Industry City's Rise, Fall and Rebirth, From Wartime Manufacturing to Artisanal Mecca

Read Part 1 of this story here. The huge gray cement factory buildings that span Sunset Park’s shoreline between 30th and 37th streets are the remaining structures of Brooklyn’s largest industrial park, Bush Terminal. The complex was the brainchild of Irving T. Bush, the son of an oilman-turned-yachtsman. Today, these buildings are known as Industry…

Read Part 1 of this story here.

The huge gray cement factory buildings that span Sunset Park’s shoreline between 30th and 37th streets are the remaining structures of Brooklyn’s largest industrial park, Bush Terminal.

The complex was the brainchild of Irving T. Bush, the son of an oilman-turned-yachtsman. Today, these buildings are known as Industry City, an evolving complex made up of workspaces for Brooklyn’s creative economy, as well as future dining, entertainment and shopping destinations.

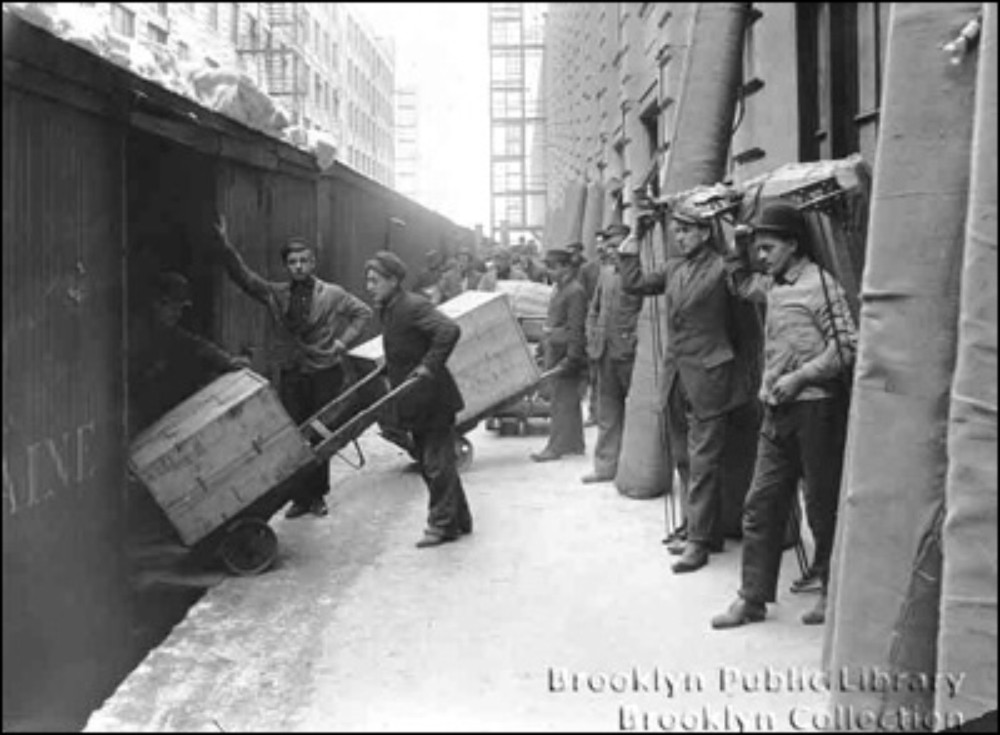

At its height, during World War II, Bush Terminal was the largest multi-tenant complex in the United States, employing more than 25,000 people. It was its own city, self-contained with its own power plants, private railroad and streets, police and fire departments.

The terminal started out with the familiar late-19th-century-style brick warehouses and storage facilities. But beginning in 1906, Bush retained William Higginson, an English-born architect who specialized in factories.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Higginson was introduced to the wonders of reinforced concrete construction through Robert Gair and the Turner Construction Company, the history of which we shared earlier this year. He never looked back.

Higginson’s first concrete factories were the Gair buildings in Dumbo, the most familiar being 1 Main Street, with its iconic clock tower. Many more followed.

Having no lack of space or financing, Irving T. Bush had Higginson design rows of block-long six-story factory buildings for Bush Terminal between 1906 and 1928.

Today, these buildings define the complex, but they were not the entirety of it. There were also many smaller brick warehouses and other buildings behind them, as well as the piers and the rail system.

During World War I, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt appropriated the piers and warehouses, and kicked everyone out of four of the new factories. They were all turned over to military use.

Bush countered by developing the largest reinforced concrete facility the Army could ever want — the U.S. Army Military Ocean Terminal. He employed architect Cass Gilbert and Turner Construction to design and build what is now considered an industrial masterpiece, built in only a year.

At the war’s end, Bush got his terminal back.

World War II

The Depression years saw a slowdown, but by World War II the Terminal was at full strength again, due to war-related manufacturing. Again, the government came in and took what it needed.

F.D.R. came back to the Terminal to tour the wartime operations, this time as President. Women had become important workers at Bush, doing everything from “Rosie the Riveter” jobs, to general factory work to employment as “longshore girls.”

During the war, the train cars that shipped freight were often repurposed for a grim task. Ships coming back from Europe carried the war’s dead. Caskets were loaded from ships onto the railroad cars called “burial cars,” barged to the mainland or Manhattan, and sent on their way across the country.

In 1939, Robert Moses had started the separation of Bush Terminal from the rest of Sunset Park by building the BQE on the pillars of the old 3rd Avenue El.

He destroyed hundreds of buildings for the highway and its on and off ramps, and more for the highway’s widening in 1955.

The Post-War Years

In 1948, after seeing his massive enterprise thrive through two World Wars, Irving T. Bush died at the age of 79. He wouldn’t have been pleased with the future, anyway.

During the 1950s, the terminal continued to thrive, as companies such as Topps Candy Company became tenants. Topps famous baseball cards were printed here, in addition to the manufacture and packaging of their gum. Topps left in 1965.

The rail and shipping system that had been the unique drawing power of the terminal was becoming obsolete. By the 1960s, New Jersey’s container ports were taking away business from all of Brooklyn’s ports, and trucks were the preferred transportation, not trains.

In 1963, Harry Helmsley and his co-investors bought Bush Terminal. The factory buildings became the most concentrated garment-related center outside of Manhattan’s Garment District. In spite of that, by the late 1990s, many of the buildings were only partially occupied.

In the mid 1980s, the Terminal was rechristened “Industry City.” Plans to bring back manufacturing were drawn up, and the complex was marketed toward artists, artisans and small manufacturers.

An art gallery was established — the Marion Spore Gallery, at 55 33rd Street, named after Irving T. Bush’s third wife, a controversial and well-known artist in her own right. Unfortunately, that gallery was before its time, and has since closed.

The arrival of Costco and other retailers in the area brought people to the Bush Terminal area for the first time in years, and huge companies like Time Inc. and Amazon have taken up office and warehouse space, respectively.

The potential of these buildings was obvious. But so was the downside — the sheer amount of square footage, the work needed to upgrade and, most importantly, the isolated location, quite far south in Brooklyn off the D, N and R trains at 36th Street.

Today, new plans are underway for this historic site. Local food purveyors and artists are continuing to pursue their work there, and the Brooklyn Flea and Smorgasburg are bringing in foot traffic on weekends throughout the winter.

And there’s a $1 billion redevelopment plan by the complex’s owners — Jamestown Properties, Belvedere Capital and Angelo Gordon, along with Cammeby’s International and FBE Limited — in the works.

Over the next dozen years, this massive amount of capital will be used to renovate, repurpose and revitalize the complex, eventually bringing 20,000 jobs to the vast industrial hub.

Industry City won’t return to being its own city as it was during World War II — but it’s becoming a vital part of Brooklyn’s fabric, well on its way to being great again.

Related Stories

How Bananas Built Industry City — the Story of Sunset Park’s Bush Terminal

How Reinforced Concrete and Turner Construction Changed Brooklyn and the World

Tech Giant Amazon Expands to Sunset Park, Near Industry City

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment