At Gowanus Canal Superfund Town Hall, Residents Were Eager to Hear of Progress

In a small, crowded space at the Wyckoff Gardens Community Center in Boerum Hill Thursday night, dozens of residents waited patiently to hear what the Environmental Protection Agency had to say about the cleanup of the nearby Gowanus Canal Superfund site.

View of the Gowanus Canal from the Union Street Bridge. Photo by Susan De Vries

In a small, crowded space at the Wyckoff Gardens Community Center in Boerum Hill Thursday night, dozens of residents waited patiently to hear what the Environmental Protection Agency had to say about the cleanup of the nearby Gowanus Canal Superfund site.

The current sewer system is not adequate for existing residents and locals worry what will happen if the area is rezoned for development, as de Blasio seems to favor. For many people in attendance, it has been a long process of getting to this point.

“Like many of you here today, I have been working on this issue since 2000,” said Congresswoman Nydia Velazquez, who began the meeting with opening remarks.

Valazquez told the crowd that the cleanup funding for 2017 was $1.08 billion and that the federal government was on track to approve a similar amount for 2018. Or, she added, “maybe even higher.”

New York State Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon and the EPA’s regional administrator Pete Lopez followed with their own comments for the audience, stressing the importance of community engagement and their eagerness to hear from the residents in front of them.

Natalie Loney, the Community Involvement Coordinator for the EPA, led the agency’s presentation with some historical background.

“Much of brownstone Brooklyn can be traced to the Gowanus Canal,” she said, highlighting the path through which housing materials made their way to the borough’s neighborhoods.

Soon enough, the conversation turned to the present. There was a discussion of the need for the controversial CSO tanks, explanations of the black mayonnaise that floats up from the canal’s surface, and even images of the famous swimmer—who, according to Loney, told her the contaminated water “tasted like baby diapers and gasoline.”

The CSO tanks — aka combined sewage overflow tanks — will absorb sewer-system overflow during storms to reduce (but not eliminate) the amount of raw sewage flowing into the waterway.

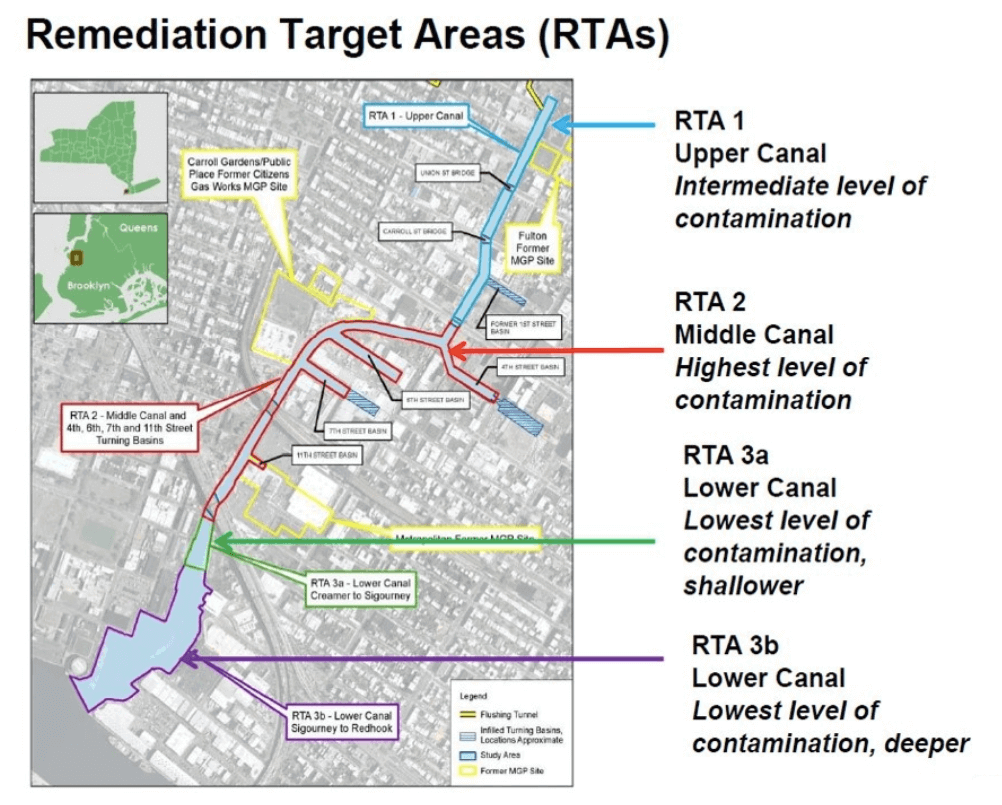

Walter Mugdan, director of the EPA’s Emergency and Remedial Response Division, took over to explain some of the details of the project. Specifically, he outlined the Record of Decision that was initially drafted in 2013, breaking it down into six distinct sections in which the order of cleanup will proceed.

First, there will be the dredging of soft sediments, better known as the black mayonnaise. This is the most toxic sediment of the canal and will be disposed of off site, according to the presentation.

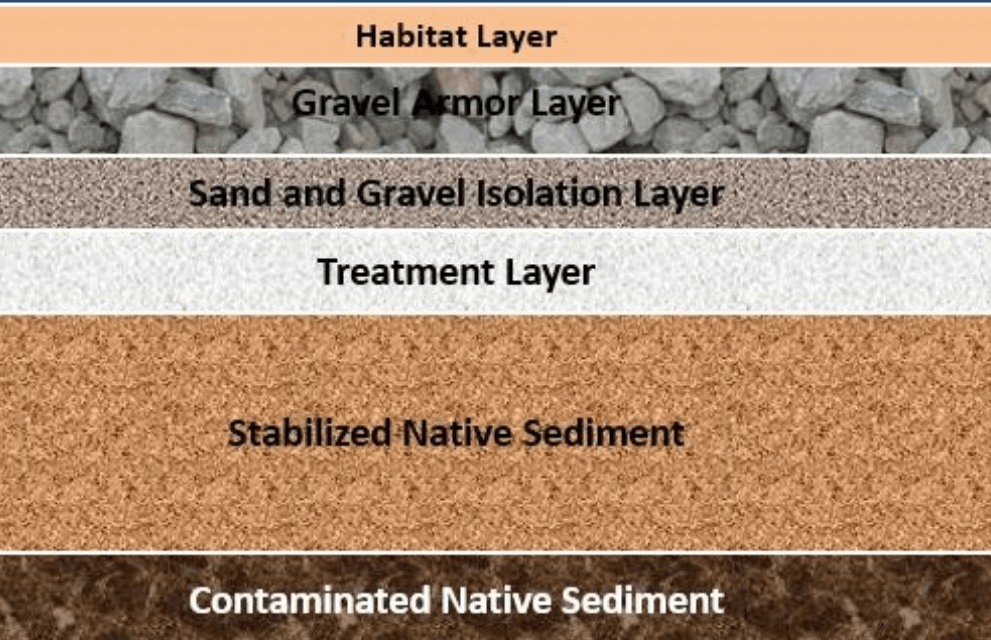

After that, there will be a cap placed down over the native sediment, to keep out toxins which have seeped below the soft sediment, followed by what the EPA is calling targeted, in-situ stabilization, which is essentially drilling down into problem areas and adding a combination of cement and sand to create another sediment layer.

The image above, which was part of the EPA’s presentation, gives a better sense of how all these layers of sediment will look.

While the dredging is occurring, there will be a cleanup of the sites that formerly housed manufactured gas plants, including Thomas Greene park at 225 Nevins Street. A temporary pool will open while the park is closed, officials said.

The EPA assured the residents that the park would be rebuilt and modernized by the end of this procedure.

“It would be silly not to take that opportunity to improve facilities for the community,” Mugdan said.

It is at that park where the EPA initially advised the city to place the larger of the two CSO tanks they say are necessary for the sustained preservation of the canal. But after community backlash, the city is considering placing the larger tank on nearby land, as can be seen below.

The problem is that the second area is not owned by the city. They would have to work out a deal with the owner or seize the lot by eminent domain.

Last week, concerned residents sent along a press release urging Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams to stop the proposed demolition of the Gowanus Station building at 234 Butler Street, which they say has significant historical value.

Sal Tagliavia, the owner of 234 Butler Street, where the EPA has advised to put the larger of their tanks if they cannot have it under the park, spoke at the meeting about his building.

“That’s a beautiful picture of my building that says ‘save me,'” he said, referring flyers that were passed around the meeting. “But what about my business? My tenants? My employees? Our families? What’s gonna happen to them? New York City hasn’t really done anything to approach us or notify us.

In 2015, Alloy Development proposed to build two 104,000 square foot office buildings at both 234 Butler Street and 242 Nevins Street. After it was announced that the city wanted to seize the land through eminent domain, they suggested a plan to donate a portion of the land, which was rejected.

The second, smaller tank will be located along the 4th Street Basin, near the Whole Foods at 214 3rd Avenue.

No decision has been made yet on the locations, and the EPA has given the city a deadline of four years in which they can acquire land. If not, the larger tank will have to be built under Thomas Greene Park.

According to the EPA, they hope to begin the first phase of cleanup by 2020 but were hesitant to declare a date of completion due to setbacks that are bound to occur. Estimates say total cleanup could take approximately eight to 15 years or so.

The residents who spoke during the meeting had concerns: about the sustainability of the sediment cap (it will apparently last nearly 100 years); if the CSO tanks will be harmful (the EPA claims they will not be); and raw sewage smell around the community (it will, unfortunately, continue during the dredging).

One local man had a pressing question that, it seems, that had not yet been considered: What happens if you fall in the canal?

“If people fall in the water,” Mugdan answered, “I’m afraid to say it will be difficult to get out.”

Related Stories

- Gowanus Historic District Shelved, Not Nixed

- What Exactly Is the Black Mayonnaise at the Bottom of the Gowanus Canal?

- Learn Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Gowanus Canal From Author Joseph Alexiou

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment