Past and Present: Bethany Deaconess Hospital

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. As communities grow, so too does the need for community services. As has been stated here many times, Bushwick’s large German community began growing here in the 1850s, as nationalistic efforts to unify the many German city-states into one country turned into a bloody civil war, causing thousands…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

As communities grow, so too does the need for community services. As has been stated here many times, Bushwick’s large German community began growing here in the 1850s, as nationalistic efforts to unify the many German city-states into one country turned into a bloody civil war, causing thousands to pick up everything and move to America. The Germans were an immigrant success story, quickly establishing themselves in Manhattan, Brooklyn and elsewhere as very self-sufficient communities, with homes, industries, banks, schools, and religious and cultural institutions. From there, they integrated themselves into the rest of society. As their population in Bushwick grew, towards the end of the 19th century, they spread out from the Bushwick Avenue area, moving to Eastern Bedford, Ridgewood and East New York.

Religiously speaking, most of the Germans in Brooklyn were Catholic, Lutheran, or Jewish. Other Protestant denominations began courting the German immigrants, and by the turn of the 20th century, there was a growing population of German Methodists. The Methodist Episcopal Church in America, (not to be confused with the American branch of the Anglican Church; the Episcopalians) has a long history of social service, establishing old age homes, orphanages and hospitals across the country. They saw the need for a hospital in Bushwick’s German community, and the Eastern German Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church founded the Bethany Deaconess Society in 1900.

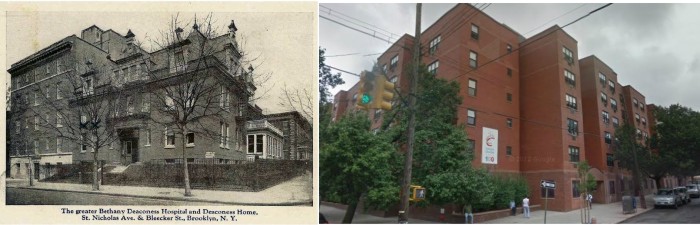

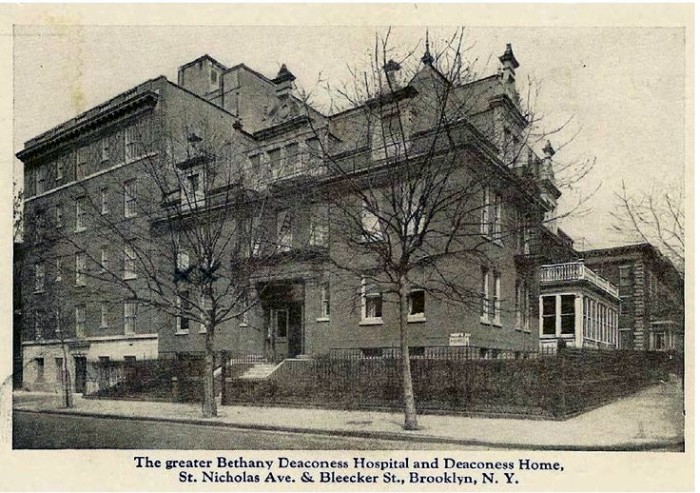

They began raising money from Methodists across New York and New Jersey to build a hospital here in the Wyckoff Heights section of Bushwick. Land was purchased from Peter Wyckoff, a descendent of the Dutch Wyckoff family that had once been one of Bushwick’s largest land owners. The new private hospital would be run and mostly staffed by the Deaconess Society, analogous to the orders of Catholic nursing sisters, who dedicated their lives to helping others through prayer and service in health care. In this growing community, the need for health care, especially maternity care, was great. These Deaconesses, who lived in nurse’s housing on the hospital campus, would stay with the hospital until the end.

In September of 1902, the main building of the hospital opened, and soon proved too small. Over the next sixty years, the hospital complex grew, until it consisted of eleven buildings. the Deaconess’ home was built in 1906, followed by other buildings, the last being a seven story general hospital building constructed in the 1960s. By the time the hospital closed in 1974, it had increased its bed space from 34 to 102. The hospital was located at 237 St. Nicholas Avenue, or 415 Bleeker Street, today.

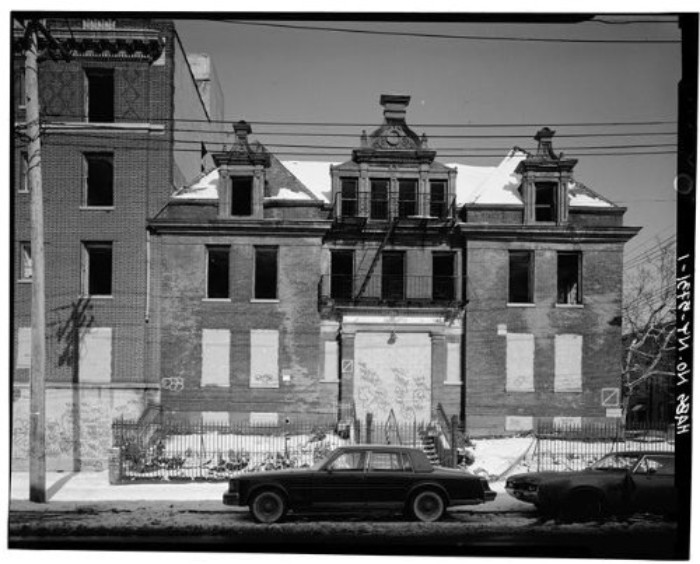

The main building of Deaconess was designed by John Boese, a local architect with offices in Manhattan and Long Island City. He is on record for designing three churches in the metropolitan area, but little else is known about him. This building, designed in the German Renaissance style, was unique in Brooklyn, with a distinctive roofline, with seven Dutch gable dormers. The wrought iron on the building’s balconies and stairways came from local ironmongers in Bushwick, and the building was built by the same contractors who were busy building nearby Ridgewood, Queens. As the hospital grew, so did the neighborhood of Wyckoff Heights. Modest, unadorned two family row houses and small apartment buildings dominate the area, all built in the first decades of the 20th century.

In 1966, the entire hospital site was sold to nearby Wyckoff Heights Hospital. They continued to operate it as the “Bethany Pavilion,” which housed non-surgical patients, out-patient facilities, laboratories and offices, until 1974, when they closed the whole thing down and walked away. In the eleven years that followed, the entire complex was vandalized and looted, with scavengers taking out all of the pipes, fixtures, wrought iron balconies, bannisters, doors, woodwork and anything else of value, while vandals repeatedly trashed the place, destroying whatever was left. At last, the buildings were sealed in concrete, and the site was sold to Catholic Charities, who tore the hospital complex down in 1985 to build the Sister Lucian Lucchi CSJ Senior Citizen’s Apartments.

Fortunately, before the hospital was torn down in 1885, an extensive study was done by an architectural historian working with the National Park Service, sponsored by Catholic Charities. This study cataloged the site, researched its history, and most importantly, took black and white photographs of the buildings, especially the original German Renaissance style structure. That report is the source for this article, and some of those photographs are reprinted here.

If you are interested in seeing more, especially if you like deteriorating urban buildings, the entire collection from the 1985 survey is available to view here. Many other hospital complexes find new use as apartments in other parts of the city. Look at the success of Jewish Hospital in Crown Heights. It’s too bad these buildings are allowed to be destroyed by the elements and people before they can be rehabbed. The walls, ceilings and floors of this hospital, even in its deteriorated state eleven years after being abandoned and stripped, were strong, laced with iron beams, the foundation walls were two feet thick. These were good buildings. GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment