Music, Beer, and Cigars: A Concert Garden Comes to Brooklyn

Successful Victorian entertainment venues had to pander to popular taste, as a self-made impresario quickly discovered.

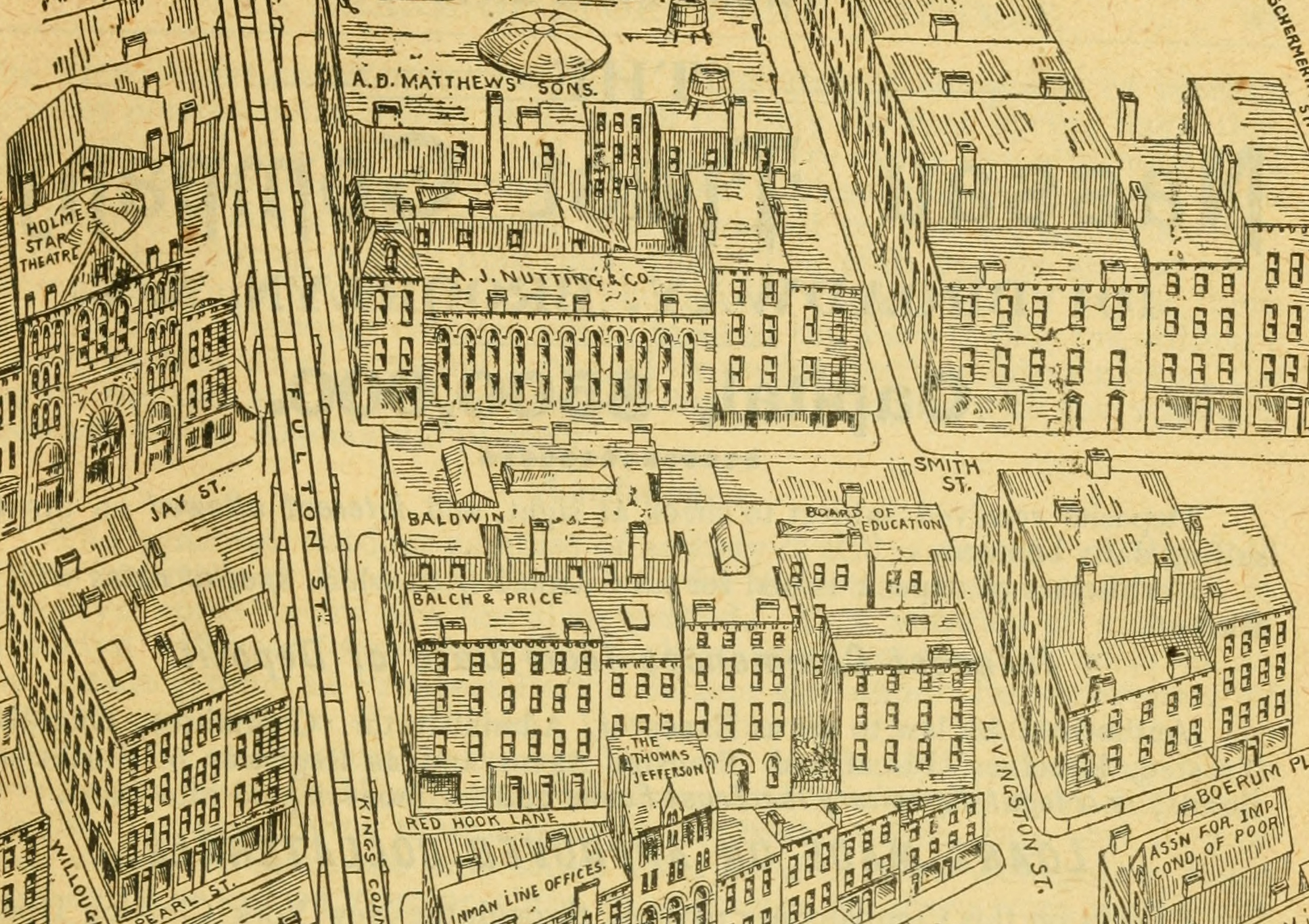

The corner of Fulton Street and Smith Street in Downtown Brooklyn was once home to a concert garden. Photo by Susan De Vries

The popular American concert gardens of the post-Civil War years owe their creation to the German beer garden and the English music hall. The music hall influence comes a bit later in our story. But first, Germany’s civil war between the different city-states was the impetus for thousands of Germans leaving and settling in the United States beginning in 1848. These immigrants came from every stratum of German society, and included manufacturers, merchants, and professional people.

Large German neighborhoods were established on the east side of Manhattan and the area in Brooklyn called the “Eastern District,” which included Bushwick and parts of Williamsburg and Bedford Stuyvesant. The new people brought their industries, culture, and customs with them. Our gymnasiums, kindergartens, and delicatessens had German origins, along with what is most important to our story – German-style breweries and lager beer.

Americans were used to brewing and drinking dark British-style ales and stouts. Making ale involves fermentation that takes place at the top of the barrel. German lager ferments on the bottom of the barrel and needs to be stored in a cool dark place during fermentation. The result is a lighter golden beer with a very different taste. Many different breweries were established in Brooklyn over the next half century, and some, like Ulmer’s, Trommer’s, and Liebmann Sons (Rheingold) became household names.

The Germans also brought their tradition of beer gardens with them to America. Many of the larger breweries established ones next to their complexes. Ideally, they consisted of a walled-in park landscaped with trees and foliage, with pathways winding around tables and chairs. Food and drink (beer!) were served, and a stage was set up for bands and performers. Trommer’s in Bushwick had one of the largest and most famous beer gardens. Entertainment, food, and drink in an outdoor, or semi-outdoor, location became all the rage.

Gilmore’s Concert Garden

In Manhattan, the king of mass entertainment and spectacle, P.T. Barnum, established his Great Roman Hippodrome on the site of an early railway complex at East 26th Street and Madison Avenue. Barnum’s Hippodrome opened in 1874. It was an open-air arena surrounded by covered bleachers, with circus and other grand-scale performances performed in the center, in a huge space that could be tented in inclement weather.

Barnum had a lot going on, so in 1876 he leased the space to popular bandleader Patrick Gilmore, who renamed it “Gilmore’s Concert Garden.” Gilmore was able to create something very much like a German beer garden – only with much more stuff.

The Brooklyn Daily Times noted that Gilmore’s Garden featured “fragrant evergreens and a garden with serpentine walks, beds and banks of flowers, statuary, rustic bowers and seats,” all illuminated by long rows of colored lights, making the garden like something one would read about in a fairytale. He even had a fountain and pool stocked with goldfish and turtles and a 30-foot-high cascading waterfall located near the main entrance.

Tables and chairs were scattered throughout, and private boxes were available. There was table service, and waiters offered all manner of ice cream, sweets, and desserts, as well as lager beer, soda, or lemonade. Gentlemen were encouraged to smoke their cigars without offending the ladies as the garden was kept cool and ventilated. As patrons enjoyed their treats, live entertainment took center stage.

Gilmore’s band had 100 players, all in uniform and led by Maestro Gilmore himself. The musical fare included band marches and themes, patriotic music, opera selections, music by Bach, Brahms, and other composers, and popular tunes. Gilmore always ended the evening with a rousing rendition of the “Star Spangled Banner.” Legendary band composer John Philip Sousa introduced some of his own music here.

Unfortunately, as Barnum could attest, audiences demand frequent change, and providers had to constantly come up with something new. In addition to band music, Gilmore tried all kinds of events and attractions, among which were minstrel shows, hosting the first Westminster Dog Show and the first large scale boxing matches. His choices of players and music changed to more popular fare, like working class British music halls, and the Concert Garden began to have a reputation for tawdriness and rowdies — not a place for proper ladies and gentlemen.

This did not go unnoticed over in Brooklyn. Another entertainment impresario thought the idea of a concert garden could be brought to Downtown Brooklyn, where it would appeal to a higher-class audience and be quite successful. His name was Alexander R. Samuells, and his idea for a classy new garden would be called the “Mozart Concert Garden.” The composer’s name signified an upscale environment.

Samuells was an old hand in the entertainment business. He was born in England in 1842 and was brought to the U.S. by his parents as an infant. During the Civil War he was a captain of the “Fighting 14th Regiment” out of Williamsburg and saw action in several key battles. After the war ended he returned to Brooklyn and went into the hospitality and entertainment business.

He ran Brooklyn’s Park Theater and a successful billiard parlor for several years. In the early 1870s he teamed up with Patrick Gilmore for the first international walking match at Gilmore’s Garden. According to his obituary, he made a lot of money on that one. Professional walking would be an idea he brought back later in his career.

It was Samuells’ experience with Gilmore’s Garden that inspired him to open his own establishment in Downtown Brooklyn. It would be smaller, but classier, with better décor, entertainment, and everything else, and would erase the bad taste people had for the frequent low-class doings which were now more prevalent in Manhattan.

The Mozart Concert Garden

The Brooklyn newspapers announced in the summer of 1877 that a new entertainment venue was coming to downtown in what was becoming an active theater district. The “Mozart Concert Garden” was styled after Gilmore’s Garden in Manhattan. The Brooklyn Standard Union reported that construction had begun on a brick building located at the southeast corner of Fulton and Smith streets, at 386 Fulton Street. The venue would have “flowers, shrubs, fountains, birds and fishes, and concerts employing good musical talent.”

The building was hastily thrown together in only two months. It was discovered years later that the only plan for the building was a penciled outline drawn on tissue paper that had no details and no measurements, only a sketch of the desired building. Opening night was a Saturday in August in 1877. So many people showed up that the Brooklyn Daily Times reporter called it an “uncomfortably large crowd.” He went on to note that the building itself wasn’t even finished.

The gallery had no railing, and couldn’t be used until finished, the room was unpainted, and the walls of the building had only been whitewashed. There were no frescoes or art of any kind on the walls. The floor was gravel and filled with tables and chairs which could seat up to 500 people.

The stage was set up on the only wall without windows. Samuells did try to liven the place up with a chandelier, some hanging baskets, and a clock. Flowers and plants surrounded the stage. Much more ornate and impressive décor was promised. One reviewer in the Brooklyn Eagle found the lack of interior distractions “refreshing in its simplicity and freedom from meretricious effect.” Captain Samuells just wanted a place, as the paper concluded, “where one could hear good music while drinking beer and smoking cigars.”

The beer served was brewed by Liebmann & Sons Brewery of Bushwick. They had an exclusive contract with the Garden. Liebmann’s lager, considered by many to be the finest of Brooklyn’s beers, was delivered from Bushwick in barrels.

Opening night was complete with musical entertainment designed to please just about every musical taste. The Eagle printed an ad with the musical program in advance of the opening. The band leader was respected composer and conductor Emil Seiferts, presiding over an orchestra of 40 and well-known soloists.

The Brooklyn Eagle reporter who wrote the paper’s opening night review was a harsh critic and a social snob. “The audience was as miscellaneous as the popular price of admission would lead one to expect.” he wrote. “Many ladies were present, most of them, however, being German.” The critic also wrote that he thought Maestro Seifert, his orchestra, and the choice of classical music were all very good and received a warm reception. But he also noted that most of the audience would have preferred popular music and responded much more enthusiastically to the familiar tunes.

The writer thought it almost impossible to have both the Philharmonic and the Music Hall on the same program. He certainly wasn’t the only one. This had been an issue for Gilmore’s and all the other concert gardens in both cities and would prove to be a problem that needed to be solved here as well.

Mozart Garden began hosting Sunday evening sacred concerts. These were met with great approval and enthusiasm by the classical music crowd. Those people were not the majority of patrons, however. Like any good entertainment impresario, Samuells soon turned to the old adage of “Give the customers what they want.” Only two weeks after opening night, Siefert and his orchestra were out of jobs, fired with much rancor and animosity on both sides.

A week later, the papers announced that Mozart Garden was rebranding itself as “Brooklyn’s London Music Hall.” The entertainment would include popular music, dancers, and other variety show acts, along with demonstrations of athletic prowess and skill. One acrobat act was labeled the “Tumbleronicon.” From there it didn’t take long for Mozart Garden to fall completely from grace like Gilmore’s and be branded a den of iniquity and vice, a place where no one decent would visit.

Tales were told to the papers of drunken bridegrooms celebrating at the Garden, large groups of rowdy young men who pounded on tables and made noise during the shows, and more. The Kings County Rural Gazette noted that “Mozart Garden has become so conspicuously disreputable, that the special surveillance of the police is ordered at the haunt of iniquity.”

The temperance movement was quite active then, and the Mozart Concert Garden became one of their biggest targets. Spies visited the place and reported back to the groups of the activities in this den of evil and drink. What did Samuells do? He rented out the hall for temperance meetings. They had a huge rally there in February of 1878 and met there on many other occasions.

But only a year into its existence, the Garden wasn’t doing all that well. Samuells was losing money rapidly. To up his customer base he stopped charging admission. In August 1878 he renovated the hall, making the stage larger and configuring it more like a concert hall than a beer garden. He added more acts and was constantly looking for something new and novel that would save the business. He found it in one of the most unusual acts of the late 19th century.

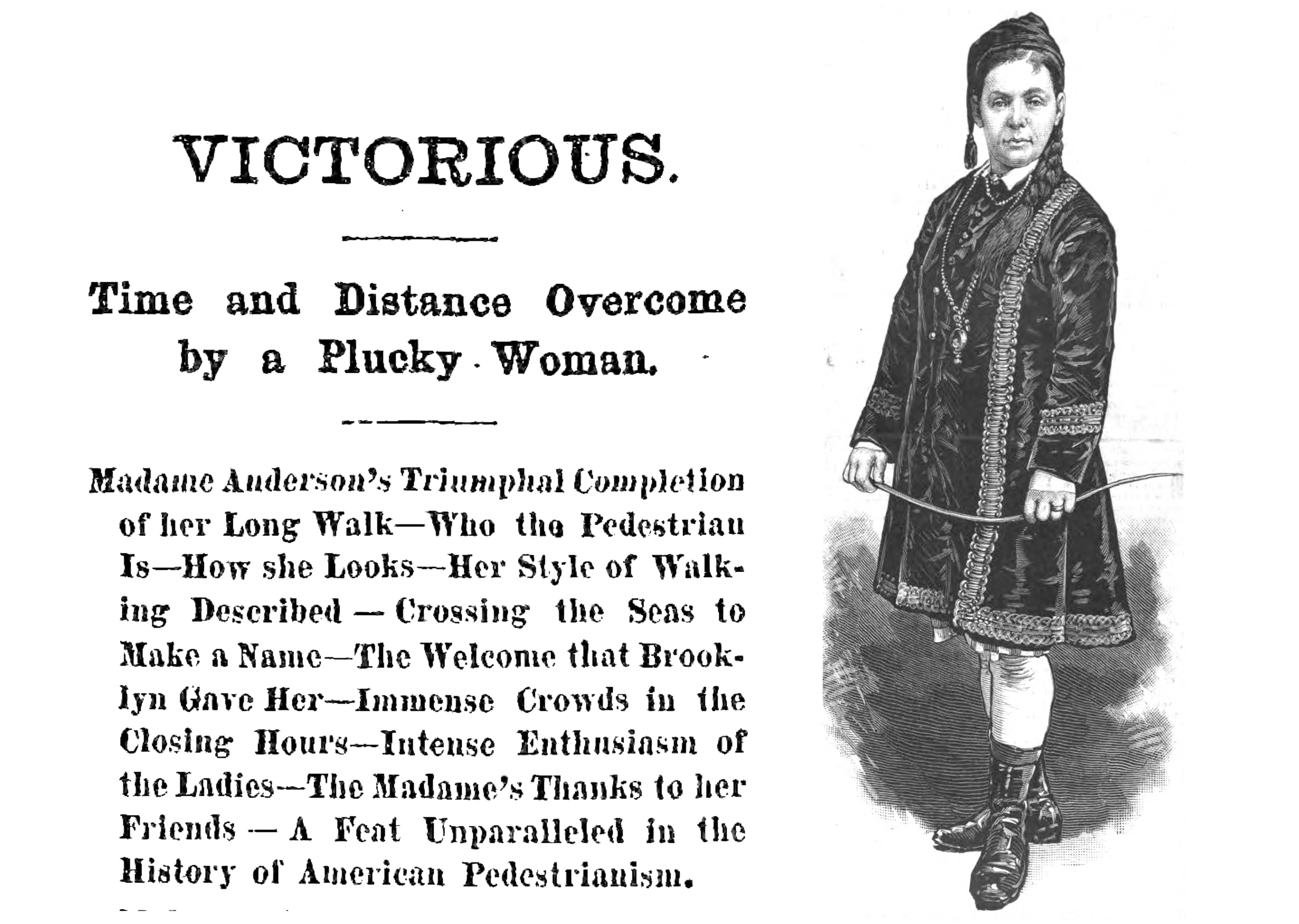

Madame Ada Anderson was a 36-year-old Englishwoman who had made a name for herself as a professional “pedestrian.” She walked for money. She was one of a handful of people, mostly male, who walked around an indoor track or cross-country for a predetermined number of miles within a certain timeframe. Patrons paid to watch them, encourage them and, no doubt, place bets under the table. Ada Anderson was the champion pedestrian in Europe when she accepted Samuells’ invitation to walk at the Mozart.

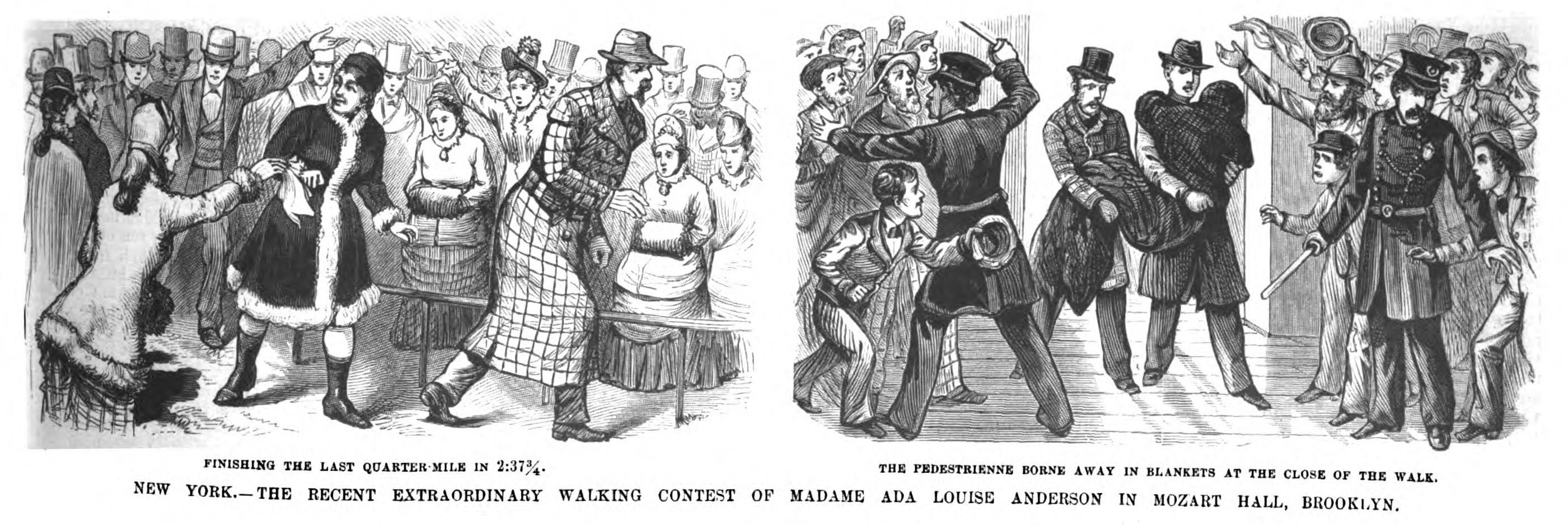

Madame Anderson planned to walk 2,700 quarter-miles in 2,700 consecutive quarter hours. That’s 675 miles in 675 hours, which was a record unheard of in the United States. The walk was going to take a month. In preparation for this event, Samuells tore out the stage and seating and turned the floor into a large oval track with a bucolic country lane and painted backdrops and props. Chairs were placed on the floor within the ring, with seats in the gallery and plenty of space for standing room.

The public paid 15 cents to enter the building to watch her walk. Children could attend for five cents. While they were there, lunch, tea, and other fare was available, but Samuells was not about to let this exhibition turn into some kind of raucous horse race. He encouraged families to attend. Madame Anderson began walking. A brass band played, and people cheered and shouted encouragement as she ticked off the quarter miles.

The Brooklyn Eagle noted that she stepped forth with a graceful easy and dignified movement, taking light steps. She swung her arms and smiled at the spectators. Everyone was sure she’d complete her task. During her 15-minute breaks she ate rare steak, and drank port wine, champagne, or tea.

Seven circuits around the track made up the quarter mile. She retired to the back of the house for her rest and sleep periods, which were only 15 minutes long as well. She emerged fresh for the next round of walking. She often changed her costumes, to the delight of the audience. At times she sang and entertained as she walked.

Madame Anderson’s walk was filling the house day after day. As the hours passed, the crowds grew. She was adored by her female audience who gathered to cheer her on throughout her walk. Samuells saw his profits rise. He cleared $14,000 in the first two weeks alone. She was tireless. Anderson walked consistently day and night, at times with swollen feet and exhaustion, but she persevered. As she neared the end of her walk, Samuells raised the price of admission from 25 cents to 50 cents per person. When she was about to reach the finish line, he raised it again, this time to $1, and $2 for a box seat.

Madame Anderson completed her extraordinary walk on January 13, 1879. When she crossed the finish line the place was so packed that people were standing in the streets. According to one account, she was paid $8,000 for her efforts, while Samuells netted around $34,000. He wanted to sign her on for another walk, but she got a better offer from someone else. There was ugly fighting and court action, but she never appeared with him again.

That money didn’t last long, and after the walk was over, Captain Samuells needed something new to make some money. He and a partner decided they would have what they called a “Zulu Exhibition” at Madison Square Garden. They put up a bunch of thatched huts, got a crowd of black men to dress up in what the sponsors thought was Zulu attire, and walk around the surrounding area with spears and clubs. It backfired completely, as people were frightened and stayed away. It was later revealed that the “authentic Zulus” were black Americans living in Lower Manhattan.

Boxing matches were next for Mozart Garden. Unfortunately, they were illegal at the time, so Samuells called them “Scientific Exhibitions,” where one could very scientifically examine the damage a fist hitting someone’s face would cause. These matches were one of the many attractions on a sports night with various other athletics, so they got away with it.

Captain Samuells threw himself entirely into his business to the detriment of his family. He and his wife had a contentious relationship, with abuse, alcohol problems, and infidelity ruining their lives. At one point, Mrs. Samuells was committed to an institution for inebriates, and their children were sent to a children’s home. When she got out, she filed for divorce, claiming cruelty and abandonment. He was required to pay alimony, and with his boom-and-bust financial situation, he fell way behind and had to be brought into court and ordered to pay.

The Mozart Concert Garden closed its doors permanently in 1879. Samuells moved on to become the manager of the popular Union Hotel at Coney Island. In 1892, his son, Alexander B. Samuells Jr., was found dead on the beach that summer. He had been shot in the temple, and a pistol was found in his hand. The verdict was suicide. He had recently married a woman of suspicious circumstances and morals who was at least 30 years older than he, and they were seen quarreling. Captain Samuells believed his son was murdered; especially since some of the details of the case did not make sense. He vowed to find out what really happened but never did.

His circumstances never really improved. He tried several other ventures that were unsuccessful. He ended up at the Soldier’s Home in Bath, New York, where he lived for several years. He came back to Brooklyn for a while, and friends thought he looked to be in good spirits. However, he was ill and died on October 17, 1913. He’s buried in Trinity Cemetery in upper Manhattan. Over the course of his life, he made and lost over a quarter of a million dollars.

After Mozart Concert Garden closed for good, Brooklyn Opera House took over and redid the building in 1879. Then the building was purchased by the department store A.J. Nutting. The firm reconfigured the building for retail, added the plot next door, and remained there into the 20th century. Plans to demolish the building and replace it with a three-story candy factory were announced in 1925. It was then that the lack of plans for the Mozart Concert Gardens building was discovered.

“If there hadn’t been real builders in those days, Nutting’s building would never have stood the wear and tear as long as it did,” reported the Brooklyn Daily Times. The Schrafft’s Candy Company building, designed in the new Art Deco style, still stands on the corner of Adams and Fulton streets. The Mozart Concert Garden, its owner, and activities are now just a footnote in the greater story of Brooklyn.

Author’s note: Thanks to historian and new friend Derek Hoff for bringing Samuells to my attention. Derek learned of Samuells and his Mozart Concert Garden while researching the book he is writing on the history of Bushwick’s Rheingold beer and the Liebmann family that owned it. If someone you know once worked at the brewery in Bushwick and you would like to help Derek out with his research, please get in touch by commenting below or emailing tips@brownstoner.com.

Related Stories

- Living on Atlantic Avenue, the ‘Spine of Central Brooklyn’

- From Mansions to Housing for Navy Yard Workers: The Clinton Hill Co-ops Story

- The Sweet Life: A History of Candy Making in Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

Excellent article. Very interesting. So many interesting maps of how it was back then. Thanks so much!

Someone needs to bring it back!!

lol!