds of yards of draperies, and painted and gilded on every surface. They also put on plays.

But it didn’t last. The curtain closed for the last time on May 28, 1925. The New York Times noted that the theater had only been built thirty years before, and had hosted all of the leading stars of the past three decades. But it had been purchased by Louis Gold & Co, a developer. He intended to tear it down and replace it with a loft building taxpayer with stores on the ground floor. A taxpayer is a building of no particular style or quality that just sits there and pulls in rent and taxes. Goodness knows there are enough of those around.

So the New Montauk Theater, with all of its splendid décor was torn down and carted away. Fortunately, Louis Gold was having financial problems and the site was sold at auction. The buyer was J. M. Kalt. He paid $720,000 for the large site, and planned to spend another $100,000 on the building. He planned a large three story store and showroom building, built with “modern construction.” The building would have five store fronts on Livingston and two more on Hanover Place. The upstairs floors would be showroom and warehouse space.

Kalt was excited about his purchase. He and other downtown landlords realized that Livingston Street was about to blow up, as the stores on Fulton were expanding, more retail space was desired, and the new subway lines underground were being built as they spoke. They would bring more people than ever into Downtown Brooklyn, and onto Livingston Street. This prime retail site needed something better than a taxpayer. He hired the firm of Selig & Finkelstein to design his new store building.

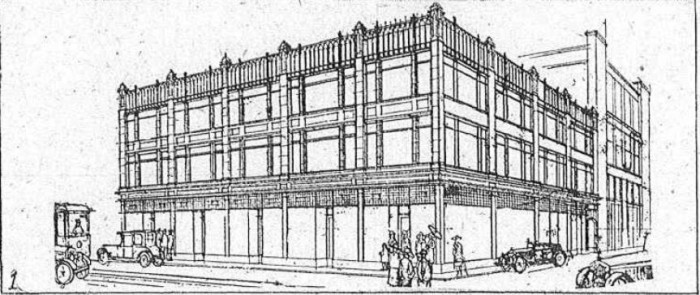

Selig & Finkelstein were well known architects during the early to mid-20th century, here in New York City. They built apartment buildings, stores and suburban homes throughout Brooklyn and Queens. They designed a beautiful store building for their client. The sketch of the building was printed in the Brooklyn Eagle on July 4, 1926. In November of 1927, the papers announced that the entire building was going to be leased by Spear & Company Furniture. They signed a lease for 21 years, and were planning extensive alterations to suit their needs.

Spear & Co. Furniture, known everywhere as just Spear’s, had been founded in 1893 in Pittsburgh, by three brothers; Nathaniel, Alexander and Maurice Spears. They had built up a successful company by knocking off popular high-end designs of the day and mass producing them with cheaper materials and finishes. Their middle class customers loved it, and by 1903, the company had expanded into many major cities, including Manhattan.

By the late 1920s they had a large warehouse on W. 23rd Street in Manhattan, as well as a store on 34th, next to the Empire State Building and in a few years would open a large store in Jamaica, Queens. This new Livingston Street store was another jewel in their New York crown.

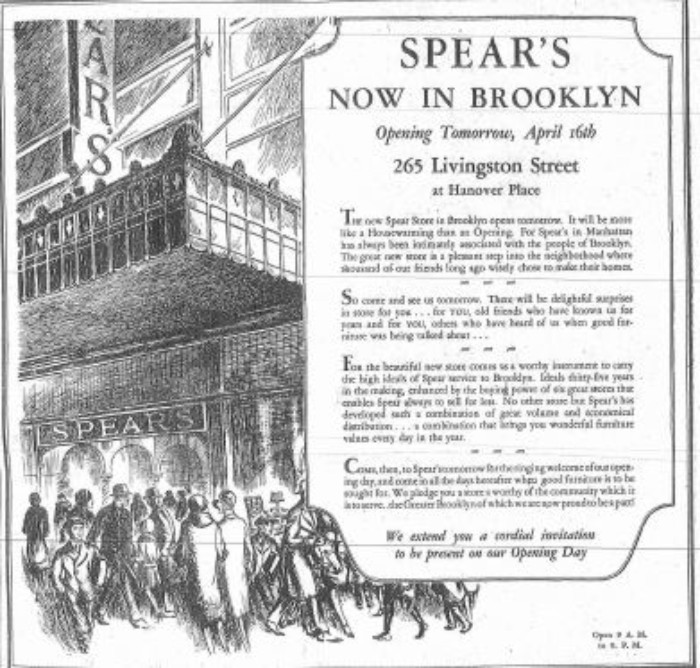

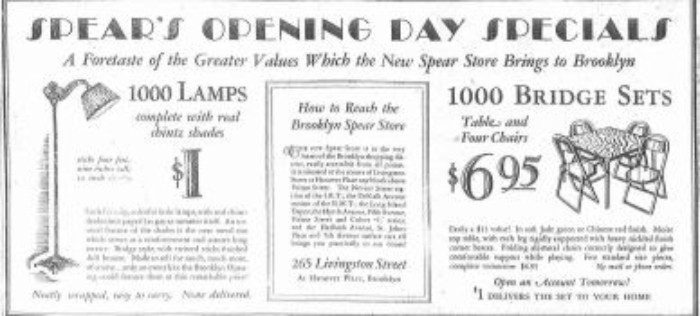

The grand opening was announced by a large three-quarter page ad in the Brooklyn Eagle. The doors to the new Spear’s would open on April 16, 1928. As an enticement to come on by, they were selling 1000 pot metal floor lamps with shades for $1.00, and 1,000 folding card table and chairs set for $6.95.

As America slid into the Great Depression, Spear’s survived by instituting a policy that became their motto – “We give you time.” They offered no money down, paid off over time, with interest, for purchases. Many people did not have the money to buy large, expensive items like furniture outright, and this method was a perfect way for newlyweds to buy furniture, or for someone to replace that broken couch, or just redecorate. Spear’s made much more money charging interest than they would have made for just selling goods, a formula that kept many a store going through the Depression, and on to today.

But the ride always has to come to an end. By the 1950s, only Nathaniel Spears was still alive. His brothers’ heirs were not all that interested in the business, and began to divest themselves, closing stores and selling off assets. They closed the New York stores in the mid-1950s. Nathaniel died much later, in 1968. He must have been heartbroken.

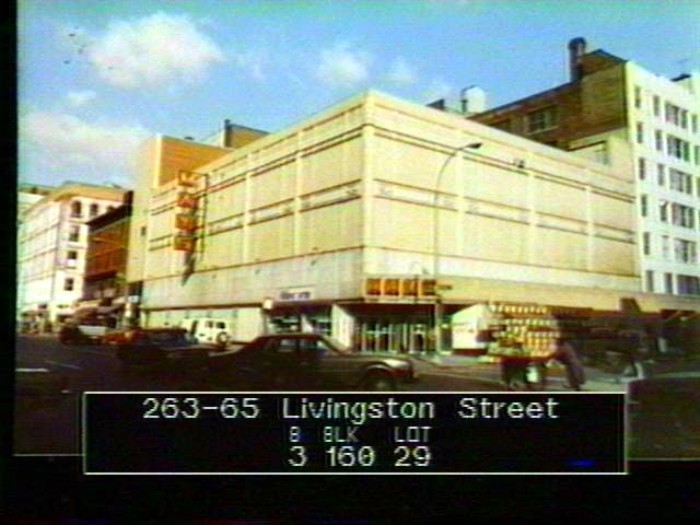

The grand Spear’s store became part of May’s Department Store, which had its main entrance on Fulton Street and a back entrance here. By the 1980s, May’s was gone too, and their space was subdivided into smaller stores. The Livingston store has been home to Cookies Department Store for many years. They are Downtown Brooklyn’s largest children’s clothing store, and do a brisk business selling school uniforms.

They’ve covered up much of the building’s best features, painted over the windows, and put up some very large signage. But the building is still under there, and looks pretty much intact. It wouldn’t take much to bring it back, if that ever happens. Interestingly, the J.W. Mays Corporation still owns the building.GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment