Past and Present: The Brighton Beach Hotel

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. Even though winter has not even officially begun, already we are getting nostalgic over the thought of summer. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a luxurious summer resort by the sea, where you could have accommodations worthy of your pocketbook and status? There you could be waited on…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

Even though winter has not even officially begun, already we are getting nostalgic over the thought of summer. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a luxurious summer resort by the sea, where you could have accommodations worthy of your pocketbook and status? There you could be waited on hand and foot, enjoy fine dining, be entertained by the biggest stars of the day, and best of all, enjoy the cool, salty breezes and one of the finest beaches on the Atlantic Ocean. Would you have journey to Palm Beach or some Caribbean Island? Nope, you could take the subway. Because the beach resorts of Gravesend, Brooklyn were the place to be back in the latter quarter of the 19th century.

It all started with a man named William A. Engelman, who had made a fortune during the Civil War selling horses to the Union Army. He took some of that money and bought several hundred acres of beachfront property in Gravesend for the princely sum of $20,000. This was in 1869. He had big dreams, and he named his beachfront property Brighton Beach, after the famous resort town in England, a popular summer destination for British royalty and the aristocracy.

By the end of the 1860s, the first train line had been established to bring day trippers to the beach. There would be two more train lines by 1887, all originating somewhere in downtown Brooklyn. Tourists were also coming by sea, taking steam boats from Manhattan. Engelman built a pier to accommodate the boats, and then built the Ocean Hotel for his guests in 1871. By the middle of the decade, Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted had finished Ocean Parkway, which stretched from Prospect Park down to the sea. It was soon crowded with carriages and riders eager to get out of the city, and take the scenic route to the shore. The parkway let them out almost at his hotel’s front door.

In 1878, Engelman completed his grand Brighton Beach Bathing Pavilion and Ocean Pier, which could accommodate 1,200 bathers. There was no such thing as lying out on the beach with a towel and your skimpy bathing suit in those days, the name “bathing suit” says it all; people put on special clothing and walked out into the shallows and splashed water on themselves, or perhaps ducked down and got wet. Very few of them were swimming, partly because it was unseemly, but mostly because most of them didn’t know how to swim, anyway. Besides, a woman’s swimming ensemble had so much fabric; she could barely swim if she tried.

After taking a dip, people changed back into their street clothes and walked along the beach, and wined and dined in the upscale restaurants. The hotel, as well as the other accommodations in the area were expensive, and were decades away from the “everyman” amusement parks and beaches to come. By this time, railroad man Austin Corbin, who had been a guest at Engelman’s hotel, decided to build the largest and grandest upscale resort hotel anyone had ever seen.

He bought his own chunk of beachfront and called it “Manhattan Beach,” hoping to attract his upscale clients by referring to their home island. He built a massive 700 foot long wooden hotel that could accommodate 150 guests in splendor, along with restaurants and shops inside. Former President Ulysses S. Grant was at the grand opening, and the famous band director John Phillip Sousa was on hand with the entertainment. To make sure people could get to his Manhattan Beach Hotel, Corbin, who was president of the Long Island Railroad, had a train line built that let customers off practically on the porch.

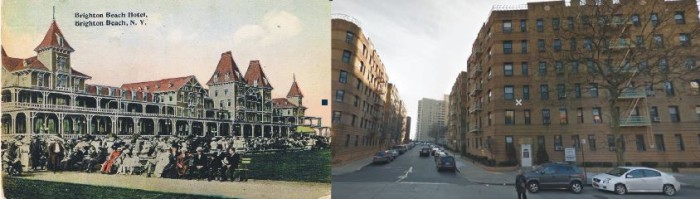

Well, Engelman wasn’t going to be upstaged. He and a group of investors built the Hotel Brighton, later called the Brighton Beach Hotel. It was bigger than the Manhattan Beach Hotel, and could accommodate almost 5,000 people; most of whom came for the day and ate in the restaurants, shopped, or used the Hotel’s other amenities. The hotel opened in 1878, and was also a splendid multi-story wood-framed hotel, with deep verandahs, towers, and manicured lawns, overlooking the boardwalk and the ocean.

Of course, sitting around looking at the water, occasionally wading in, and wining and dining is fun, but not that much fun, especially not for the men. They needed more, and in 1879, Engelman gave them what they wanted, a racetrack. The Brighton Beach Racetrack was the first of three horse racing tracks in the area, making Gravesend the racing capital of the country, with betting going on, big time. The tracks brought more people to all of the hotels, and the beach resorts became a preferred summer destination for many; much closer to home, and easier to get to than the Jersey Shore or Newport, Rhode Island.

Engelman wanted to give his guests as much to do as possible. In addition to the racetrack, he built the Brighton Theater and the Brighton Music Hall, both near the hotel. The theater featured the best vaudeville acts from the major vaudeville circuits. The Music Hall featured popular performers, such as Sophie Tucker and her band, and marching bands and other entertainment. The Bathing Pavilion also provided entertainment with games, human oddities, and other entertainments.

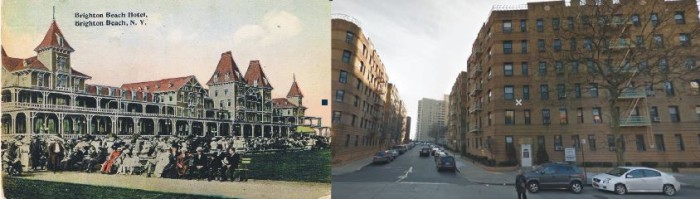

William Engelman died in 1884, but his son, also William, took over. Ten years after his father had built the Brighton Beach Hotel; his son realized it was too close to the water. The ocean was eroding the beach, and was almost lapping at the front porch. In a bold move that was costly, but highly publicized, Engelman had the entire enormous building raised up on tracks and moved further inland. 120 railroad cars were used to support the hotel, and three pairs of double engines slowly pulled the building 600 feet inland. It took over three months, but they did it, and the hotel was saved. Not even a window pane was broken.

But as cool as all of this was, it wasn’t to last. Over in nearby Coney Island, the “people’s Riviera” was building up with amusement parks and lots of people. Too many people for the elite’s tastes, they were starting to spill over into their territory. Development was also eroding the beach areas as surely as the ocean, as homes and cheaper hotels began to spring up. But that’s not what killed the grand hotels. In 1908, laws were passed prohibiting betting at the racetracks. In no time, the grand hotels started losing customers, and closed down, and eventually were torn down.

The horse tracks were turned into automobile raceways, and for a time did well, especially those patronized by such wealthy gadabouts as William K. Vanderbilt, grandson of Cornelius. But in time, they too closed, and the land was developed for housing. Soon after the hotels disappeared, and building began, developers began building small vacation bungalows on the site, but land was soon too valuable to keep those there. Apartment buildings began going up. The earliest families in the new Brighton Beach were Jewish immigrants escaping the Lower East Side. They filled the apartment buildings and bungalows, and one of the last remnants of old Brighton Beach, the Brighton Beach Music Hall, became a very famous and important Yiddish Theater in 1918.

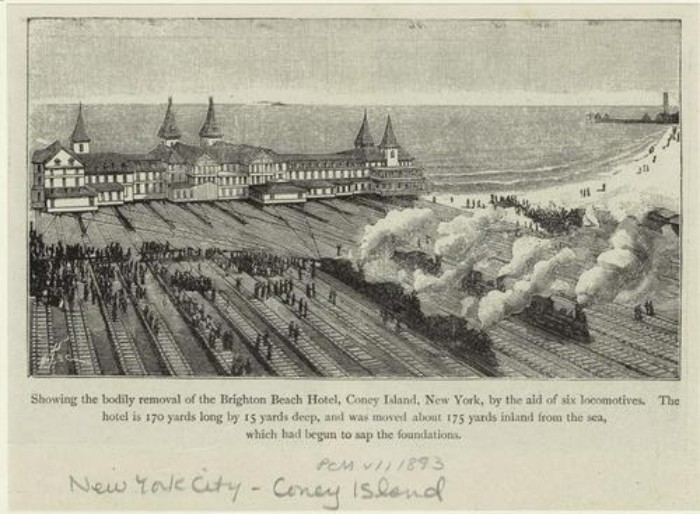

By the 1930s, all traces of the resort hotels, the racetracks, the bathing pavilions, restaurants and everything else was gone, all replaced by large apartment buildings that stretched from one end of the beach to the other. One complex, called Brighton Beach Gardens was built on the old hotel site. This massive complex covered where the hotel once stood, as well as the midway, music hall, and subsequent bungalows. This complex was the setting and backdrop of Neil Simon’s “Brighton Beach Memoirs.” The neighborhood remained predominantly Jewish until World War II.

By the 60s and 70s, the neighborhood had gone far downhill, as the middle class got out of the city, and many of the buildings were used for low income housing. Many buildings were abandoned or allowed to deteriorate. In the 1980s, immigration restrictions were changed, allowing thousands of Russian Jews and other people from the Soviet Union to come to America. Brighton Beach became home to most of them, changing again, and growing and improving. Today it is the largest Russian speaking community outside of Russia. English may not be the dominant language here in many places, but the ocean and it’s welcoming beach remain, as always.

The Brooklyn Beach front was very upscale 130 years ago it seems… Very different place today