Landmarking vs. Demolition: What Work Can Be Done While Permits Are Processed?

It’s a drama that plays out time and again in Brooklyn: An application for a demolition permit is filed for an historic building, spurring the community to rally around it and push for its designation as a landmark.

Demolition in Red Hook. Photo by Susan De Vries

It’s a drama that plays out time and again in Brooklyn: An application for a demolition permit is filed for an historic building, spurring the community to rally around it and push for its designation as a landmark.

By that time, it’s usually far too late. But not always.

Recent examples of such a clash include 441 Willoughby Avenue in Bed Stuy, where residents are still hoping to get the 120-year-old French Gothic home in front of the Landmarks Preservation Commission before a pending demolition permit is issued. The 130-year-old Grand Prospect Hall in Park Slope is being demolished after failing to secure landmarking. Boerum Hill’s Gothic Revival Church of the Redeemer was razed and the site now holds 63 apartments. Bushwick’s Charles Lindemann House was built in 1890 and approved for demolition in 2019.

A former kindergarten and a related building at 236 and 238 President Street in Carroll Gardens are a rare last-minute landmarking success story. A developer reportedly planned to buy one of the properties and raze it for condos, but never actually filed an application for a demo permit before the 19th century buildings were landmarked, thanks to overwhelming support from the community, local politicians and Joan Baez. The Downtown Brooklyn home of 19th century abolitionists at 227 Duffield Street-Abolitionist Place was also saved from demolition at the last minute by the intervention of Mayor de Blasio, but only after years of effort by local preservationists to protect it.

So when an application for a demolition permit is filed, what exactly does that mean for landmarking efforts and what work can building owners do while they wait for the city to issue a permit?

When a demolition permit is filed and the building is not landmarked

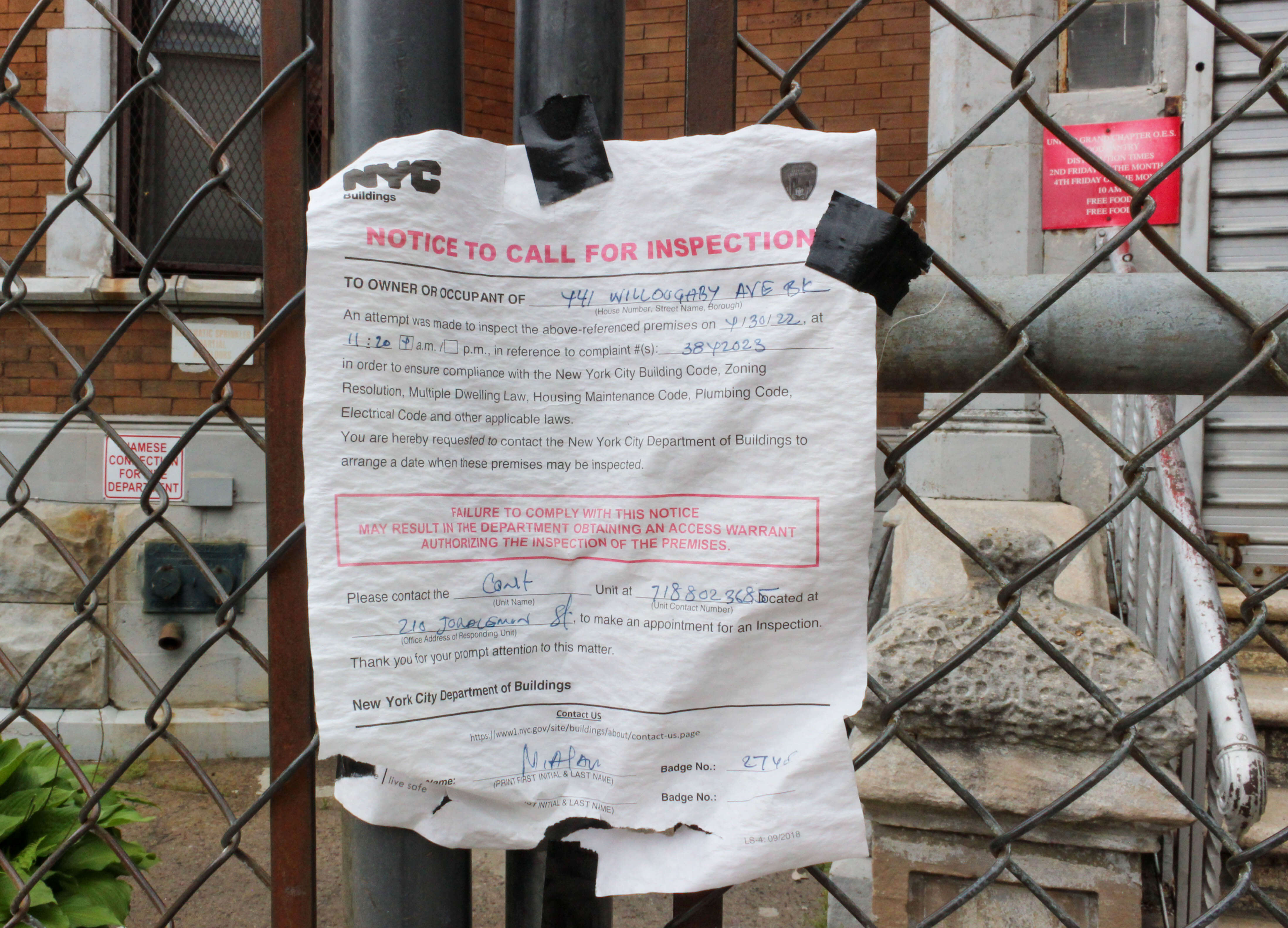

When a demolition permit is filed with the Department of Buildings, owners have to make sure the countless forms and requirements are in line, otherwise the process hits speed bumps from the start (such is the case for 441 Willoughby Avenue, with DOB saying the building owner needs to submit further documentation before permits can be approved).

In an ideal world for developers, the DOB will review a demolition permit in around two business days, and then schedule a development inspection within another two business days. However, DOB spokesperson Andrew Rudansky says the timeframe is dependent on when applicants submit all the required documentation.

While building owners wait on permits, they cannot make any alterations to the building that require any kind of permit, such as removing walls, changing exits or altering plumbing — which would all require alteration permits. They are free to do any work that doesn’t require a permit, including landscaping and removing trees and small backyard storage sheds.

Rudansky said community members could check on what alteration and new building permits a developer had through the DOB Now portal, but added all demolition permits are still filed in the department’s old Building Information System.

“If a member of the community believes unpermitted construction or demolition work is occurring at a building, we strongly encourage them to let us know about it by filing an official 311 complaint,” he said, adding that DOB responds to 311 complaints about illegal demolition within 24 hours. If construction or demolition work is being performed without a permit, DOB can issue a stop work order at the site and carry out further enforcement, he added.

A full stop work order prevents all construction and demolition work from occurring on a site until owners and contractors remediate violations and DOB can make a determination that work is safe to resume, Rudansky said. If the owners and contractors fail to correct the violations, the stop work order can remain indefinitely.

In the cases of 441 Willoughby Avenue and the Grand Prospect Hall, Rudansky said DOB had received 311 complaints on suspected unpermitted work, but inspections didn’t turn up anything illegal.

The last-ditch effort to landmark

Successful landmarking efforts can take years, often requiring a fight from a sizable group of passionate and committed locals with the support of their local City Council member. Examples include the Bedford Historic District, the Crown Heights historic districts, PLG’s Chester Court Historic District, East New York’s Empire Dairy and the recently designated East 25th Street Historic District in Flatbush.

For those wanting to protect an historic building from demolition — even after an application for a demolition permit has been filed — landmarking is pretty much the only option. Of course the building has to fit the LPC’s criteria, which includes a building having to be at least 30 years old and having a special character or historical interest, and it can only be protected once it is officially designated.

To get it there, a Request for Evaluation can be filed by anyone in the community. In the case of 441 Willoughby Avenue, neighbors got word a change of ownership could be in the works and filed an RFE in January 2022, months before the demolition permit was filed in March.

However, LPC has no designated time frame for how it evaluates RFEs, so the process essentially becomes a race between when demolition permits are signed off on and when — and if — the LPC agrees to calendar a building for a hearing and move forward in the lengthy designation process.

Even before making it to the calendar for a public hearing, the building must be evaluated by the agency to see whether it is a “potentially meritorious [property] in light of agency priorities” and, if it is judged as being so, all LPC commissioners must vote on whether to bring it to a public hearing. Calendering it for a public hearing is the first formal step in the process, and the first step at which a building slated for demolition could get some protection.

LPC spokesperson Zodet Negrón told Brownstoner that when a property is calendared for a designation hearing, the owner can still do work on the property with no review by LPC. However, if the owner needs a permit from DOB, the DOB notifies the LPC and DOB will not act on the application for 40 days. After the 40 days, during which LPC must decide upon designation, the DOB is required to make a decision on the permit, Rudansky said.

Negrón added: “During these 40 days, the LPC can choose to designate the building if the proposed work is deemed harmful. If LPC designates the property, the owner must get approval from the LPC. If the LPC doesn’t designate, the owner can obtain the DOB permit after 40 days and do the work.”

Negrón added that designation after a DOB permit had been issued did not invalidate that permit, and the owner could continue to do the approved work without getting LPC approval. “LPC only has formal jurisdiction over work on a property when it is designated.”

Negrón said that if community members were concerned about work being done at a landmarked or calendered property, they should contact LPC and DOB. However, she added that if a property owner had that permit before calendaring, they would be able to proceed.

Related Stories

- Excavator Tears Into Bed Stuy’s Pre-Civil War Carpenter Gothic Church Thursday

- Residents, Pols Rally for Preservation of Bushwick Avenue Landmarks Ahead of Demolition

- Shaken by Recent Decisions, Preservationists Say Landmarks Commission Is Not Doing Its Job

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment