Producer Charles Hobson Remembers 'Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant' on Its 50th Anniversary

The public-affairs television program aimed to counter negative stereotypes and premiered in April 1968 on Channel 5 in New York City.

‘Living with the El’ shows children in the 1940s in Bed Stuy. Photo by Joe Schwartz via Joe Schwartz Photo Archive

When Charles Hobson was growing up, the stretch of Hancock Street between Nostrand and Marcy Avenue he called home felt like a close-knit, homey place. Born in 1936, the former television producer and documentarian recalls a block that had, along with his parents, immigrants from the West Indies and Jamaica, people from Barbados, a few other Jamaicans, plus his two white neighbors: On one side was a dentist and wife; on the other an Irish guy named Corcoran who looked like “he hadn’t had a haircut in 20 years.”

The area’s numerous churches were a point of connection. Hobson would regularly walk with his mother to the Concord Baptist Church on the corner of Marcy Avenue and Madison Street, a few blocks away, and he remembers Reverend Milton A. Galamison, a local pastor at the nearby Siloam Presbyterian Church, who was revered among his neighbors for his persistent activism. There were jazz clubs, and the sports teams at the historic Boys High School, where Hobson attended and ran track.

“It felt more residential back then,” Hobson says. “It was an interesting community.”

It was this atmosphere that Hobson wanted to bring to screen with “Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant,” which premiered in April, 1968. The public affairs television program, which aired for only two years on Channel 5 (then WNEW before it was purchased by Rupert Murdoch in 1985), aimed to capture a realistic portrait of the neighborhood that countered negative stereotypes in the wake of local riots in 1964 after a 15-year-old African-American boy was shot and killed by a white police officer in Manhattan.

“We were trying to reach black folks,” Hobson says. “There was nothing else.”

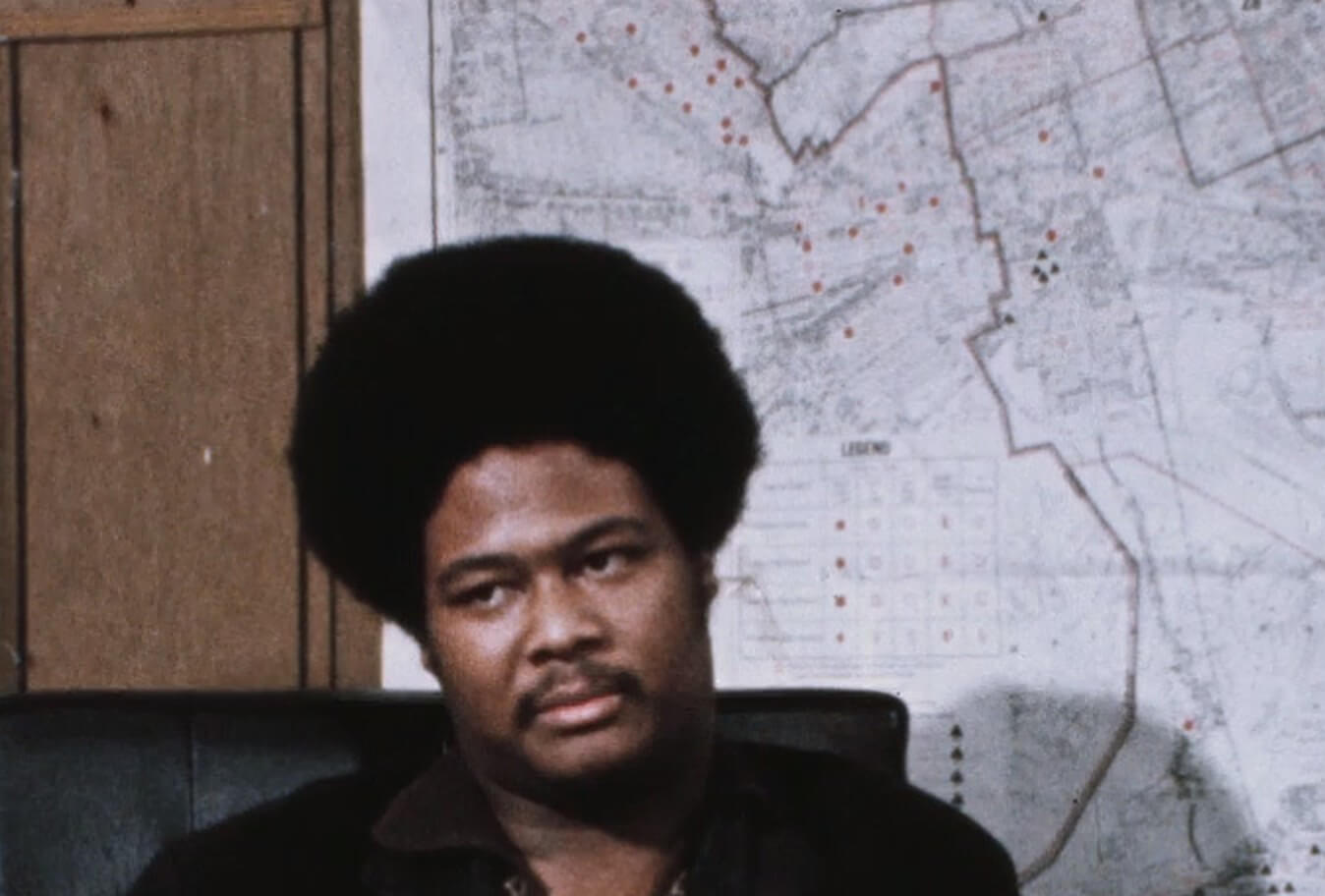

Hosted by Jim Lowry and Bed Stuy resident and actress Roxie Roker (mother of the singer Lenny Kravitz and most famous for her later role as Helen Willis on the 1970s television sitcom “The Jeffersons”), each episode, clips of which you can find on YouTube, combined on-the-street reporting with interviews, performances and community forums that were directly pitched to local issues, all presented with a casual intimacy.

“Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant” aired in both the 1 a.m. and 7 a.m. time slots, which made the show difficult to see. “But we still had an audience,” Hobson says. “We got a lot of letters. People knew about us.” And its reputation has only grown in the years since its arrival. The program was among a number of shows produced explicitly for an African-American audience around that same time. Hobson would go on to contribute to the first two seasons of the more well-known “Black Journal,” which premiered on WNET in June 1968 and had a higher budget (a reported $500,000 per season as opposed to the $45,000 given to “Bed-Stuy”) and a national focus. He was also the original creative force behind the long-running “Like It Is,” a morning current affairs program hosted by Gil Noble. Premiering the same year were the variety series “Soul!” and the Boston-based “Say Brother.”

Hobson didn’t originally have anything to do with “Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant.” The origins of the show reside with the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation. Launched in 1967 by Robert F. Kennedy in collaboration with local activists, the BSRC was the country’s first community development corporation, and one of its first projects was a television program to promote the neighborhood (co-host Jim Lowry was a BSRC staffer). But the group’s initial choice to produce the show, a local children’s book author and friend of Hobson’s named Leslie Lacey, quickly tried to back out. “I can’t work with these white people!” Lacey told Hobson over the phone, referring to the Kennedy staffers who were involved in the production. “I went to a meeting with the group, and it was pretty clear that I was the only person there who knew anything about Brooklyn,” Hobson says.

Following his graduation from Brooklyn College in 1960, and after spending time in the United States Army, Hobson began working at the radio station WBAI, first as a host and later as a producer. But when he moved to television production, he had to learn on the job. “There was very little money,” he remembers. “And because of that, things could happen naturally.”

This led to an improvisational, haphazard mode of working, Hobson says. If a guest didn’t show up for a shoot, they would take the cameras to the nearest park and talk to whoever was around; when it rained, there was no time for delays and the hosts would have to use umbrellas while filming their segments. The crew were able to get interviews with well-known figures such as Harry Belafonte and New York Mets left fielder Cleon Jones, but just as important were episodes that focused on welfare mothers who needed extra support, young draft dodgers, Pratt professors and black police officers. One of Hobson’s favorite pieces was an interview with an old retiree known around the neighborhood for his love of music who, unbeknownst to the crew, turned out to be the composer Eubie Blake, who cowrote “Shuffle Along,” one of the first Broadway musicals to be written and directed by African-Americans.

Hobson would later leave Brooklyn, and “Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant” is merely a blip in his career—he later won Emmy Awards, produced projects for both PBS and BBC, lectured at universities across the world and was a Fulbright Scholar. When he moved back to Boerum Hill around 1995, he found much of what he remembered had changed. Which makes him thankful that the show existed at all, and that in the years since its original run it has developed an audience that recognizes its importance.

“There was no other black community in the country that had this kind of documentation,” he says. “It was a remarkable thing.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2018 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- The Mundane and Surreal Come Together in the Work of Brooklyn Artist Leigh Ruple

- The Radical Women Excluded From Art History, Now on View at the Brooklyn Museum

- Egg’s George Weld Keeps It Local

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment