How Charles Pratt's Morris Building Company Beautified Brooklyn

Well built, artistic, and useful, the company’s buildings were the fruit of longtime partnerships with some of the most talented architects of the day.

A townhouse at 181 St. James Place in Clinton Hill was built by the Morris Building Company. Photo by Susan De Vries

A side project of the richest man in Brooklyn in the 19th century, the Morris Building Company developed some of the borough’s most artistic and important buildings. Notable examples include English Arts and Crafts-style row houses, worker housing ahead of its time, and most of the original Pratt Institute buildings. At turns whimsical and utopian, with quality always foremost, the designs were the fruit of longtime partnerships with some of the most talented architects of the day.

How It All Began

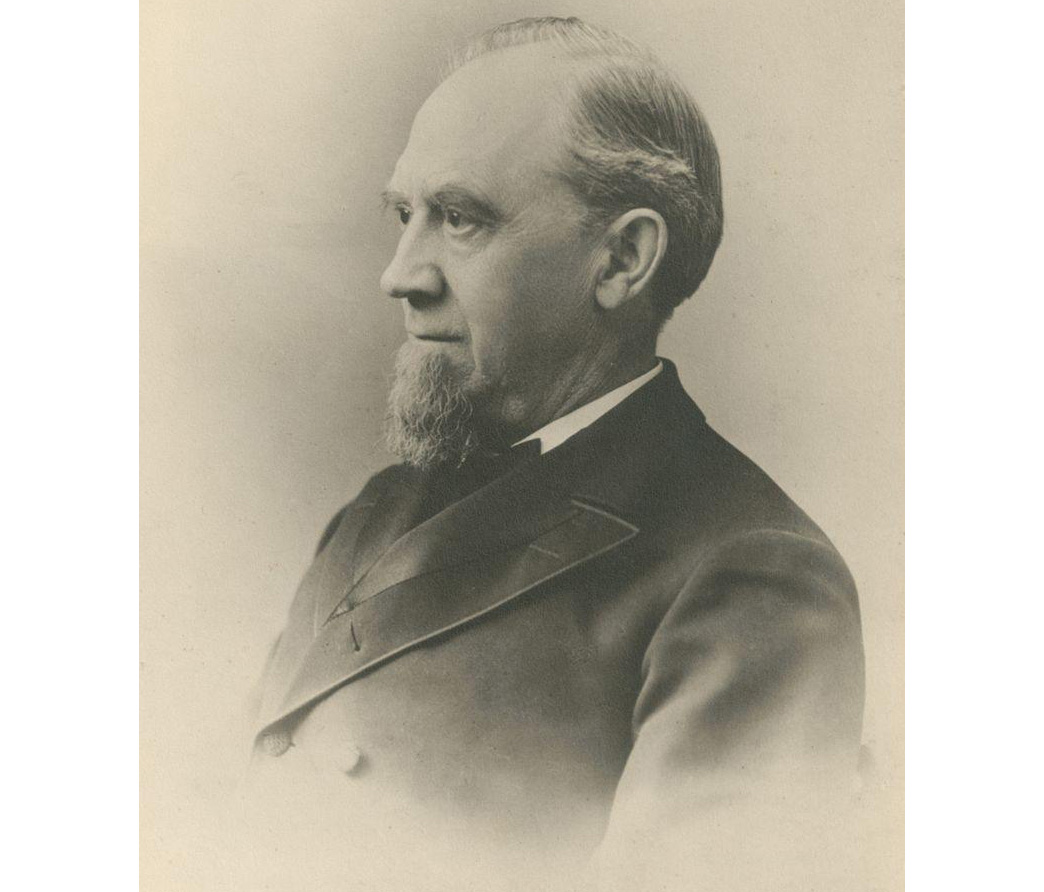

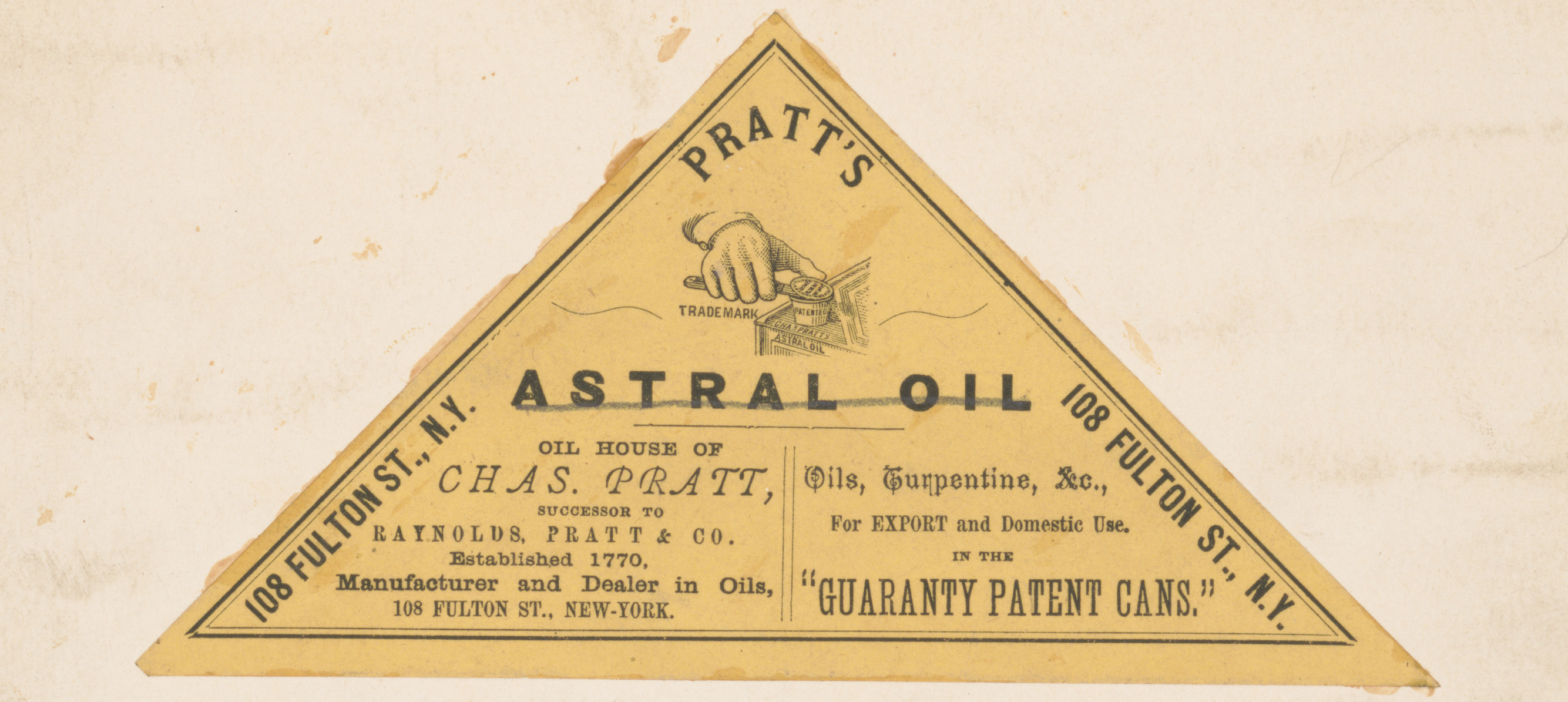

Charles Pratt was an oil man. He made his fortune in petroleum refining and production. He and his partner Henry Rogers established an oil refinery along Newtown Creek in Greenpoint that was unrivaled for its time. The refinery produced several oil-based products, the most well-known being Astral Oil, a kerosene lamp oil that was purer than any other on the market. Astral Oil was the most popular lamp oil in the country at a time when most homes and businesses were lit by kerosene.

Pratt was self-made in the best sense of the phrase. He came from a Massachusetts family of 10 children, and his father was a carpenter. As a young man he worked for a Boston company that specialized in the refining and sale of whale oil, which was used in lamps and lighting. Around 1850 or 1851 he moved to New York and began working for a similar company. He began to realize that whale oil was a finite product; whales had already been slaughtered by the thousands and were on a path to extinction. A new fuel was needed, as word came out that oil had been discovered in Venago county in Western Pennsylvania. He went to check it out, realized petroleum’s potential, and was drawn into the oil business.

The Charles Pratt Company’s main competition was John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. The two had many disputes, primarily over Rockefeller’s lock on most of the railroads bringing the crude oil to New York. After several rancorous years, the men decided that a merger was better for all parties than continued competition. In 1874, papers were signed as Astral/Pratt Oil joined the Standard Oil family. Both Pratt and Rogers made out very well, and with the signing of the contract, Charles Pratt rose to the top of the wealth list in Brooklyn.

When Charles Pratt became Brooklyn’s richest man in 1874, he already had ideas for what he was going to do with his money. One of his first expenditures was a fine new mansion on Clinton Avenue on “The Hill,” the 19th century name for what is today’s Clinton Hill and Fort Greene. Another was most of the funding for two Baptist churches in the neighborhood. The first was Washington Avenue Baptist Church in 1860, followed by Emmanuel Baptist Church on Lafayette Avenue. It began as a small chapel on St. James Place in 1882, built in anticipation of a much larger structure. This building is now part of today’s Emmanuel. All three buildings were designed by Brooklyn architect Ebenezer Roberts.

Clinton and Washington avenues were becoming popular streets for suburban development beginning in the 1850s. Both were lined with large villas with ample grounds around them, built as breezy suburban respites for the factory and mercantile owners whose businesses were down the hill along Wallabout Bay. Smaller wood-framed row houses and detached middle-class housing were also springing up on surrounding streets in this growing neighborhood. Churches and small businesses soon followed, as did rows of masonry attached houses.

Pratt realized that the working world was changing rapidly. Every day it seemed as if new inventions, new technological advances, and new ways of manufacturing were being created. Brooklyn was rapidly growing as a major city as undeveloped blocks and new neighborhoods filled up with housing and commercial buildings. And the building trades needed skilled people who were educated in the new methods and materials of construction.

Beginning in 1884, Pratt started purchasing large parcels of land in his neighborhood. In 1886 he founded and built the Pratt Institute only a few blocks from his home. The first buildings were completed and the institution opened in 1887. The college was established to educate and train working class people. It was one of the first colleges in the country that was open to all regardless of race, gender, or class. Courses were offered in fine arts, architecture, engineering, mechanics, dressmaking, and furniture making.

Because Pratt considered drawing to be a universal language, all classes had a strong emphasis on drawing. Even though he never went to college himself, Pratt also wanted his graduates to have a well-rounded education, so classes in history, literature, mathematics, and physics were also taught. He felt such studies would help students understand the world they were living in and were creating.

The school was a rousing success. The first class had 12 students. Six months later, there were nearly 600, and by the school’s first anniversary, there were nearly 4,000 students. During the college’s first year anniversary, Pratt told the classes, “Be true to your work and your work will be true to you.” In other words, work hard here and then go out there and make something of yourself with the skills you were taught. This lofty goal was followed by the generations that came after, to this day.

The Morris Building Company

Pratt Institute was adding more and more buildings to its campus. The area around the college going north towards the East River was also developing as an industrial area. Pratt money was going into a lot of building projects. What better way to both keep costs in house and perhaps give engineering and architecture students some on-hand practical experience than to establish your own building company? The origin of the Morris Building Company name remains unknown, but it may have been an homage to William Morris, the much admired British artist and style-maker who was changing architecture and decorative style in both England and America.

Perhaps the firm was inspired by Morris’ famous quote, “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” Certainly the future designs of the company would prove to be artistic, practical, and well built.

Papers submitted in Albany certify that the Morris Building Company was incorporated on May 27, 1884, the same year Pratt began buying Clinton Hill property for his school. The corporation opened with capital stock of $100,000. The trustees for the first year were William Phelps, Frank H. Kimball, Elfred Ely, George W. Penwarden, and Norman P. Heffley.

There were no Pratt family members on this board, but Francis (Frank) Kimball would become the architect of the main body of Emmanuel Baptist Church in 1887. Later, in 1891, he also designed the Montauk Club in Park Slope. Norman Heffley worked with Charles Pratt as his secretary for Charles Pratt & Co., and soon became the secretary of the executive committee of Standard Oil. Heffley accompanied Pratt on a European trip, and on his return in 1889 resigned from Standard Oil and joined Pratt Institute as a professor in the school’s Department of Commerce. His particular expertise was in shorthand systems and practices.

It’s important to note that the firm was not just a construction company. Most of their listings throughout the years show that they were a developer as well. They bought property and developed it, often keeping whatever the project was for rental purposes, as well as selling outright. As the company entered the 20th century, most of their work was in development, with outside builders.

The Morris Building Company was in place as buildings began populating the new Pratt Institute campus. Brooklyn’s Department of Building notices in the newspapers and in the Real Estate Record and Building Guide, a trade periodical, show that the Morris Building Company was the builder of most of the Pratt campus buildings, both when Charles Pratt was alive and on into the 20th century. The company also was responsible for many of the factory buildings that surrounded or were part of the campus, including buildings on Dekalb Avenue, Willoughby, Ryerson, and more.

As a frugal investor, Pratt figured that should Pratt Institute not work out as planned, the factory-style buildings on campus could be easily converted to industrial use. And if the campus continued to grow, then the buildings off campus that were being used as factories could be incorporated into the campus. This was a successful tactic that added several buildings to Pratt over the years. Most of the buildings that were not incorporated have since been torn down, both for Pratt expansion and other 20th century urban renewal housing.

Buildings need architects, and the Morris Building Company was no different. Various people designed buildings throughout the company’s existence, but the firms of Lamb & Rich and William B. Tubby produced much of the company’s best work. Both began their collaboration with Morris through their Charles Pratt connections.

Hugh Lamb and Charles Alonzo Rich were Manhattan-based architects known for their fine design work. Lamb generally handled the business end of the business, while Rich was the designer. Their first building for the Morris Building Company was an apartment building called the Inwood, located at 246 and 248 Vanderbilt Avenue and built in 1885. The building was touted as a superior design, with all the modern amenities and features. Apartments were already rented before the building was complete. The Inwood is still there, amazingly enough.

The firm went on to design the Astral Apartments on Franklin Street in Greenpoint for Charles Pratt. The large building was built in 1886 as apartments for workers at the Astral Oil Works. Pratt was quite progressive in his desire to provide decent housing for his employees. Most industrialists of the day, especially those in urban areas, didn’t give it a thought.

Lamb & Rich designed a beautiful Queen Anne-style building with an interior courtyard, lots of natural light and ventilation, and interior amenities (bathrooms!) that most tenement housing did not have. The building bristled with exterior terra-cotta ornamentation and remains beautiful to this day. Pratt also established one of the first kindergartens in the building for his employees’ children along with the building’s own library. The Astral was one of the earlier projects built by the Morris Building Company.

In planning his educational campus, Pratt chose Lamb & Rich to design the Main Building, the first building at Pratt Institute, which opened in 1887. It’s a large, impressive six-story Romanesque Revival-style building around which the rest of the campus was built. In 1889, architect William B. Tubby designed a new entrance for the building. Keeping with Lamb & Rich’s Romanesque style, Tubby designed a double arched front entry supported by three sets of two columns, which constitute a porch. There are also arched openings on the fenced-in side elevations. Above the entry on all three sides is a band of decorative terra-cotta ornamentation. This was just the beginning of Tubby’s Pratt campus involvement and another Morris Building Company construction project.

William Tubby was already well established with the Pratt family. He was working in Ebenezer Roberts’ office and began designing projects for the family after opening his own office in 1883. He became the go-to architect for the Morris Building Company and designed some of their best buildings.

The company began building speculative housing in the Clinton Hill and neighboring Bedford. Pratt saw building affordable housing for working and middle class people as good business as well as a benefit to society. Tubby designed most of the groups of houses. Most lots in the area are 18 to 20 feet wide. All the Morris Building Company attached homes designed by Tubby are much narrower, some only 13 feet wide. This enabled the firm to squeeze another house on lots that might have originally been wider. That often results in adjoining houses with the house number next to the same number with an “A,” such as Nos. 286 and 286A.

The row at 286 to 290 Vanderbilt Avenue is the first Tubby group for the Morris Building Company, built in 1889. These four houses were designed in the Queen Anne style of architecture, and are the narrowest of his houses, averaging 12.7 and 13.5 feet wide. Tubby made it work, with a center stair that allows the main rooms to be the full width of the house.

All of Morris Building Company’s housing is first quality. The Pratts were not interested in quicky cheap buildings using inferior materials. They intended them to last and provide income to the company if retained. Tubby would go on to design several more groups over the next few years for the company, including 129 to 135 Cambridge Place (built 1894) and 384 to 396 Lafayette Avenue in 1892. Across the street but now long gone was a similar group of 10 houses.

His houses at 179 to 183 St. James Place, also built in 1892, are the best designed of all, a wonderful group of three Queen Anne/Flemish Revival homes. No. 181, the center house, is the most ornate with stepped gables. All three houses are quite eclectic with all sorts of decorative details. Across the street from these houses are 206 to 210 St. James, another group built for the Morris Company in 1890, designed by Benjamin Wright.

Charles Pratt had six sons. The four oldest were gifted Brooklyn mansions when they married. Tubby designed eldest son Charles M. Pratt’s mansion across the street from his father’s in 1890. The mansion at 241 Clinton Avenue is a masterpiece of Romanesque Revival architecture, regarded as the finest of that style in New York City. The Pratts also commissioned Tubby to design a large carriage house for the family at 261 Vanderbilt Avenue, behind the senior Pratt’s house. It was being constructed at the same time as the mansion.

A year before the Charles M. Pratt mansion was being built, Tubby also designed a solid stone Romanesque Revival mansion at 405 Clinton Avenue for Charles Schieren, a wealthy industrialist who was elected one of the last mayors of an independent Brooklyn. The Morris Building Company was responsible for all three buildings.

Over the next 10 years, before and after Charles Pratt’s death in 1891, the Morris Building Company expanded by going into land purchases and development in many parts of Brooklyn, and occasionally in Manhattan and elsewhere. Their head office was at 26 Broadway, in lower Manhattan. They developed row houses and semi-detached and flats buildings throughout Bedford and Clinton Hill, some by Tubby, as well as other architects. Their factory buildings were throughout the Wallabout area and around Pratt Institute. One of their largest factories, designed by Tubby, was the large factory and subsequent additions built for the Chelsea Fiber Mills at 1155 Manhattan Avenue. As it happens, the mill’s treasurer in 1900 was George Pratt, Charles’ son.

A Brooklyn Enclave Called Kensington Park

Although it wasn’t announced or advertised as such, it didn’t take long for those interested to know that the Morris Building Company, Pratt Institute, and the Pratt family were connected. The annual stock report, posted in the local papers in 1885 was a definite clue. It stated the company’s stock worth and listed the company’s board as William Phelps, president, and Charles M. Pratt and Alfred Ely as board members.

The company’s offices moved to 207 Ryerson Street, which is the address of the Pratt Main Hall building. The Pratt-established bank, called the Thrift, posted an ad in the Brooklyn Eagle in 1894 announcing home loans, arranged through the Morris Building Company. The Thrift was also housed in a Pratt Institute building.

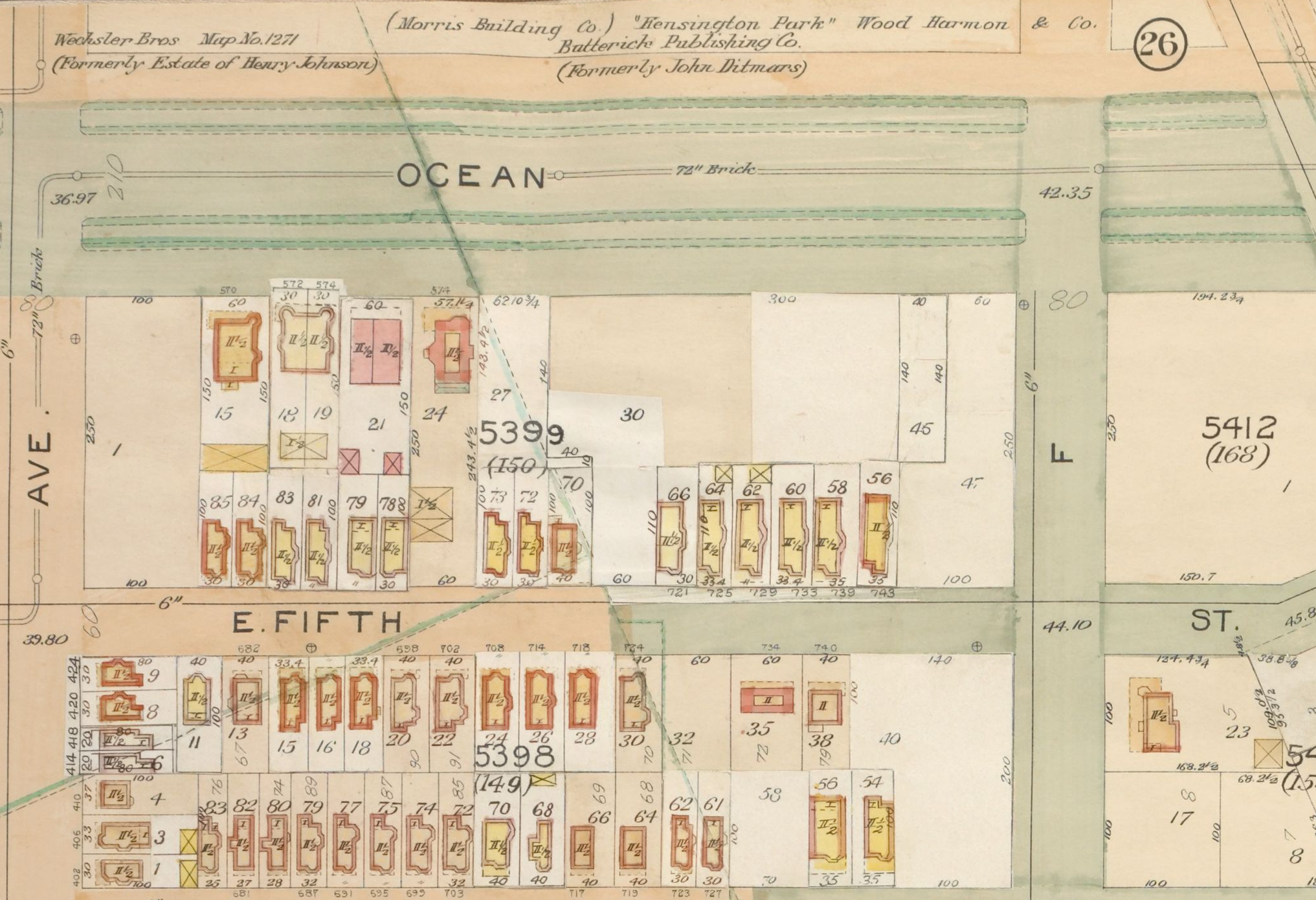

In April 1899, the Morris Building Company purchased 60 acres of land in the Kensington section of Brooklyn, then an undeveloped part of the 29th Ward. The land was purchased from the Butterick Publishing Company, which was the country’s largest manufacturer of sewing patterns. The firm paid $210,000 for it, at $3,500 an acre. The papers noted that Charles M. Pratt was the president and that this purchase was not connected to the company’s funds set aside for the maintenance of Pratt Institute.

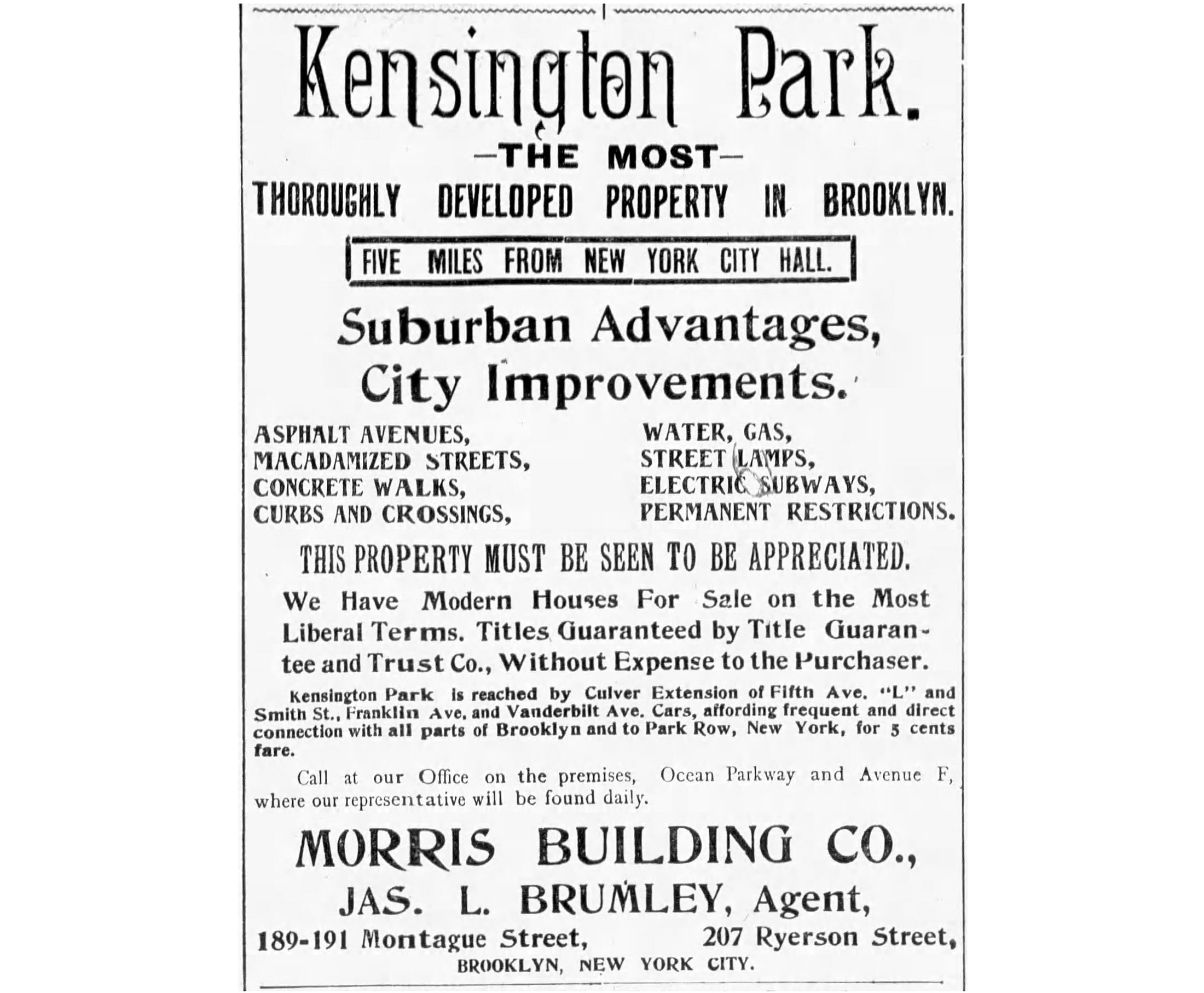

Work on the land began soon after, now called Kensington Park. Franklin Avenue, which runs through the property, was enlarged and paved, with landscaping throughout. Sewers, water mains, and gas and electric lines were laid out along the lots, and the company planned to build a variety of houses on various sized lots, all “first class residences of approved design,” as their advertising stated.

The Morris Building Company would construct some of the houses and would also sell lots to approved developers to develop. Elevated train lines and trolley services were expanding in this part of Brooklyn, and Kensington Park would have its own stop. Public transportation already went past on its way to Coney Island. The company estimated it would take a Kensington commuter 25 minutes to reach the Brooklyn Bridge, where a different train would carry them to Manhattan. It was “only five miles from NYC City Hall!”

The surrounding neighborhoods of Borough Park, Dyker Heights, and Bensonhurst were rapidly developing as well, which meant even more services coming to Kensington Park. As the company completed the first houses, ads in the papers grew larger and larger, all touting the neighborhood’s suburban/urban appeal, with new schools coming and more. The company offered loans at low rates and other perks to attract homeowners and builders.

Kensington Park is no longer a recognized area, and very few houses initially built by the Morris Company survive. Most of the neighborhood is now a combination of later mid-century tract housing and apartment buildings. It is now considered a part of the large Borough Park neighborhood.

In 1915, the Morris Building Company constructed a new post office for the Pratt neighborhood. It once stood at Willoughby Avenue and Steuben Street. The post office was a state of the art building and included shower facilities for the 50 mail carriers and workers assigned to it as well as the newest equipment. Postal officials called it the finest station in the group of eight stations slated to be constructed across the city.

The Morris Building Company continued to build, taking on projects outside of the city. Charles Pratt bought a large amount of acreage in Glen Cove on Long Island to build a summer home for himself and enough land for his children to build their own homes within the family compound. William Tubby, who was now a friend of the family, as well as their favorite architect, was brought in to design a large stable and clock tower complex that would be the heart of the enclave.

When Charles Pratt died in 1891, the family commissioned Tubby to design a large mausoleum for the patriarch and subsequent family members. He designed a simple but beautiful Romanesque building which today holds many of the Pratt family descendants. All this construction, as well as that of the children’s own homes, was, of course, carried out by the Morris Building Company.

In 1923 the company, now run by the Pratt family, donated 30 acres of land in Glen Cove to be used by the town as a park. The undeveloped land included two lakes, valuable uplands, and land near the main roads. The Morris Building Company stockholders were the official owners of the land, which was worth $50,000. The president of the company, Herbert Pratt, and his brothers passed the title to city officials as a gift.

By 1930, Frederick B. Pratt was the president of Pratt Institute, the Chelsea Fiber Mills, and the Morris Building Company. He was also the vice-president of the Thrift Association, and the director of a bank in Portland, Oregon. He was perhaps the family member most associated with his father’s endeavors. Two of his brothers were executives of Standard Oil and not as involved, although they all were active in the affairs of the college. Charles M. Frederick, another Charles, and Richardson Pratt Jr. (Charles M.’s grandson) were all president of Pratt Institute.

Frederick died in 1945. That November, it was announced that the Morris Building Company filed for dissolution. The firm was responsible for the development and construction of hundreds of buildings of various uses and lasted 61 years. Their work can still be seen all around Brooklyn and beyond. Charles Pratt would have been proud.

Related Stories

- Suzanne Spellen’s Tales of Brooklyn History and Architecture in 2024

- Greenpoint’s Astral Apartments: A Building Ahead of Its Time

- Newly Digitized Negatives Give a Glimpse of Mid-Century Life Around Pratt Institute

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment