J. S. Kennedy and the “Modernization” of Brooklyn Heights

Brooklyn Height’s status as the “first suburb” is both a blessing to the neighborhood, and a curse.

Exterior of 150 Clinton Street, as per J. Sarsfield Kennedy, 1921. Image via Brooklyn Eagle

Brooklyn Height’s status as the “first suburb” is both a blessing to the neighborhood, and a curse. The blessings are rather obvious: proximity to Manhattan, lots of public transportation, and of course, great architecture, with beautiful homes and apartments. The curse is its proximity to Manhattan; ease of public transportation, and, of course, great architecture. Popularity was going to kill the Heights. Its homes and streetscapes have been re-invented so many times that many of its grand and humble homes have been changed, revamped, and changed yet again, sometimes not for the better.

When the city passed the landmarks law in 1965, Brooklyn Heights became the first landmarked district. And thank goodness, because at the time, this neighborhood was in the midst of two upheavals; with Robert Moses trying to reshape the Heights by tearing it down, and individual landlords seeking to turn what would be left into blocks of small apartment buildings, with new entrances created from removing the stoops and placing entrances on the ground floor.

But neither of these forces were the first to try to change the streetscapes. Back in the early 1920s, another man with big plans began to buy up houses in the Heights. His goal was not to tear them down, but to make those old row houses modern. The Victorian Age would meet the Flapper Age, and James Sarsfield Kennedy was the man to do the job right.

J. Sarsfield Kennedy was a brilliant architect. He’s responsible for some of this city’s most creative residential and civic buildings, all built in the first half of the 20th century. His most famous building is his “Gingerbread House,” the eclectic Arts and Crafts style cottage he designed in 1916 for Howard and Jesse Jones, in Bay Ridge. He designed houses in Victorian Flatbush, and Laurelton, Queens; all quite different from each other, and all quite interesting, and he was the architect of the late lamented Boat House for the Crescent Athletic Club, also in Bay Ridge. Anyone who frequents Prospect Park should be familiar with his Picnic House, built in 1927, as well as his comfort station for the Ocean Avenue entrance to the park.

Kennedy was a diminutive man, less than five foot five, a Canadian from Barrie, Ontario, sixty miles north of Toronto. He had building in his blood; his father and grandfather were both architects, and had built many of the churches that dot Ontario’s landscape. He also had wolverine blood, apparently, taking after the scrappy little animal that could terrorize even the fiercest opponents. He learned both hockey and lacrosse as a boy in Canada, and over the course of his youth, had his nose broken five times, and had over 350 stitches (his count) over his body and hands. He weighed only 109 pounds, and was covered in scars, and even as he established his architectural practice, he was playing hockey and lacrosse for the Crescent Athletic Club of Brooklyn Heights.

They loved him, he was fearless, and he won games. Everyone called him by his nickname, Sars, and he was usually the hero of the day. He once went head to head with the famous Native American athlete Jim Thorpe, in a lacrosse game at the Crescent’s field in Bay Ridge. Thorpe, who was twice Sars’ height and weight, was worried that he might injure the much smaller player. Sars wasn’t worried, and according to legend, ran circles around Thorpe, even to the point of injuring him enough to require stitches. Of course, they became great friends.

He was a legend in both hockey and lacrosse, and in 1960, long after his death, was inducted into the Lacrosse Hall of Fame. He would probably have his place in search engines for his sporting activity alone, but he was also quite a successful architect and developer. He always lived in Brooklyn Heights, probably to be near the Crescent, and became very active in Brooklyn development. He and his partners formed the Jackbert Realty Company, and began buying up houses in the Heights.

World War I had ended, and the troops were coming back home to a Brooklyn that didn’t have enough apartments for all of the people who wanted to settle down in its neighborhoods. The children and grandchildren of immigrants could now afford more, and were looking to the “outer boroughs” for a more gracious living than their parents ever had.

The 1920s were the beginning of working and middle-class Brooklyn’s apartment boom. All across the borough, apartment buildings were going up, especially in neighborhoods like Flatbush, Crown Heights, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights and Park Slope; sometimes replacing large mansions that were no longer desirable to the wealthy, who were decamping to the new suburbs or Manhattan high rises. Many of these neighborhoods had undeveloped land that was perfect for large six story apartment buildings, but in many neighborhoods, like Brooklyn Heights, that kind of building was impossible.

Brooklyn Heights was full of mid to late 19th century row houses, a few remaining private mansions, and some large residential hotels and apartment buildings. Sars and his partners decided to renovate, rather than tear down, and thus began their mission to modernize the old buildings of Brooklyn Heights. They were not alone; other developers were also eyeing the Heights. Some were tearing down row houses and mansions to build apartment buildings; others were also changing the face of the Heights, one house at a time. Some were hacks; others were fellow prestigious architects, like the firm of Slee & Bryson, who were among the best of the Colonial Revival-style architects, with projects throughout Brooklyn.

The local papers eagerly embraced this period of renovation, and penned articles that read like a horror story to most present-day preservationists. In May of 1919, Sars told the Brooklyn Eagle, “The large number of alterations of old-time palatial homes on the Heights to apartments is due to war conditions. This after-effect of the war will be felt in Brooklyn for five years to come.” He spoke about how these large houses were becoming a financial and physical burden to elderly parents, and how the younger generations were going out on their own, and wanted their own apartments. “I saw how things were shaping up many months ago, and associating with me a number of capitalists, bought a number of the old houses on the Heights and have made a very profitable investment.”

The article was accompanied by a photograph of 143 Montague Street before and after his alterations, which, on the façade, consisted of removing the stoop and the balconies, and changing the entrance to a street level Colonial Revival doorway. He also replaced all of the windows, and put muntins on the arched ground floor window, giving it a Colonial look as well. The exterior was finished off with a simple wrought iron fence. Most of the alterations actually took place on the inside of the building, where the single family home was divided up into apartments. A look at the building today shows that Kennedy’s exterior alterations were nothing compared to what was done even later, as Montague street commercialized, and the two bottom floors were turned to retail business spaces.

A month later, the paper announced that Kennedy had purchased the Dunning residence, at 27 Monroe Place. It had always been in the Dunning family, and was being sold by the estate. The house had 24 rooms, and was going to be turned into “bachelor apartments” by Kennedy. Once again, he removed the stoop, resized the parlor door into a window, and created a ground floor entrance. He also put in a separate service entrance. He probably also reconfigured the attic windows so that this former servant’s quarters could be renovated into a modern apartment. His new entrance was a subtle arched entryway, in stucco.

Two years later, Sars was in full swing with his projects, still getting favorable press. He got two articles in February of 1921. The first was about his alterations to a row of brick houses on Orange Street, at the corner of Hicks. The Eagle calls Kennedy an “architect-magician” for modernizing the old houses for the present. The “large rambling rooms” had been transformed into “suites of comfortable and cozy dimensions, the heavy plasterwork replaced by artistic paneling and decorations.” The basements had been reconfigured into complete apartments and the entrance on the ground floor “redeemed from its brownstone ugliness.” New Colonial balconies replaced the original stoops, making the houses “picturesque again. They are no longer old fashioned and dejected looking, but are an attractive feature of the neighborhood in their new attire of respectability.”

The “protruding cornice and coping” had been removed, giving the houses a “more dignified façade effect with a treatment of stucco.” Inside, “the old time drawing room is now a living room, in which the heavy woodwork, chandeliers and plaster have been substituted by artistic paneling and modern lighting effects.” I can’t go on. Today, the row retains some of Kennedy’s exterior changes, but again, later changes were made to his changes, and those are not as good.

The last article I was able to unearth, also from 1921, showed his most ambitious row house project, one that has not survived the years any better than the facades he messed with in the first place. Again, the Eagle would opine, “Dismal old brownstone houses in rows have been rejuvenated and the remodeling of one house in the group brightens up the entire block and relives the monotony of architectural sameness.” They go on to say, “The pompous fronts of some of the brownstone dwellings, popular a generation ago, have been toned down, but in the general treatment, where possible, the aristocratic atmosphere, which is so much a part of the history of the Heights, is retained.”

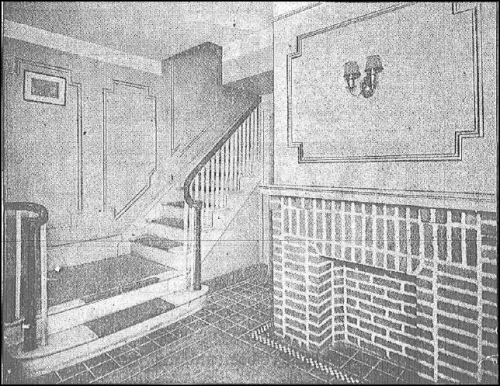

Sars and his team took 150 Clinton Street, and turned this large Greek Revival house into an Italian Renaissance fronted apartment building. He added a new top floor, removed the stoop, stairs and original front door, as well as the cornice. In its place, he installed a step-down front door in the center of the building, with an ornamental iron gate, and placed decorative niches on the sides, flanking a large bay window with diamond paned leaded and stained glass, reminiscent of a Venetian palazzo. The paper printed a photo of this new entrance.

They also showed the hallway, which had been transformed in the very popular Colonial Revival style to resemble a hallway from the 1700s. The rest of the building had been transformed from a single family home into small apartments. It’s rather interesting that this “modernizing” would involve invoking an even older by-gone era, and was in effect, not modernizing, but regressing back even farther back in time, to the 18th century. And the Italian Renaissance? Well, it made for a very interesting façade, but unfortunately, this “modernization” was itself “modernized” by less talented architects, who later stripped all of Kennedy’s rather delightful details (I would have loved to have seen them elsewhere, in his own building, not a retrofit) and gave us plain.

J. Sarsfield Kennedy had other projects here in the Heights. It would be an interesting project to see what other modernizations he effected, and how they compare with other efforts to change Brooklyn Heights into a Colonial Revival town. Although he removed cornices, stoops and railings, his work was not the slash and destroy work of some of the others who stripped every detail from every building they encountered. He was smart and canny enough to see that apartments were the wave of the future, and that room in New York City’s “first suburb” would be a precious commodity. In many ways, the transformations helped keep the buildings from being torn down altogether, so his legacy here in the Heights can be seen as a mixed blessing. And the scrappy little guy was really one hell of a good hockey player, too.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment