Welcome, Neighbor! Covenants and Deed Restrictions in Brooklyn

One neighborhood in Brooklyn has an unusual restrictive covenant that has helped it remain economically stable, racially integrated, and fiercely committed to maintaining its special flavor and history.

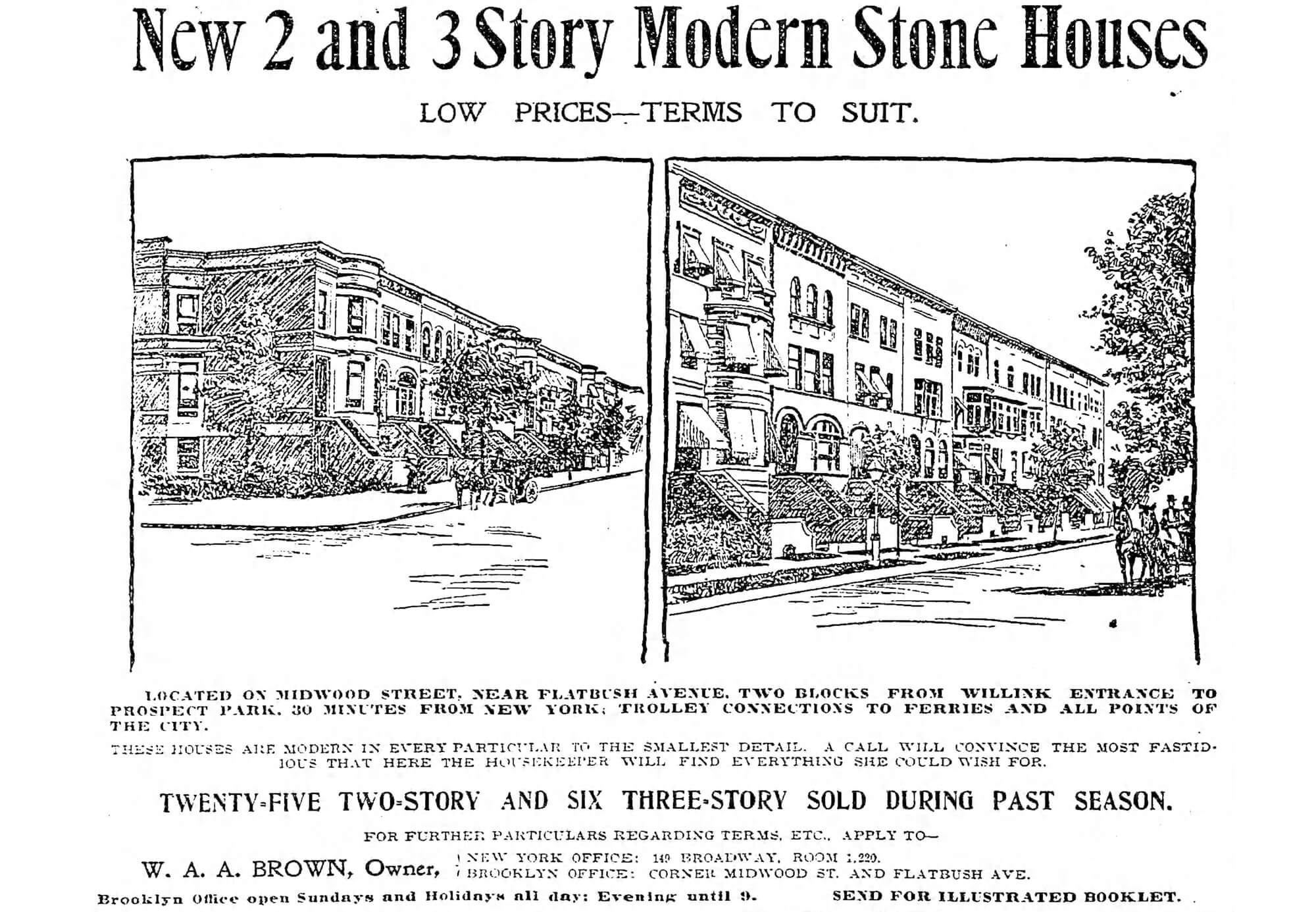

Midwood Street in Lefferts Manor in 1924. Photo via New York Public Library

The dictionary defines a covenant as a “formal, solemn and binding agreement.” A dictionary of legal terms defines a deed restriction as a “private agreement that restricts the use of the real estate in some way and are listed in the deed. Deed restrictions placed within a deed control the use of the property. The restrictions travel with the deed and cannot generally be removed by new owners.” (USLegal.com)

When it comes to the use of property, both terms are often used to describe the same things. Deed restrictions and restrictive covenants have a long history in this country. It seems that people have always looked for a way to control the use of land or property, and/or the people who are allowed to live on it.

There are plenty of deed restrictions still on the books in New York City. But most of them are arrangements made by property holders that prevent the property, or usually the building(s) on that property from being used in a way that is contrary to what the sellers see as a fit use. An example would be a religious entity restricting the sale and development of a house of worship as apartments, or as a retail establishment.

Private owners may also place in writing proscriptions on a subsequent owner from changing a façade, tearing out period detail in an historic house or perhaps an order to maintain a woods or garden. These deed restrictions have to be signed by both parties, and are legally binding, and travel from owner to owner as the property is sold again. It’s hard to make a case that one did not know, or that the death of the original signees makes the restriction null and void.

But those aren’t the restrictions that have an effect on large numbers of people, or specific groups of people. For a long time here in New York, beginning in the late 19th century, deed restrictions sought to create homogenous communities, segregated by written fiat, keeping out unwanted members of certain classes, races, ethnicities and religions. Yet there was one covenant, one deed restriction in Brooklyn that was very different.

Deed Restrictions in 19th century Brooklyn

The towns comprising most of today’s Brownstone Brooklyn developed throughout the 19th century. After the Civil War, neighborhoods like Bedford and Park Slope were seeing large-scale row house development starting to progress, with the bulk taking place in the latter 25 years of the century. There were too many individual property owners working on each block, all eager to make money from the hordes of potential homeowners they envisioned streaming across the new Brooklyn Bridge.

The idea of a restricted community never entered their minds, all that planning would have halted progress. They just built for their targeted markets, knowing that the price of houses would pretty much dictate the kind of people who would probably be buying.

But Flatbush was different. Flatbush was still agrarian long after Brooklyn, Williamsburg, Bushwick and Greenpoint were solidly urban with manufacturing districts. Farmers in Flatbush and further south were still delivering produce and meats to Brooklyn markets up until the 1890s, and from some remote places, into the 20th century.

But it didn’t take an urban planning genius to see that change was coming, especially in those parts of Flatbush closest to Prospect Park, which had opened to the public (quite unfinished) in 1867. The park became a central jumping off point for tourists and day trippers. There were those who wanted to enjoy the amenities of the park, and there were those who boarded trains and omnibuses for the trip to the beaches of Coney Island, with their upscale hotels, ocean breezes and sandy shores.

The park ran south along Flatbush Avenue, met Malbone Street, now Empire Boulevard, and extended along Ocean Avenue to Parkside, and on out to meet Prospect Park Southwest, near the Parade Grounds. These Flatbush lands became very valuable. Many county villas and homesteads, some belonging to some of Brooklyn’s oldest Dutch families were in this vicinity, including homes belonging to the Lefferts and Vanderbilt families. Large and beautiful country mansions lined Flatbush Avenue south of the park.

Many families quickly sold their homes, some of which were turned into hotels and restaurants for the tourist trade. But the smarter landowners saw what the writer of the Rural Gazette saw in Flatbush when he wrote in the magazine in 1872, “The time is at hand when the wealthy citizens of Brooklyn will seek a resting place, and a home near this ‘delectable land,’ where they will be free from the noise and turmoil of the city, yet accessible to it…where there must be, if Flatbush does her duty, the growth of a palatial city, the like of which in wealth, in elegance and refinement, this continent has seldom seen.”

Several developers saw that vision. Perhaps not a palatial city, but certainly palatial suburbs could be created. The best and easiest way to ensure the kind of suburb got built that you wanted your name to be associated with was to start off right and establish restricted covenants. The first one was in a development called Tennis Court.

In 1886, a local developer named Richard Ficken bought some land near the Parade Grounds and established an upscale suburban enclave he called Tennis Court. This was the first of the Flatbush suburban developments, and the first to have deed restrictions. Ficken divided his land into 50 foot wide plots, which he sold for $1,500 each. He laid out pipes for utilities and paved the sidewalks and streets. Tennis Court wasn’t that large, so the houses were pretty close to each other, but each house had to be set back from the street, with a deep front lawn. Every house had to cost at least $6,000 to build, at a time when an average upscale row house cost less than $2,000 to construct.

Ficken built brick gateposts at the entrance to the Court on Ocean Avenue and Tennis Court, and a beautiful garden mall just inside. In 1889, he leased land on the other side of the train tracks from the Court to the Knickerbocker Field Club, which had the Parfitt Brothers design an upscale private tennis clubhouse that opened in 1893. It was one of three local private upscale clubs established for the new landed gentry in Flatbush.

Postcards of Tennis Court show large turn-of-the-20th century suburban houses, similar to those in Prospect Park South and Ditmas Park. However, Tennis Court is now completely gone, replaced in the 1930s by apartment buildings. Now, only the landmarked Knickerbocker Tennis Club building still remains.

Prospect Park South

Tennis Court is important because it was the inspiration for an even bigger and better development – Prospect Park South. Syracuse native Dean Alvord purchased 50 acres of land from the Dutch Reformed Church and the Bergen family in 1899. His goal was to create an upscale suburb in Flatbush that would be the ideal mixture of country and urban life.

The expansion of the Brooklyn, Flatbush & Coney Island Railroad from Lower Manhattan through this area was one of the perks of this new development. What is today’s B and Q subway line had stops on both ends of Prospect Park South. This would be important to the industrialists, movers and shakers that Alvord wanted in his new community.

Alvord advertised that the nearby Flatbush trolley did not pass through any slum neighborhoods as made its way through Brooklyn. He noted in his ads that families in Prospect Park South would not have to be subjected to mixing with “undesirables,” as the trolley was only ridden by “people of intelligence and good breeding.”

He also had a series of deed restrictions that homeowners and builders had to follow. Similar to Tennis Court, the houses had to cost at least $5,000 to build, they had to be set back at least 50 feet, and fencing was prohibited. Hedges were only allowed in the rear to hide any unsightly aspects of the back yards. There were other stipulations as to the placement of the houses, so as to guarantee large lawns, keeping that park-like quality to the neighborhood. The deed restrictions mandated that each homeowner pay into a fund for the upkeep of the common gardens.

Since Alvord controlled who bought into the development, the earliest homeowners were all wealthy Protestants, all of whom had to provide references to Alvord and his sales team before being allowed to buy. In doing so, Alvord fulfilled his promise to buyers that they would only be surrounded in Prospect Park South by people like them. His own home, one of the largest in the neighborhood, became a nexus of the social life in Prospect Park South.

But, like many developers, as soon as they are successful, they want to move on to the next project. In 1905, Alvord sold his remaining lots and moved on to develop Laurelton in Queens, where he instituted many of the same restrictions. As different developers continued to build in Prospect Park South, some of Alvord’s social restrictions were quietly dropped, as wealthy Jewish buyers moved in, along with other people that Alvord would have probably considered “undesirable.”

The Prospect Park South Association, one of Brooklyn’s oldest homeowner’s associations, kept many of the physical restrictions in place for as long as possible, including the mandate for upkeep of the gardens. But as time went by, and economics and demographics changed, smaller houses were built replacing large mansions, and even apartment buildings found their way into the neighborhood, much to the displeasure of many. Today’s Prospect Park South is still special and upscale, but a mixture of incomes, ethnicities and religions.

Prospect Lefferts Garden’s own Lefferts Manor

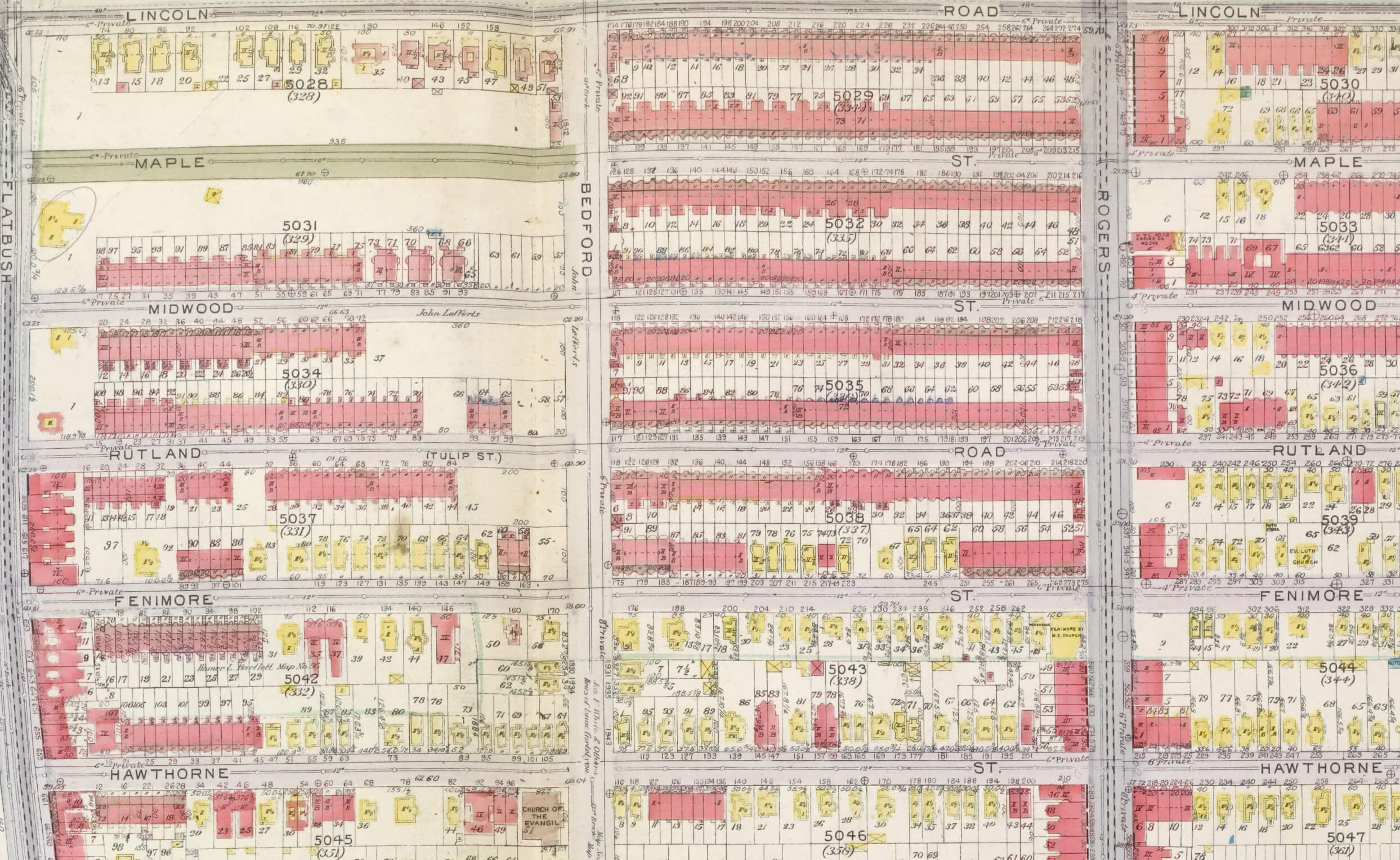

While various other Flatbush developers took hints from Ficken and Alvord in setting up their developments, none were as long-lasting and significant as what was going on in the northernmost part of Flatbush, the neighborhood we know as Prospect Lefferts Gardens.

This was all Lefferts land. As one of the oldest of the Dutch founding families of Brooklyn, the Lefferts family once owned a great deal of northern Flatbush, as well as most of today’s Bedford Stuyvesant, Crown Heights (North and South) and Wingate. Their farmlands were tended by dozens of enslaved people, making them the largest slave owners in New York.

The Lefferts family homestead stood on Flatbush Avenue between Maple and Midwood Streets. The 1780s house stood on the site of the 1680s original, which was burned down during the Revolutionary War. Generations of Lefferts lived there, including James Lefferts, who in 1893 decided to divide part of his vast estate into 600 lots that he would develop as an upper middle class enclave called Lefferts Manor. But like those who would follow him, he had conditions.

Lefferts didn’t want to build an upper class enclave, he was much more interested in building for the growing middle class, although with today’s standards we’d consider most of the early people to be on the upper end of that spectrum, if not downright wealthy. His covenant had stipulations about the kinds of buildings that could be constructed, the distance from the sidewalk, the materials used, and so on.

But what made his covenant so special was the mandate that all of the houses had to be for single families only, now and forever. Lefferts could see that all around him, and in other parts of Brooklyn, developers were building new two-family row houses, and lots of apartment buildings. He could also see houses built as single family dwellings were being used as rooming houses or subdivided into apartments. He did not want this happening in Lefferts Manor. He didn’t want boarders, potential tenant issues and just too many people in the neighborhood ruining its suburban bliss.

Several different developers, architects and builders were engaged to build Lefferts Manor. They were all contracted to build single family houses only. The majority of the earliest houses are classic Brooklyn row houses, most of which were designed by familiar names like Axel Hedman and Benjamin Driesler, who also designed in Park Slope, Prospect Heights, and other nearby neighborhoods.

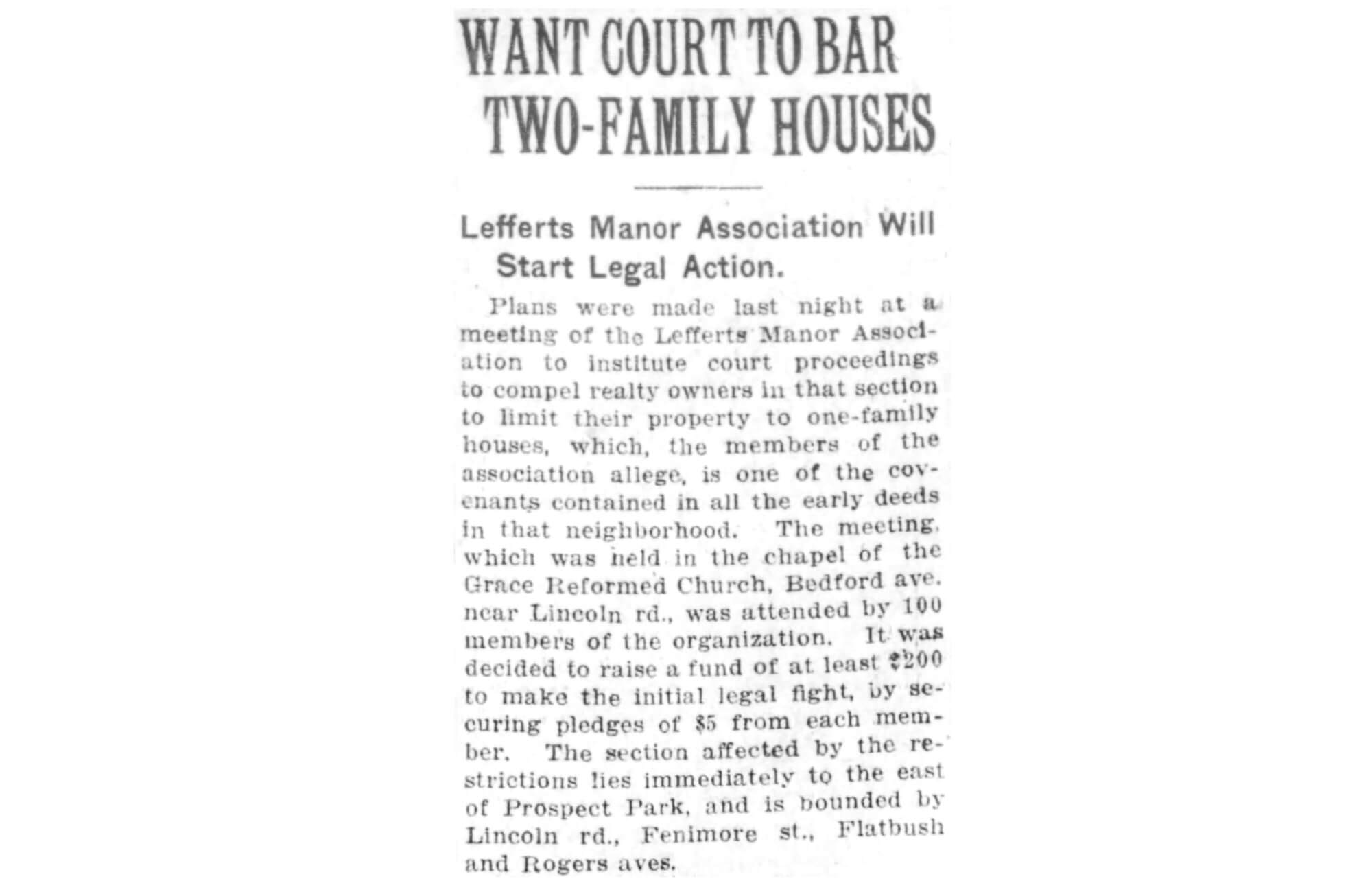

Two-family rowhouses, which look exactly like traditional one-families from the street, were being built all around them, outside of the manor boundaries, so a couple of the developers tried to sneak some two-families past Lefferts. He sued them for disregarding his covenant and won. Every time. After the buildings were sold to homeowners, a couple of them tried to rent rooms, or subdivide. James Lefferts sued them too and won. His single-family covenant was rock-solid.

James Lefferts died in 1915. At that time, only about half of Lefferts Manor was completed. The Manor would not be fully built out until the 1930s. Architectural styles changed, and the Renaissance Revival row houses were joined by Colonial Revival houses, both in red and pale yellow brick. The iconic Tudor-Revival half-timbered row houses on Rutland Road and Chester Court (outside of the Manor) were also built. These were all one-family, as well. Many of the later homes had garages!

The Manor’s restrictions were taken up by the Lefferts Manor Association, a homeowner group established in 1919, the same year the Lefferts Homestead was moved from Flatbush Avenue to Prospect Park, where it remains today as a house museum. The LMA was organized to unite homeowners in various civic and neighborhood projects, but its main focus was in enforcing the Manor’s covenant to remain a community of single family homes.

They had their work cut out for them, especially as the world changed around them. The Great Depression was a valid reason for some homeowners to want to rent out rooms. But whenever the LMA found out, they threatened court action, and if the case went to court, they always won. By the 1930s, more and more Jewish, Italian and Irish families moved into the Manor. They were not all welcomed by some of the old-time Manorites, but they all endured and adjusted. After World War II, Caribbean American and African American families also began moving to the Manor.

As in all of New York City, many people were beginning to flee the city for the new suburbs in Long Island, aided in part by the G.I. Bill and new highways. The black newcomers; civil servants, teachers and other professionals just like their neighbors, sometimes found resistance from some of their neighbors too, but for the most part, were welcomed into the neighborhood as well. They were asked to join the LMA, which had black officers and members as far back as the 1950s.

During the 1940s and ‘50s, some of these homeowners, of all persuasions, tested the boundaries of the covenant by trying to subdivide their homes. They all failed. Some owners tried to claim that they were being discriminated against. Restricted covenants that discriminated by race or religion were being challenged in courts across the country. In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that such restrictions violated the 14th Amendment and were illegal.

Locally, this upended racially restricted covenants that were used to exclude black homeowners from buying in upscale enclaves in Queens.

Here’s where Lefferts Manor’s restricted covenant was different. It did not prohibit anyone from buying based on race, religion or ethnicity, it only barred homeowners from subdividing their property. Unlike many other restricted covenants, this one was not about race. Buyers knew Lefferts Manor was single family when they signed the deed. If they wanted a house they could subdivide, they could buy outside of the Manor, which was only eight small blocks within Prospect Lefferts Gardens, within Flatbush, within Brooklyn.

The covenant would be challenged again. In one case, the Dept. of Buildings signed a permit allowing an owner to covert his house to a two-family. The Lefferts Manor Association took him to court, and the court overruled the DOB, stating that the covenant pre-dated the permit, and was upheld by law. Soon after, in 1979, a large part of PLG was landmarked, including the entire Manor.

Today, Lefferts Manor remains special – the only single family enclave of houses in Brownstone Brooklyn, a neighborhood that remained economically stable, racially integrated and fiercely committed to maintaining its special flavor and history. This year, 2019, is the centennial of the Lefferts Manor Association, still upholding the covenant made between James Lefferts and the first homeowners of Lefferts Manor. Centennial celebrations have been planned for September.

Related Stories

- The Lefferts Family, Flatbush Branch

- How the House Tour Has Changed in PLG (It’s Coming Up This Weekend)

- Past and Present: Tennis Court

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment