If This House Could Talk: Life on Jefferson Avenue

The grandson of political pioneer Bertram L. Baker recounts how growing up on Jefferson Avenue in the mid 20th century shaped who he is today.

Brownstones on Jefferson Avenue. Photo by Susan De Vries

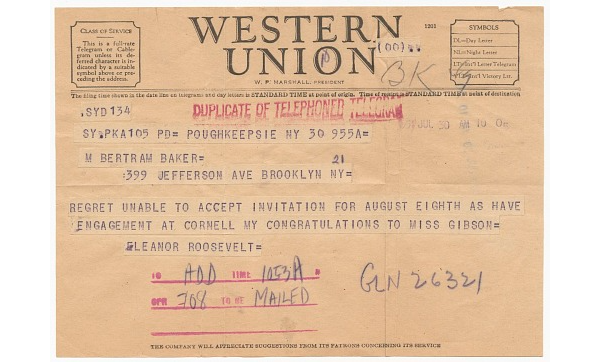

Here I am, 76 years old, grandson of the late Bertram L. Baker, the political pioneer who in 1948 became the very first Black person elected to office in the history of Brooklyn. Many tens of thousands of Blacks had lived in Brooklyn through the 1800s and into the first half of the 20th century. But it was this immigrant, born on the then British colony of Nevis in 1898, who made Brooklyn history, as the Black political pioneer. Think of it. I write this in January, 2026, when Brooklyn has scores of Black elected officials, in both houses of the state legislature, in the City Council, and in the U.S. Congress.

Bertram Baker meant everything to me. Sometimes I say that had it not been for him and his wife, Irene Baker, I would not have survived as I did. In 2018 I wrote a memoir about him, “Boss of Black Brooklyn: The Life and Times of Bertram L. Baker,” published by Fordham University Press.

My grandparents took me and my polio stricken mother into their brownstone home at 399 Jefferson Avenue in 1952. We had been living in the Fort Greene projects with my father, Wilfred Howell, a Black World War II U.S. Marine veteran and would-be lawyer, who was sinking deep into alcoholism and did not show up at home to take care of me or my mom. (I came in the coming decades to love my father, who became a member of Alcoholics Anonymous, and about whom I wrote tender remembrances after his death in 1993 at the age of 73.)

Over at No. 399, I lived like a prince. Oh, I knew the streets of Bed Stuy were being spoken of by whites as a Black ghetto rising. (Historian Harold X. Connolly would later describe these years in his book about Bed Stuy, “A Ghetto Grows in Brooklyn.”) Our brownstone appeared in my eyes and mind as a castle, but it existed in some tough times.

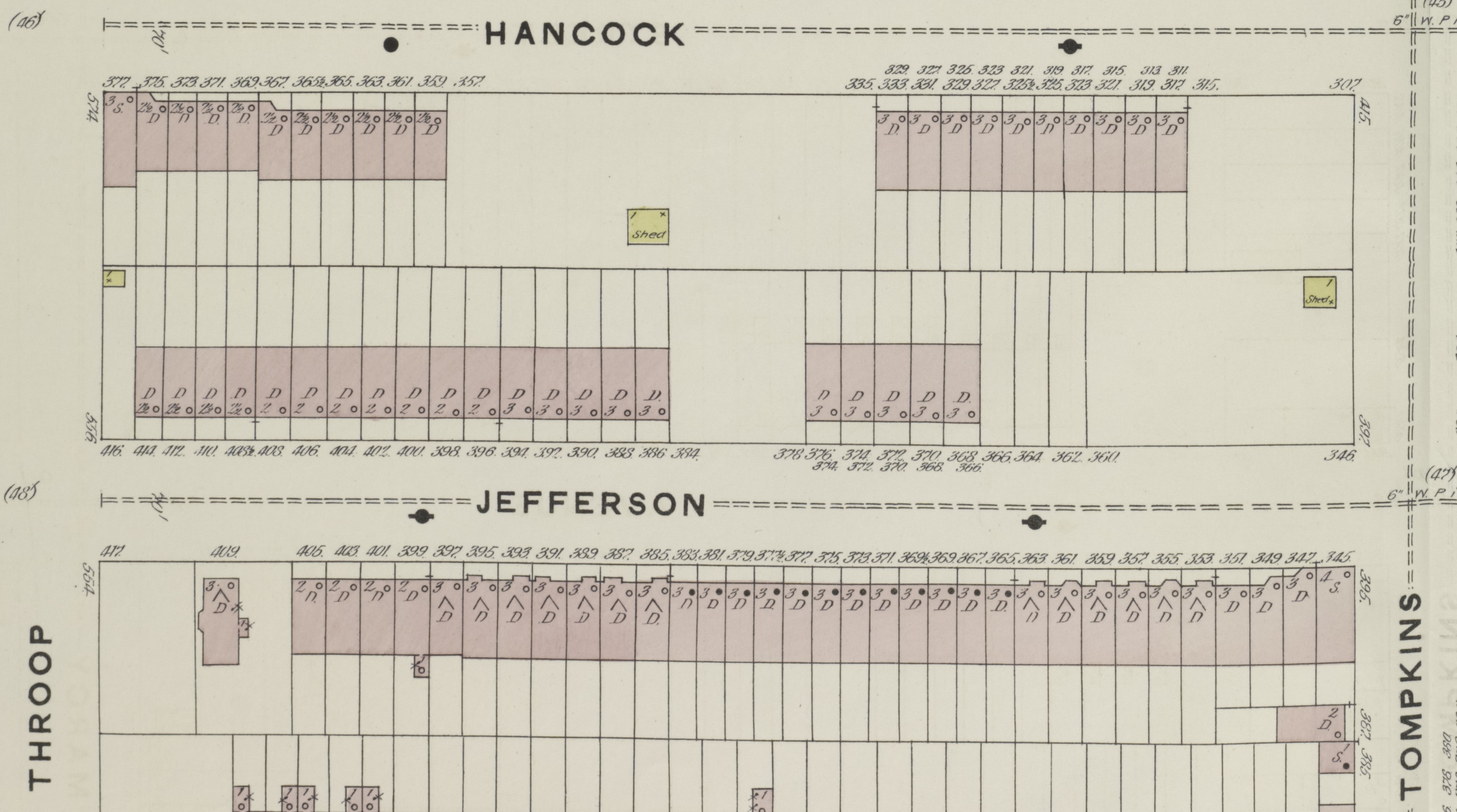

Yes, almost everyone on the outside, especially whites, called it a ghetto. I had friends who became heroin addicts, one who was shot by police during the riots of 1964, others who were victims of gang violence. But living at 399 Jefferson Avenue in the 1886 Neo-Grec three-story Baker brownstone shielded me from it all. Bertram Baker was known by those Blacks who hustled in Central Brooklyn politics in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s as the “Chief.” That term came from the old Tammany Hall crew that dominated New York Democratic politics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Bertram Baker did not have a reputation for demanding under-the-table payoffs for favors, but he was clearly intent on getting civil service jobs and, yes, judgeships for those loyal ones who were in his political club. This was the United Action Democratic Association over at 409 Hancock Street, a block from 399 Jefferson Avenue.

I, of course, have my own personal memories of Bertram Baker and 399 Jefferson from my childhood. My grandfather’s home office with its well-preserved original flooring was on the second floor facing the backyard. There was an adjoining parlor with a fireplace and windows facing the active street outside.

Besides seeing all the first Black Brooklyn judges and first Black officials in the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office coming to meet with my grandfather, there were events that stood out. First, let me point out that, in addition to being a Black Brooklyn political big shot, Baker from the late 1930s through the late 1960s was the executive secretary, the top administrative official, with the American Tennis Association. This was the national Black organization that organized and ran across-the-nation tournaments and social gatherings for Blacks smitten by the sport, which otherwise was all-white.

Baker used his clout and skills in the early 1950s to get the national and international white tennis competitions to open their doors finally to a person of color to play on the world stage. The moment of historic importance came in 1957 when Althea Gibson rose to stellar heights, forever erasing the image of tennis as a whites-only sport. Gibson won the women’s singles tournament at Wimbledon in England, and the Black world cheered.

Returning to New York, Gibson came to 399 Jefferson Avenue to celebrate her victory, acknowledged around the globe in newspapers, radio stations, and on television. Baker gave a toast to the new queen of tennis and drank highballs of Old Grandad whiskey and ginger ale as he slapped backs and made the most of the moment, as I wrote in “Boss of Black Brooklyn.” Gibson sat next to him at the dining room table with Baker’s family, including his then eight-year-old grandson, me. Black Brooklyn was happy.

In the coming days, Baker rode in the limousine with Gibson in the ticker tape parade thrown by then Mayor Robert F. Wagner in her honor. They waved as the parade moved along Broadway and television cameras recorded it all for history.

Changing Demographics.

The Baker family bought 399 Jefferson in 1942 for slightly over $5,000 from the Gardner family. One thing of special note to me about the Gardners was how they represented the Irish, who were significant in the demographics of old Bed Stuy. Ties that bind me and the Gardners (none of course having to do with ethnicity or even politics) were that the Gardners were devout members of Our Lady of Victory Roman Catholic Church.

This, Our Lady of Victory Church, was where I served as an altar boy for several years, from the late 1950s until I graduated from Our Lady of Victory grammar school in 1962. I remember no white students at all from my time there. The age of the Irish Gardners was behind us, as ethnic whites became a thing of the past throughout Bed Stuy. On my 399 Jefferson Avenue block, there was only one white resident remaining in my childhood years, an elderly Irish lady, whom I never got to know.

The church’s demographics changed dramatically in the early to mid 1900s, from the Irish who were dominant in 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, to the native-born Blacks and West Indians who began moving into Victory’s surrounding Bedford Stuyvesant community.

Brownstoner columnist Suzanne Spellen – perhaps the most published lover of Black Brooklyn architecture and neighborhood history – wrote about the history of Our Lady of Victory on the occasion of its 150th anniversary. Though no longer a practicing Catholic, I attended that celebration and felt pulled back into the history of the church.

Before Bertram Baker.

As I was collecting bits of details for this Brownstoner piece, I was told by several skilled Brooklyn historical researchers of Brooklyn homes that finding original architects and developers for specific houses, especially brownstones from the 1880s, is extremely difficult. But there are some who have been diving into this, including Morgan Munsey. Real estate agent, preservationist, and lover of Bed Stuy history, he recently told me that when he takes folks on tours of Bed Stuy’s streets, he always stops at 399 Jefferson and lets them know about Bertram L. Baker.

He wrote to me by email that 399 was developed by William Reynolds and that the architect behind the project was Isaac D. Reynolds, though he didn’t believe they were related. Isaac Reynolds designed numerous buildings in Bed Stuy. William Reynolds, who resided on Madison Street near Stuyvesant, had a son, also named William Reynolds, who at the age of 25 became the youngest state senator ever elected in New York.

Research shows that No. 399 was built circa 1884, and sold to the first owners in 1885. This, by the way, is far from what the city Department of Finance has been saying in its outreaches to me regarding taxes, that 399 was constructed in 1915.

Now let’s keep looking at 399 Jefferson, but go further back in time. Some of it’s funny. Some not. The brownstone at 399 Jefferson had a diverse line of owners in its history, and here’s a glimpse.

Before the Irish Gardners were at our Bedford section brownstone, there was the Dutch Sansom family.

The Times Union of Brooklyn reported on June 27, 1910, page 9: “A very pleasant afternoon was spent at the home of Mr. and Mrs. John H. Sansom, 399 Jefferson Avenue, on June 24, in honor of the fourteenth anniversary of their marriage. . .The guests comprised the young friends of their only daughter Alice, who was hostess,” and all recited “The Dutch Lullaby,” soon to become the popular song “Winken, Blinken and Nod.”

“The Dutch Lullaby” was a poem for children, and the newspaper carried an illustration of the partying young ladies at 399 that day.

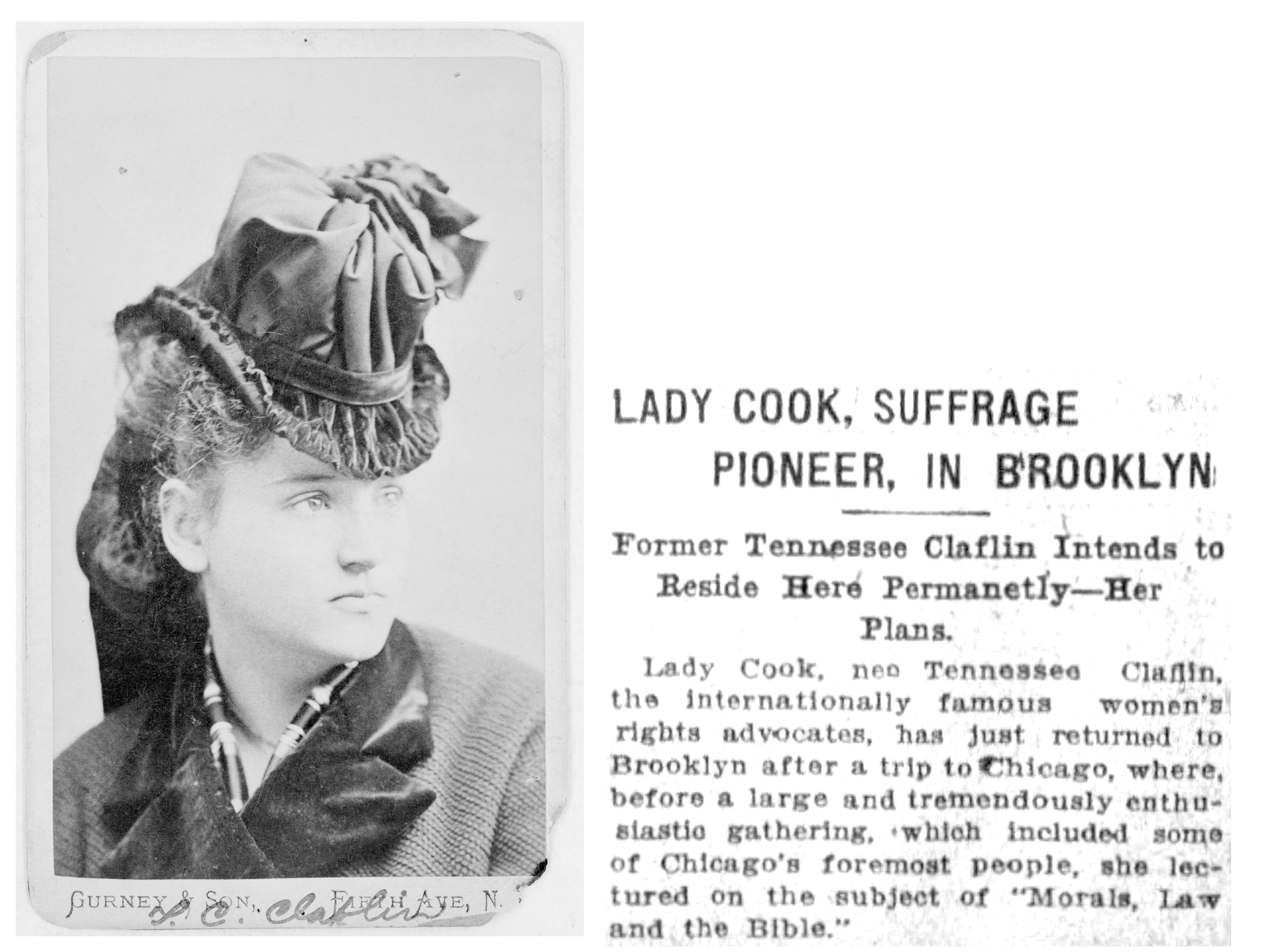

Bertram Baker would have been astounded if he’d learned at any point while he lived at 399 that one past resident of the house had been Tennessee Claflin, born in Ohio in 1844, one of the most controversial ladies of post-Civil War America. And she was quite literally a lady. In 1985, while in England, she married Sir Francis Cook, a wealthy Britisher who gave “Tennie,” as she was known to friends and family, the life she’d always longed for. Sir Cook, several decades older than Tennie, died in London in 1901, and 10 years later she sailed back across the Atlantic to continue what she called her life missions — notably women’s suffrage.

In 1911 she went to live at 399 Jefferson Avenue. Some — most notably among them biographer Myra MacPherson — would say Tennie’s sexiness played an important role in her life. In 2014 MacPherson wrote a well-received book about Tennie and her sister, Victoria Woodhull, titled “The Scarlet Sisters: Sex, Suffrage and Scandal in the Gilded Age.”

Let it be known that I had learned about Lady Cook and 399 Jefferson Avenue quite a while before I learned of MacPherson’s book, and I should tell you that the book mentions nothing of 399 and little about Brooklyn. But 399 resident Lady Cook was part of the Gilded Age in Brooklyn. She had known and done business with, through the late 1800s, tycoons, including “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, considered to have been one of the wealthiest Americans in history.

Highlighting 399 Jefferson Avenue, The Daily Times (of Brooklyn) ran the following article on October 11, 1911:

LADY COOK, SUFFRAGE PIONEER, IN BROOKLYN

FORMER TENNESSEE CLAFLIN INTENDS TO RESIDE HERE PERMANENTLY — HER PLANS.

“Lady Cook, nee Tennessee Claflin, the internationally famous women’s rights advocate, has just returned to Brooklyn after a trip to Chicago, where, before a large and tremendously enthusiastic gathering, which included some of Chicago’s foremost people, she lectured on the subject of ‘Morals, Law and the Bible.’

“Lady Cook, who resides at 399 Jefferson Avenue, intends to make her home permanently in this borough.

“Lady Cook, who is now advanced in years, was the pioneer worker in the cause of women’s rights. In spite of persecution, defamation, arrest, etc., Lady Cook has stuck to her colors through all the years, and today is more enthusiastic than ever.

“In the first part of October she intends to lecture in the Academy of Music, Brooklyn. Lady Cook has all her life paid her own expenses on her various tours, never accepting a financial donation from anyone. There is hardly a society in New York or London which has for its purpose the betterment of the human race that has not known her beneficence. Her health is in a precarious condition, and she never lectures without having several medical attendants present.

“After her lecture in Brooklyn she hopes to speak in Philadelphia, and then lead a delegation of the leading women of the country to Washington, to demand the vote on the grounds that the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the constitution give every citizen who is neither an idiot nor a criminal the right of suffrage. This was the same plea that she and her sister made in Washington in 1872. At that time a minority report of the Congressional Committee in charge sent in a favorable opinion. The majority report was to the contrary, however, and the bill was never passed.”

But nothing about Lady Cook was permanent. She went back to England for a brief while, returning in 1912. The Brooklyn Eagle, in its December 12, 1912, page 20 article, reintroduced her this way: “Lady Cooke (sic), who was Tennessee Claflin, owner of millions and lecturer on suffrage for women, arrived here today on the steamship Oceanic, and went to the home of M. F. Sparr, at 399 Jefferson avenue, Brooklyn.”

M. F. Sparr, by the way, whose first name was Mary, was a sister of Lady Cook and Victoria Woodhull, and from my searching on ownership/occupancy records, she actually lived at 341 Hancock Street, one block to the south of Jefferson Avenue. Mary Sparr obviously was the key holder at 399 Jefferson, though neither she nor Lady Cook are listed anywhere I’ve seen as owners. Even so, they are both the part of the story of 399.

Living on Jefferson Avenue.

No. 399 became my refuge. My bedroom was right next to my grandmother’s and grandfather’s. The room had an old upright closet, which sat behind my bed’s headboard. The way I slept, facing the single window with dark mahogany window frame, I felt I could see the whole world beyond.

The brownstones ruled. All the houses around us were three or four stories. Later in life, as an adult, I felt I would fight, if need be, to prevent the demolition of those homes and the erection of tall apartment buildings in their place. I became a preservationist, a lover of landmarks, even though I’ve never really been an activist.

My grandparent’s bedroom had an old fireplace in it, as did the living room on the second floor. As a kid, I could feel, as it were, the 19th century. My mother’s bedroom faced the backyard, where our German Shepard romped and barked.

As for living with a grandfather who was the Boss of Black Brooklyn, there were many perks I gained with that. I was always treated well by the politicians, even judges who bowed to him. I guess I took it all for granted.

It was my grandfather who decided I should go to the Catholic all-boys Jesuit high school, Brooklyn Preparatory. Old Brooklyn politicians, especially Irish, had sent their sons there, and soon it became my secondary-school home. I did well and that made Bertram Baker proud.

In the end, the end being here, I have to say I would have accomplished little in life if my grandfather had not been there.

More recently, while renting out 399, I have lived in a landmarked home near Prospect Park that is more than a century old. Like my Bed Stuy house, it sits on land that once belonged to the old Dutch slave-holding Lefferts family. That landmarked house is meaningful to this born-and-raised Brooklyn-loving guy — but it does not hold a candle to 399 in my spirit. I always tell friends and family there’s no way I would ever consider selling my Baker family brownstone.

What I hope is that I can one day get it placed in the National Register of Historic Places, and now, retired several years from my very last job (teaching journalism at Brooklyn College), I want to see its history preserved. And if I have a last wish, apart from the well-being of my immediate family, it will be that 399 Jefferson Avenue is appreciated well into the future by those in Bed Stuy and those moving there. And, as demographers and spirit readers tell us, that latter number seems never ending.

Related Stories

- Our Lady of Victory Catholic Church Celebrates 150 Years in Stuyvesant Heights

- Producer Charles Hobson Remembers ‘Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant’ on Its 50th Anniversary

- A Walk Through Shirley Chisholm’s Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on X and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

Great article Ron—I’m glad that you’re a neighbor.