Past and Present: Dedicating Grant’s Statue

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. The Civil War was tearing the nation apart in the 1860s. A group of influential men in New York City joined together to form the Union League Club, to support the Union Cause. They raised money for medicines and medical supplies for the troops, and rallied generally, for…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

The Civil War was tearing the nation apart in the 1860s. A group of influential men in New York City joined together to form the Union League Club, to support the Union Cause. They raised money for medicines and medical supplies for the troops, and rallied generally, for a strong Union identity and support for the country. The organization was formed by, and for the city’s elite. George Templeton Strong and Frederick Law Olmsted were two of the founding members. They believed that a strong union was important for business stability and profit, and also believed that it was the duty of the elite upper class to lead in civic responsibility.

The Club was a fascinating organization, with some ideas that would keep conspiracy theorists happy, but they also were quite bold and brave in their commitment to the Union, and to civil rights. They supported several regiments of colored troops, and after the war, were key figures in black political representation during Reconstruction. They were very civic minded and sponsored social and civic programs. The New York City branch of the Union League Club was key to the founding of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the building of the Statue of Liberty, and Grant’s Tomb.

The Brooklyn branch of the Union League Club was originally in the Heights, but soon grew to the point where they needed a much larger clubhouse, and there was no room left in the Heights to build. The new and upscale neighborhoods of Park Slope and Bedford had possibilities, and much of their membership was moving to both of these neighborhoods, drawn by fine housing stock, and good public transportation. A large plot of land was secured in Bedford, at an advantageous spot, the intersection of three important thoroughfares; Bedford, Rogers and Atlantic Avenue.

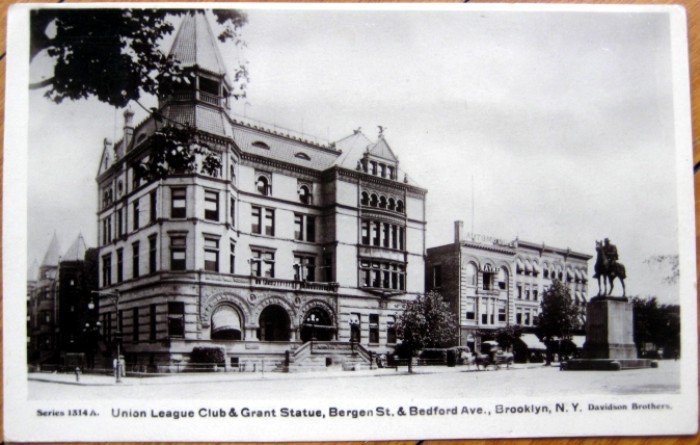

The Union League chose Peter J. Lauritzen, a Danish-born architect, to design the club. Lauritzen was well acquainted the city’s powerbrokers, and had designed homes for quite a few of them, as well as the Offerman Building and Smith-Gray & Co. buildings for two of Brooklyn’s most successful merchants. He designed an impressive clubhouse for the League, one that commanded the corner of Bedford Avenue and Dean Street. It was a large Romanesque Revival five story building with a tall tower on the corner. An observation deck was built on top, where one could look out and see much of Brooklyn, as well as Manhattan in the distance. Overseeing one’s kingdom, as it were.

The building had its own power plant and generator, and was lit by electricity, the first self-sustaining building in the neighborhood. It had a large ballroom, a library, meeting rooms, club rooms, game rooms, a billiard room, dining room and kitchen, and in the basement, a bowling alley and rifle range. The building was made of light colored brick with heavy brownstone trim, and a lot of terra cotta ornament. One would have no doubt as to the political or patriotic nature of the building, as it had a large oriel bump out supported by a huge eagle, with eagles perched on the roof, American flag shields held by heraldic bears, also on the roof, and the topper, two very well executed busts of Lincoln and Grant in elaborate roundels above the entrance of the building.

By the beginning of the 1870s, the Republican Party had Brooklyn well under control, and it did not let go of it until almost the turn of the century. With very few notable exceptions, the ruling elite of the city were all Republicans. Wealthy merchants, industrialists, financiers, lawyers, city officials, even architects, were all staunch Republicans. These men needed a secure place to do business, have meetings and political rallies, and generally get away from their wives and families, and sit around drinking, eating, smoking fine cigars and schmoozing with each other. More business deals were cemented here than in any boardroom or office.

By the 1890s, Bedford had grown and prospered. Fine row houses were going up all around the club, especially on Dean Street. NY State was building an impressive new armory down the block for the elite 23rd Regiment, and between the armory and the Union League Club, this part of Bedford was becoming a posh civic square. They would be joined by the headquarters for the Medical Society of the County of Kings, on Bedford, opposite the Armory, and the headquarters for the popular Kings County Wheelmen, an upper class bicycle club, right next door to the Union League Club.

The club decided the emerging square needed a large monument to the success of the Union and one of its heroes, General and President Ulysses S. Grant. They commissioned William Ordway Partridge to sculpt a heroic statue of Grant on his horse, which would commemorate the man and the victory of the Union. Partridge was one of America’s finest sculptors, and many of his works are part of New York City’s landscape, including statues of Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Samuel Tilden and more. Here he came through with one of his finest works, a large equestrian statue of Grant that captures not only the heroic aspect of the General, but also the humanity of the man, a battle-weary warrior resolutely facing the future.

The statue was placed on a large broad granite base and installed in the triangle formed by the intersection of Rogers and Bedford Avenues, with Bergen Street closing off the triangle. Grant faces the 23rd Regiment Armory, fittingly, and also has quite a view of Manhattan, and the future of the city. By the time the statue was dedicated, in 1896, plans for the unification of New York City were already in motion, plans backed by most of the members of the club, although ironically, they would mean the downfall of this particular branch of the Union League Club.

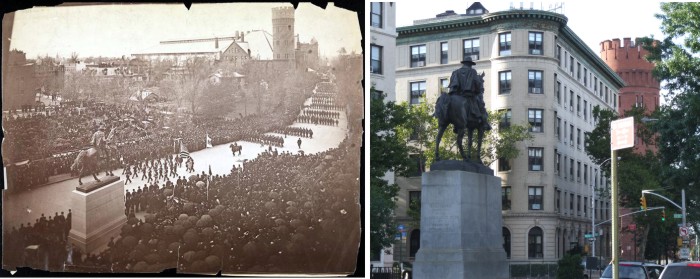

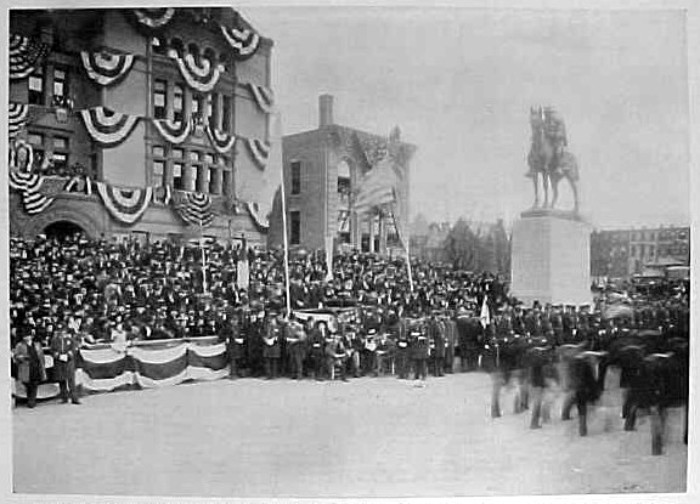

At any rate, the statue of General Grant was occasion for much pomp and splendor. It also caused the renaming of the plaza to Grant Square, now a part of the new St. Marks District, one of Brooklyn’s wealthiest neighborhoods. The statue was put into place in April of 1896, and the grand dedication was planned for April 25th, 1896. The photograph on the left records that ceremony.

