A Lost Daughter and the Women of a Brooklyn Heights Greek Revival Showpiece

Behind every architecturally entrancing building in Brooklyn, there are equally compelling tales of the lives of those who once called it home.

Photo by Susan De Vries

Behind every architecturally entrancing building in Brooklyn, there are equally compelling tales of the lives of those who once called it home. Those stories often take more than a bit of digging to unearth, particularly when trying to give names to the women of a household, who were so frequently left out of the narrative.

At 145 Columbia Heights, a recent makeover of the house for the current Brooklyn Heights Designer Showhouse provided an opportunity to roam the interior and do a deeper dive into the lives of those who lived and worked in the house over its 183-year history. An unexpected story popped up of a family member forgotten.

The 19th century

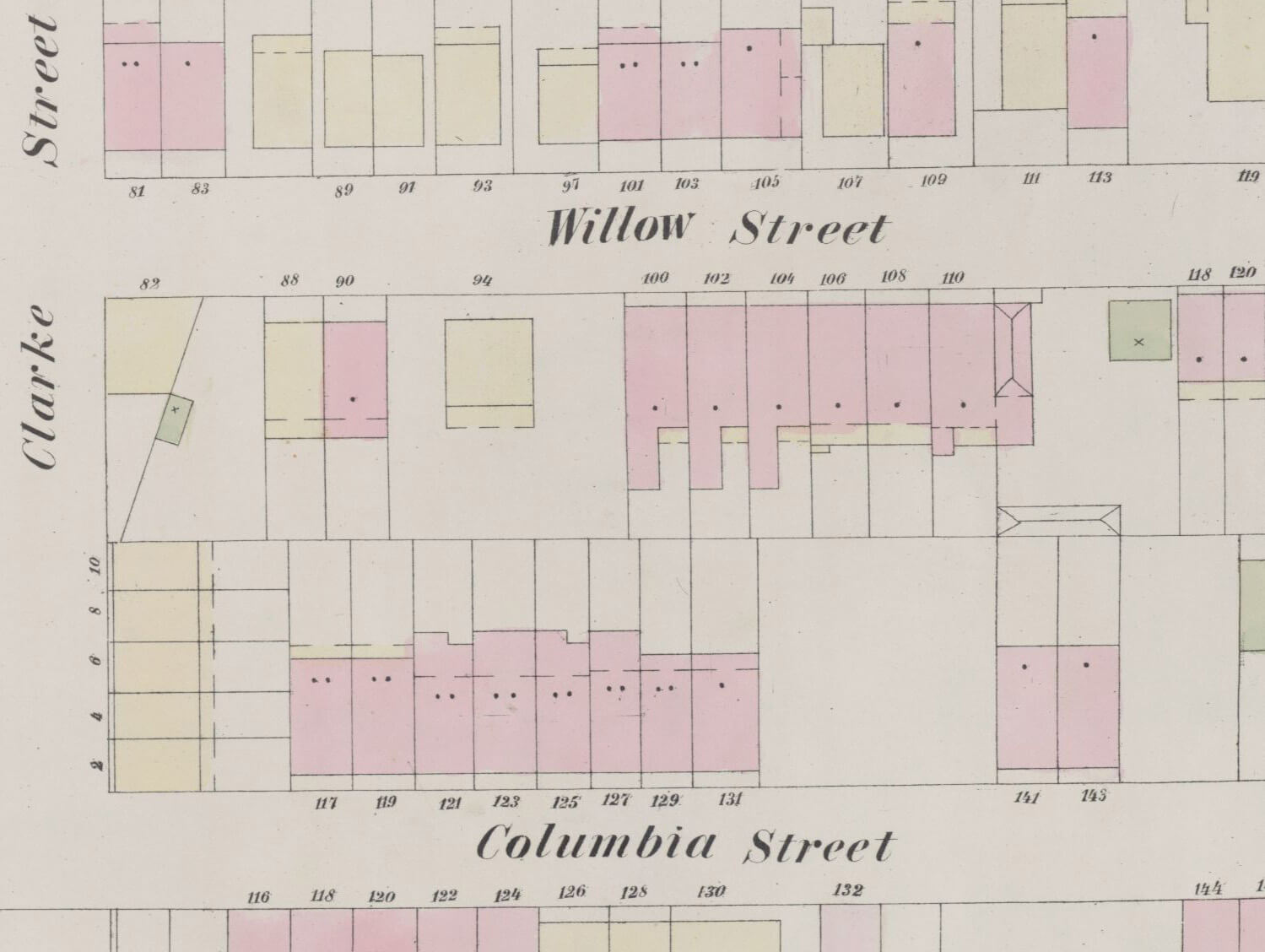

The history of the townhouse begins in 1839 when developer George S. Howland constructed the 26-foot-wide classic Greek Revival house and its neighbor, then known as 117 and 119 Columbia Street. Howland advertised the adjoining three-story houses that year as under construction and available the following April. He promised they were to be “finished in the best manner” with mahogany doors, plate glass, a bathing room, water closet and hot-air furnace. The houses were to include kitchens, tearooms and piazzas and have “an unobstructed view of the city and harbor of New York.”

The exterior of the house that Howland built stands much as it did in when constructed, with one major exception. Still in place is the stone basement, classic columned door surround with Corinthian columns and dentil molding, and the molded lintels across the three-bay-wide facade. It is the house’s simple cornice that is the newer element, and historic images from 1915 show that the house and its neighbor were once topped by a balustrade. Similar balustrades can be seen in the architectural pattern books of the era. The balustrade was gone from both houses by the time the circa 1940 historic tax photo was snapped.

Howland ended up not selling No. 145, maintaining it as a rental property until 1847. Deed research by local historian Jeremy Lechtzin shows that Howland sold the house that year to Tilly Lynde, a lawyer and politician who moved to Brooklyn upon retirement. The following year, Lynde sold the house to his son Martius.

The Lynde Family

The Lynde family moved into No. 145 in 1847 and would retain ownership of the house until 1913. It was a small household in the early years, census records show, with Tilly and Eliza Warner Lynde sharing the house with their lawyer son Martius.

Tilly died in 1857 and Martius remained in the house upon his 1861 marriage to 22-year-old Elizabeth Trowbridge of Detroit. The couple had three children between 1864 and 1868, but tragically Elizabeth and two of the children were dead by 1872. Daughter Libbie died of scarlet fever in 1867 at just six months old, Elizabeth died in 1868 soon after the birth of son Martius Tilly, and Martius Tilly then died before his fourth birthday in 1872.

Martius remarried in 1875 at age 48, bringing Martha Ruggles of Vermont, age 38, to join the Lynde household. That year the New York State census shows the couple in a household that included three immigrant servants: Mary Reid from Ireland and Kate Roberts and Mary Owens from Wales, all in their early twenties.

On his death in 1899, Martius was lauded in a Brooklyn Daily Eagle obit as “a man of prominence” and member of numerous organizations including the Brooklyn Institute, the Brooklyn Library and the Historical Society. Listed as his sole survivor in the obit was his widow Martha Ruggles Lynde. His will gives a sense of what the interior of No. 145 may have looked like during the Lynde years with Martius specifically bequeathing to Martha “sketches, screens and other articles of utility or ornament” produced by the couple and which brought them “a source of common enjoyment.” Also mentioned were family portraits, engravings, mezzotints and books as well as a cabinet of minerals.

His will also yields information on survivors, a very different tale than told in his obituary. Lost from any public acknowledgement at the time of his death was the only surviving child of his first marriage. Emily T. Lynde was born in No. 145 in 1864 and disappeared from mentions of the household after the 1880 census. When her stepmother Martha died in 1910 after moving to the Hotel Margaret, Emily also went unmentioned as a family member.

The reason for her disappearance is clarified in Martius’ will, where he specifies that a portion of his estate go towards the “care, maintenance and support” of daughter Emily and for “her comfort and enjoyment.” In the probate records her address is listed as Bloomingdale Asylum, White Plains.

The Lost Lynde

A hunt for Emily’s story required leafing through thick volumes of patient records preserved in Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Finally, she appeared in 1896 with a full record of admission including an initial assessment and information evidently gleaned from Emily herself.

While her official residence was listed as 145 Columbia Heights, it is clear from the notes that it hadn’t been her home in some time. Her admission to Bloomingdale with a diagnosis of “terminal dementia” was a transfer from a sanitorium in Pleasantville, N.Y., where she was first admitted in 1888. She conveyed to the doctors there that she first felt “unbalanced” in 1886 at age 22 during a church communion service and had a “dread of impending evil.” The intake information notes that the alleged cause was genetic with a “nervous” mother and an “insane” maternal grandmother.

Bloomingdale Asylum moved from what is now the Columbia Campus to White Plains in 1889. Emily was admitted to the new campus and it would be her home from 1896 until the 1930s.

Notes over her years at Bloomingdale record symptoms that without the aid of modern medicine could only be treated with tonics, activities and constant oversight. In addition to documenting her struggles with obsessive behavior and self-harm, patient note entries mention when she was willing to attend trips to the beach or participate in concerts and dances. The only family member mentioned as visiting her was her stepmother, who appears multiple times in the notes. On August 8, 1899 Emily was informed of the death of her father and was “seemingly not affected.”

While Emily was brought back to Brooklyn in 1900 for a court hearing on her mental capacity, it isn’t known whether she ever returned for a visit to 145 Columbia Heights. After leaving Bloomingdale in the 1930s she was moved to St. Vincent’s Retreat for Nervous and Mental Diseases in Harrison, N.Y. She was listed there in the 1940 and 1950 census. She died in 1952 at the age of 87. Her name did then appear in the newspapers as executors worked to settle the Lynde estate.

The 20th Century

By the time of Emily’s death her childhood home had long since passed to another family. The Lynde estate sold the house in 1913 to Christian E. and Elsie Grandeman with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reporting that “important changes” would be made to the house before it was occupied.

Only Mr. Grandeman was mentioned in the press notices about the property, but Lechtzin’s deed research shows that Elsie Grandeman was listed as the official owner of the property when it was purchased and then again when it was sold in 1919.

The new owner was another woman, Mary Murphy, who immigrated from Ireland in 1885. Despite that, census takers assigned the ownership to the men of the household: her husband Timothy A. Murphy, a letter carrier, in 1920 and her brother Jeremiah Donovan in the 1930 census. Mary owned the property until circa 1934, sharing it with her husband, their children, several of her siblings and multiple boarders.

While it housed as many as 12 people during the Murphy years it seems it wasn’t until the late 1930s that the house was first officially converted to a four-family. Bernard and Frances Reswick were the owners at the time, and owned the house until 1954. Census records for 1940 and 1950 indicate the couple, a lawyer and an artist respectively, occupied the parlor level of the house along with live-in maid Edna LeBoo. Born in North Carolina, Edna moved northward at least by 1924 when she was living in Bed Stuy and became a new member of the Bridge Street A.W.M.E. Church.

In 1954 the Reswicks sold the property to Milton and Rosamund Hirschman, and that year a new certificate of occupancy listed it as a five-family residence. Like Frances Reswick, Rosamund was a painter. She studied at the Brooklyn Museum Art School and painted under the name Rozzi.

Cecile F. Blum purchased the house from the couple in 1965 and the house continued as a rental property with Cecile and her first husband, Zevi Blum, an artist, occasionally in residence. In the 1980s Cecile and her second husband, Salvatore Cammarata, opened up the house for benefit concerts and offered the parlor floor of 145 Columbia Heights as the first office for the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLADD). When Cecile died in 1990, Out Magazine paid tribute to her dedication and vision in support of the fledging group.

After it was sold in 1995, the multi-family property was converted to a two-family with alterations, including the conversion of the attic to a modern solarium and the addition of terraces and a roof deck.

The interior certainly reflects centuries of transformation, although there are elements that have survived from the 19th century, including pilasters framing the parlor doors, a curved stair with newel post, moldings and some Greek Revival marble mantels.

There is still a chance to see those details as well as the imaginative interiors created as part of the Brooklyn Heights Designer Showhouse. The showhouse runs through October 30 with proceeds going to support the work of the Brooklyn Heights Association. Tickets can be purchased online.

Below, some photos of the interior of the house before it was transformed for the showhouse.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Brooklyn Heights Designer Showhouse Wows With Architectural Grandeur and Design Imagination

- The Lore of 13 Pineapple Street, One of Brooklyn Heights’ Historic Wood Frame Houses

- Designer Showhouse Brings Color, Bold Design to Historic Brooklyn Heights House (2019)

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment