A History of Brooklyn's Extravagant, Soon-to-Be-Restored Paramount Theatre

Brooklyn, one building at a time. The Brooklyn Paramount Theatre was one of Brooklyn’s famed movie palaces. Like most of the great movie palaces built in the 1920s and ’30s, the Paramount was ornate and over the top. It’s now on its way to being restored, but it was almost lost forever. Here’s a look…

Brooklyn Paramount Theatre in 1948 via Long Island University

Brooklyn, one building at a time.

The Brooklyn Paramount Theatre was one of Brooklyn’s famed movie palaces. Like most of the great movie palaces built in the 1920s and ’30s, the Paramount was ornate and over the top. It’s now on its way to being restored, but it was almost lost forever. Here’s a look at its early days.

Name: Brooklyn Paramount Theatre

Address: 385 Flatbush Avenue Extension

Cross Streets: Corner of DeKalb Avenue

Neighborhood: Downtown Brooklyn

Year Built: 1928

Architectural Style: Very simplified Art Deco office building

Architect: Rapp & Rapp

Other Works by Architect: Loew’s Kings Theatre in Flatbush, Paramount Theater in Times Square, and numerous theaters in Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis and other large cities

Landmarked: No

The Brooklyn Paramount Theatre was the last of Downtown Brooklyn’s great theater palaces to be built. By 1930, back in the days when people got dressed up to go to the movies, the borough’s moviegoers had a choice of five enormous theaters to attend, each holding thousands of people.

The Paramount, Metropolitan, Albee, Fox and Strand theaters were all only blocks away from one another. Perhaps that was why this theater, although one of the most ornate, was never quite as popular as some of the others.

It was built by Paramount Pictures, as was its sister theater in Manhattan. Both were designed by the Chicago-based architectural firm Rapp & Rapp, which specialized in theaters.

Rapp & Rapp designed one of their most fantastic and ornate theaters here, hidden behind the plain façade of a nondescript office building. Aside from the theater’s marquee and a large sign towering above the building, one would never know that wonders were inside.

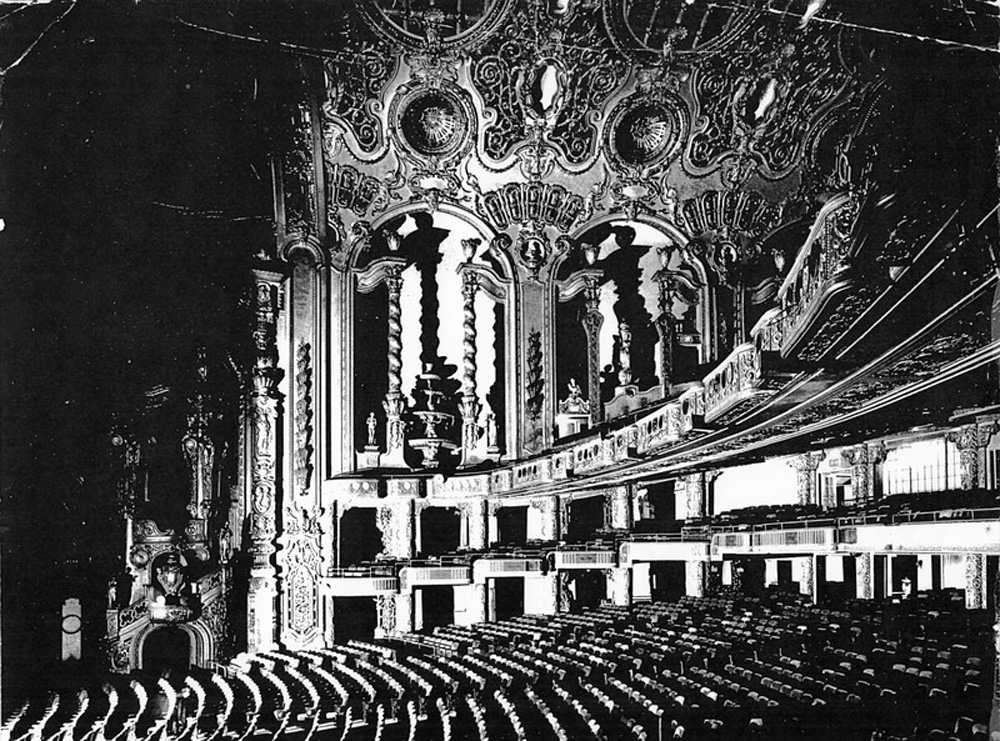

Brooklyn Paramount Theatre interior in 1928. Photo via Cinema Treasures

A Depression-Era Escape Into Exotic Splendor

Like all the huge movie palaces of the day, the Paramount allowed audience members to escape from their worries and everyday concerns, and luxuriate in the opulence of a fantasy world.

The lobby was spacious, with an ornate vaulted ceiling three stories above. The hallway was lined with large columns on both sides. The floor was marble, and the balconies on the mezzanine were lined with detailed wrought-iron balconies and grilles.

Originally, long velvet draperies, elaborately festooned and swagged, were hung in the arched openings. It was impressive, but nowhere near as impressive as the theater itself.

1928 photo via NYCAGO

The grand old movie palaces had many architectural influences. Some architects created an exotic Moorish/Oriental/Hollywood world. Others referenced the Baroque period, using that time period’s penchant for over-the-top ornamentation as a starting point.

Rapp & Rapp went for full-blown Baroque. They covered every inch of the theater space with ornate plaster decoration, most of it gilded and gleaming. The ceiling was a special treasure, as were the box seats and the stage. There were hidden archways, with urns and painted ceilings, and lit scrims with garden scenes, giving one the feeling of a French palace in the mid-18th century.

Even the restrooms were overdone, with marble fountains and fancy sinks. The entire place was lit with soft Deco-style lighting, and draperies were everywhere.

Brooklyn Paramount interior in 1937. Photo via Long Island University

Live Performances at the Brooklyn Paramount

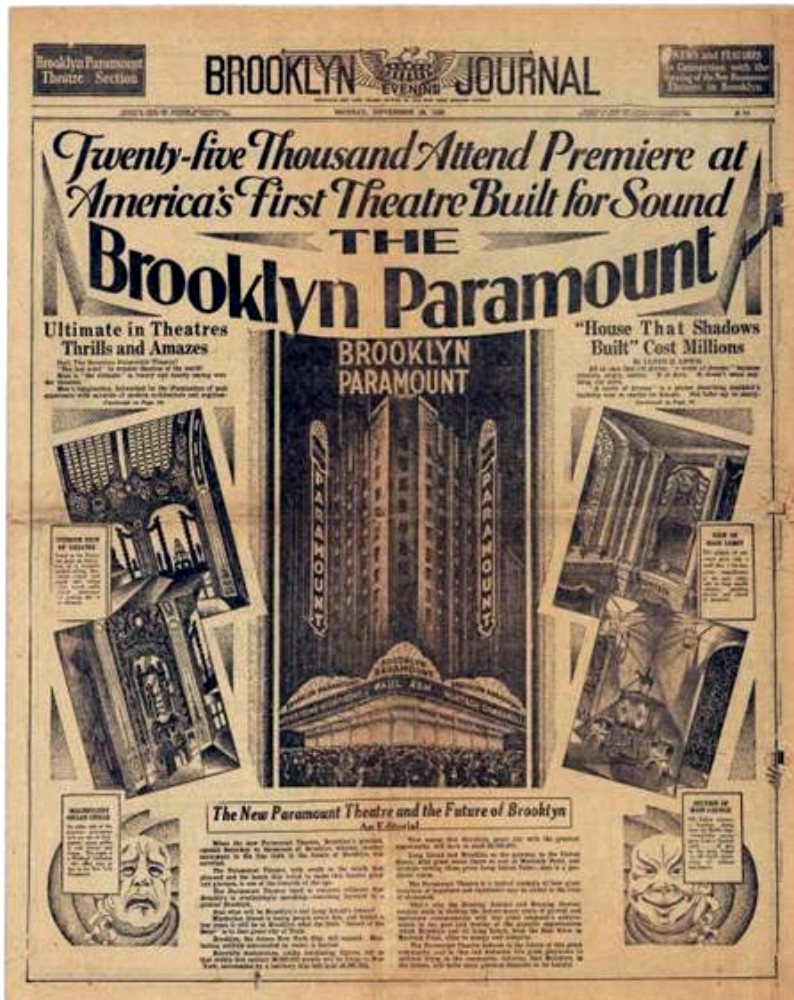

The Brooklyn Paramount opened on November 24, 1928, with Manhattan Cocktail, a silent film with sound effects, as well as a 10-act variety show featuring vaudeville star Eddie Cantor and many other performers.

It was one of the largest, with 4,124 seats. Its main rival, the Fox Theatre, on Nevins and Flatbush, had 4,305 seats, topped only by Manhattan’s Radio City Music Hall. But in spite of the theater’s opulence, it was never as successful as the others nearby.

Wurlitzer organ photo by Ken Roe for Cinema Treasures

The Paramount, like most theaters, had a full stage and orchestra pit in addition to a large movie screen. One of the theater’s highlights was a huge twin console, four-manual, 26-rank Wurlitzer organ, one of only two of its model. The organ has 2,000 pipes and 257 stops. Its massive pipe system could rattle the building with great magnificence. Miraculously, it’s still there, and has been well maintained and in use.

The theater helped introduce jazz to a Brooklyn audience in a big way, featuring Duke Ellington and his orchestra in 1931. It also introduced Yiddish music in 1943. But the theater is best remembered for hosting 1950s rock ‘n’ roll concerts, featuring the likes of Chuck Berry, Fats Domino and Buddy Holly.

1950s photo via Cinema Treasures

DJ Clay Cole broke house records with a big-name holiday concert starring Ray Charles, Bobby Rydell, Brenda Lee, Neil Sedaka, Bobby Vinton, Bo Diddley, Chubby Checker, the Drifters, the Shirelles and many more.

The last live show at the Brooklyn Paramount was Clay Cole’s Easter Parade of Stars starring Jackie Wilson and an all-star cast in 1961. The last movie, Hatari starring John Wayne, was shown a year later, with only 300 people in the theater on opening night.

1928 opening day press via Brooklyn Rail

The Fate and Future of the Brooklyn Paramount

Long Island University had already purchased the building in 1950, with some of its classrooms and offices had been in the office block of the large building as the theater was still operating, and in the early ’60s the college decided to use the theater, as well.

They removed the marquee, roof and blade signage, and placed a new entrance into the building. The lobby was transformed into a student canteen. The lounges in the basement, once ornate and plush, were transformed into office and meeting spaces.

The auditorium itself underwent the biggest transformation. The orchestra floor was leveled and made into a basketball court. The mezzanine and loge levels were removed. The rear balcony was closed off for office space. But the ornate ceiling, the side walls and some of the stage remained more or less intact.

They also saved the organ. It always had the ability to rise up out of the orchestra pit, and it still did, used during basketball games to great and impressive effect. It remains one of the most impressive and best instruments of its kind in the world.

Considering that many new tenants would have simply ripped everything out, LIU did a magnificent job of preserving the theater’s grand history, while repurposing it for school use. It reopened in 1962 as the Harold and Marie Schwartz Athletic Center.

The Paramount Theatre as LIU’s basketball court. Photo via NYCAGO

The theater remained a hidden treasure. The building was renamed Metcalfe Hall after the University’s first president, Tristram Walter Metcalfe. In 2005, the school’s basketball team, the LIU Blackbirds, moved to a new athletic center, and aside from occasional events, the old Paramount was not in use.

In April of 2015, LIU announced that the theater had a new 49-year lease to Paramount Events Center, a partnership headed by Barclays Center developer Bruce Ratner, Barclays Center CEO Brett Yormark, and Onexim Sports and Entertainment, the company owned by Barclays and Brooklyn Nets co-owner Mikhail Prokhorov.

Rendering by H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture via Long Island University

Architect Hugh Hardy and his firm will be recreating the auditorium, which will become a venue for concerts and other live events. They plan to keep and restore the original Rapp & Rapp details, while adapting it for modern use.

The transformation is expected to cost at least $50 million and take two or three years.

It’s great news for theater preservationists — first the Loew’s Kings Theatre in Flatbush was restored, and now the Brooklyn Paramount will join it.

A wonderful essay featuring past and present-day photographs of the theater, with all of the remaining details and ornament, can be found at Scouting NY.

1930 postcard

Photo by Ken Roe for Cinema Treasures

Related Stories

Revamped Kings Theatre in Flatbush Sells to Ambassador Theater Chain

Walkabout: Brooklyn’s Fox Theatre, part 1

Walkabout: Brooklyn’s Fox Theatre, part 2

You are forgetting the Roxy Theater.

At the grand opening it was the largest movie palace in the world and was called “The Cathedral of the Motion Picture”

The Roxy in 1927 and Radio City Music Hall in 1932 both claimed to be the largest (5900 – 6200) depending on who was counting. Of course, since Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel was the first manager of the Roxy (the theater was named after him due to his reputation) and then became the first manager of Radio City Music Hall, boasts of which was the largest were always suspect.