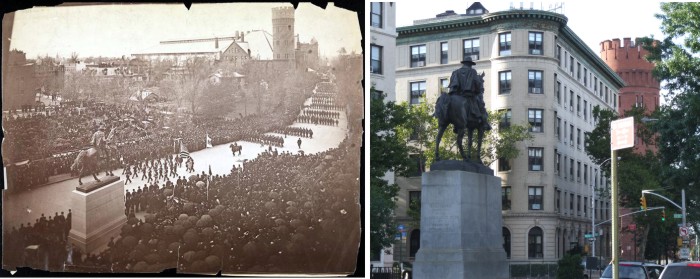

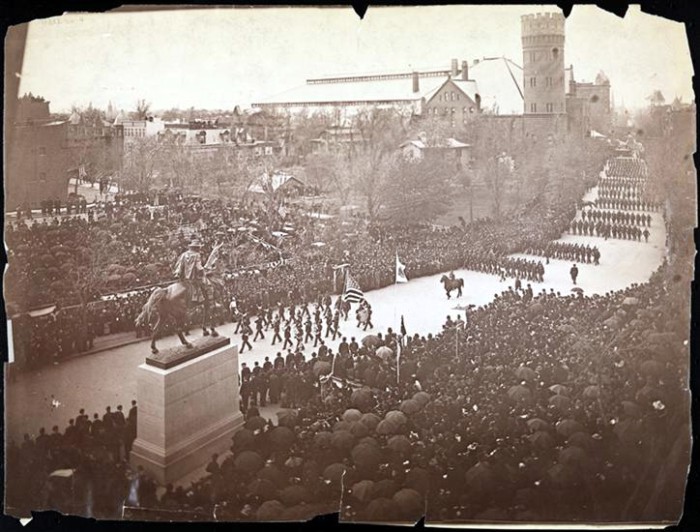

Apparently, it rained that day, to everyone’s disappointment, but that didn’t stop the pomp and ceremony. According to the Brooklyn Eagle, in addition to the local elected officials, the parade included several officials from Washington, representatives of the Army, and of course, the 23rd Regiment, and other Brooklyn National Guard units. The parade was led by a contingent of the Brooklyn Riding and Driving Club, the elite equestrian club in Park Slope, whose members were among Brooklyn’s wealthiest and most influential people. It also included a lot of retired military personnel, most of whom had done quite well in the private sector.

The parade marched south down Bedford, towards Flatbush, which is opposite the direction of traffic today. The reviewing stand behind the statue held Gov. Levi P. Morton, Mayor Frederick W. Wurster of Brooklyn, Mayor William A. Strong of New York, several generals from Washington, and the young grandson of Ulysses F. Grant, who would pull the covering from the statue after the dedication speeches.

The Union League Club itself was covered in red, white, and blue bunting, and was almost invisible behind the crowds of people who turned out for the parade. The papers said that there was much ceremonial splendor, with burnished sabers, fancy dress uniforms, and general military panoply. There was a musical program; there were lots of speeches hailing the deeds of General and President Grant. The rain lessened, and as just as young Ulysses pulled the strings that uncovered the statue, the rain stopped. The General faced the future, the troops and military bands marched past, and 1,500 of Brooklyn’s elite and their guests went into the Union League Club and had a great time.

The statue is still there, and in great shape. The photograph is interesting in that the Chatelaine Hotel, Montrose Morris’ last great building on the opposite corner of Dean and Bedford, is still a large private homestead. Today the large hotel building takes up that entire plot. Across Dean, the apartment building that stands there today was still an empty lot, and here, was part of the reviewing stand. The new 23rd Regiment Armory, only just completed the year before stands proudly. The photograph was probably taken from a window of the Union League Club. The vantage point is wrong for it to have been taken from the observatory tower. It’s a great shot showing the development of what is now Crown Heights North. GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment