Brooklyn Navy Yard Aims to Boost New York's Creativity Cred [Photos]

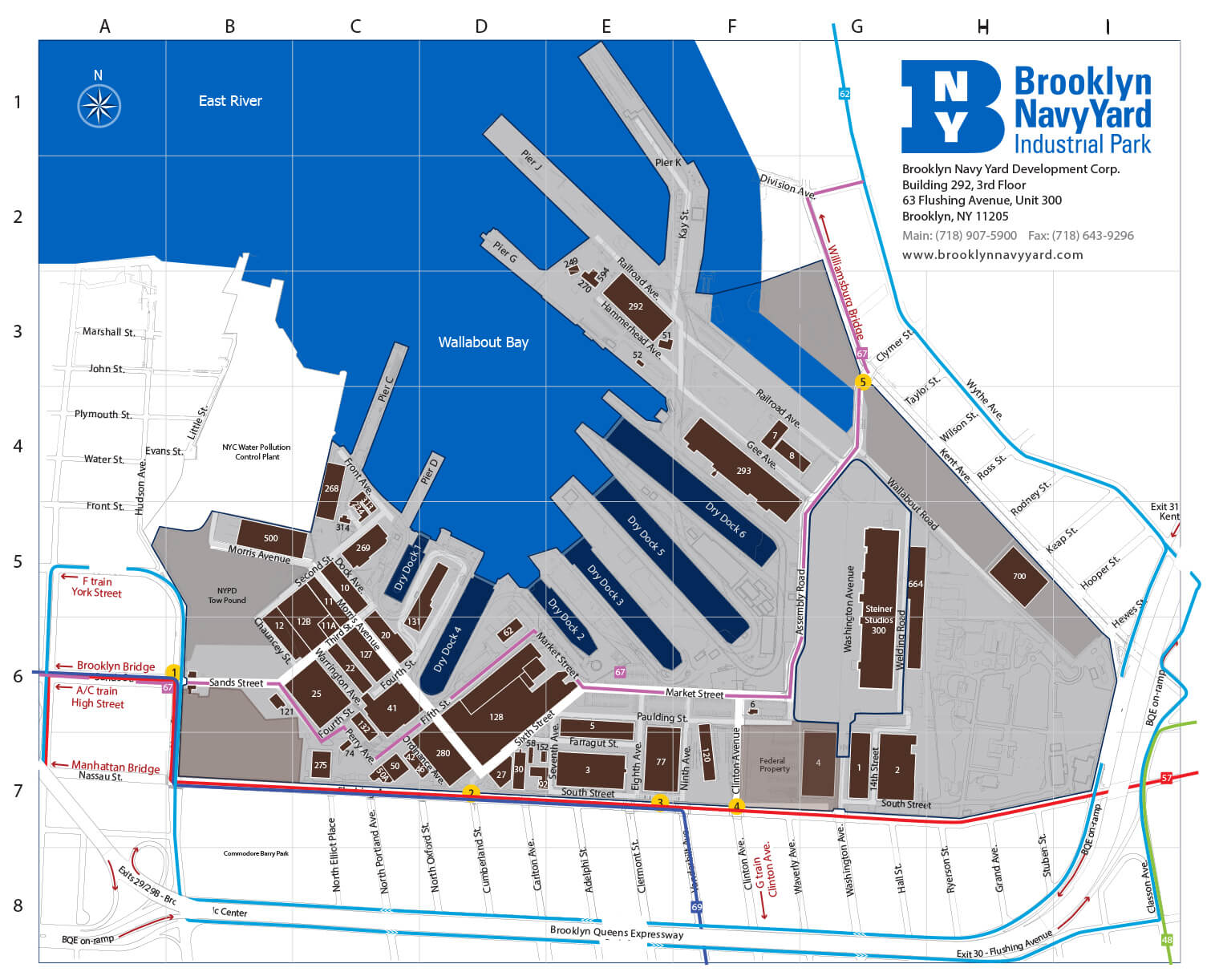

Only in New York could a 4-million-square-foot industrial park be considered a hidden gem. Yet despite its sprawling size and employment of thousands, the Brooklyn Navy Yard remains unknown to many borough residents. All of that is about to change.

A worker at Situ Studio, a custom design and fabrication firm

Only in New York could a 4-million-square-foot industrial park be considered a hidden gem. Yet despite its sprawling size and employment of thousands, the Brooklyn Navy Yard remains unknown to many borough residents.

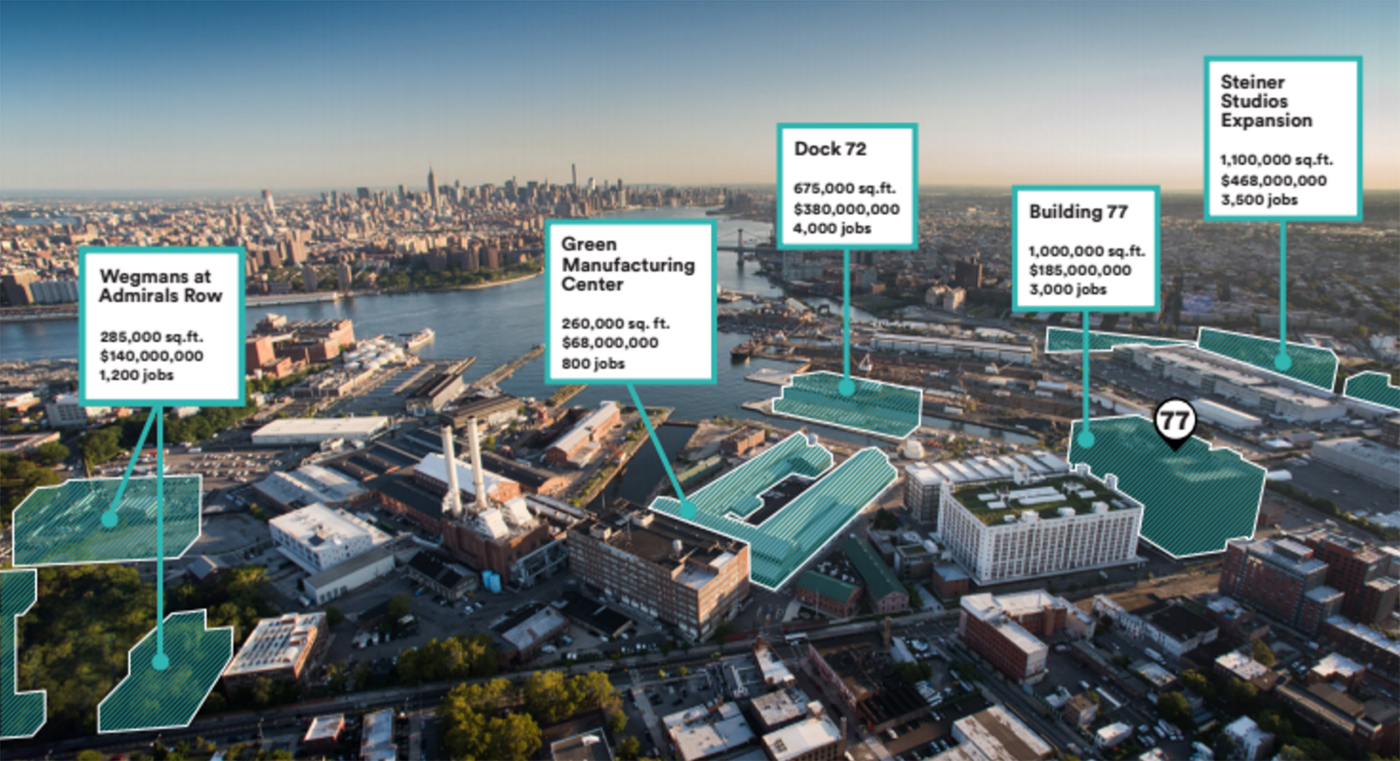

This will likely change in coming years as it doubles its employment to 16,000, completes its in-the-works food hall, launches a free two-loop shuttle service and creates its own app.

This expansion is a far cry from any of the incarnations the Navy Yard has taken on in its 215-year history. Created by John Adams in 1801 as a naval shipyard, it employed 70,000 during World War II, closed in 1966, and was little more than an NYPD tow pound for many years.

Still owned by the City of New York, the Yard is now run by a nonprofit tasked with promoting economic development. The nonprofit in charge is the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, whose president and CEO, David Ehrenberg, formerly handled real estate for the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC).

The Navy Yard aims to boost employment and creativity in Brooklyn by providing a space where private manufacturers in an array of creative fields can flourish. These aren’t the old line manufacturing businesses of yesteryear, but new innovative businesses — everything from movie making to recycling to design and custom fabrication. Arguably a success, the Yard is filled to capacity, so now the focus is on building out more space.

Only partly open to the public, the Yard is still easily eyed from Flushing Avenue, where a low fence and open entrances reveal goings-on along the border of the property.

This newest evolution is visible in the contrast of historic buildings to the modern projects they house, as well as the construction occurring throughout the industrial park. The neighborhood-sized manufacturing colony’s motto could well be “We Used to Launch Ships and Now We Launch Small Businesses,” as one tenant quipped on a recent visit, quoting a sign in the Yard.

As compared to other borough manufacturing parks, such as Industry City and the Brooklyn Army Terminal in Sunset Park, the Navy Yard is more oriented towards small businesses while sharing historical similarities (a military past, a period of abandonment). All host a variety of industrial makers, including food production.

With a cash infusion of as much as $670 million flooding the Navy Yard, a host of new developments are in the works, including a 74,000-square-foot Wegmans supermarket, the new WeWork building at Dock 72, the 1,000,000-square-foot Building 77, the expansion of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway and — perhaps — Mayor de Blasio’s ambitious plan for a streetcar which will connect the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts from Sunset Park to Astoria and, if approved, would wind along the East River, including the Navy Yard.

About 7,000 people currently work in the Navy Yard — it’s one of the biggest manufacturing centers in Brooklyn — at businesses ranging from Brooklyn Roasting Company to IceStone, ReFoundry, and Steiner Studios.

We met up with a handful of Navy Yard tenants to talk to them about what they do and why they do it in the Navy Yard.

The industrial park is treasured by its more than 300 industrial companies, our visit revealed — not just for the sense of history conveyed by the 300-acre yard’s landmarked buildings and its sweeping harbor views, but for the rare security and expansion potential it offers to manufacturing businesses.

“Coming into a space like this opens the imagination,” Situ Studio partner Wes Rozen said of his business, a design studio and fabrication shop that occupies a 10,000-square-foot production shop in the Yard. Besides the quantity of square footage, Rozen also appreciates that there’s “no threat of this being turned into luxury apartments. I feel we can grow for decades in this space.”

For businesses like Situ, which outgrew its Dumbo space, a Navy Yard lease means the ability to stay in New York while continuing to meet its full potential as a manufacturing business — an increasingly difficult proposition amidst ever-rising rents for commercial spaces. Indeed, there is a mutual sense among Yard businesses that the opportunities offered here are not just good for individual businesses, their employees and the Yard itself, but for the greater New York economy.

Rozen and other business leaders also discussed how the proximity of the Navy Yard allows them to collaborate and brainstorm with neighbors. A chance conversation at the food trucks can sometimes result in passing off parts of projects to other Yard shops. In addition, businesses feel work is plentiful enough that any competitiveness can be avoided, further sustaining the sense of community.

In the case of Ferra Designs, which specializes in architectural metal fabrication, the Navy Yard has been home for over eight years, the company moving to ever-larger buildings on the campus as business grew. It was founded in 1989 by Robert Ferraroni, who said the Yard’s embrace of manufacturing contrasts to Ferra’s previous locations, which have all been sold or turned into condos.

“The Yard wants to keep businesses here,” Ferrarnoi noted during a tour of his sprawling space, where he relocated less than a month ago from a smaller Yard structure.

Large industrial manufacturers are not the only tenants. Abby Lichtman, a Yard resident of four and a half years, is a textile print designer whose designs have been used by a diverse array of companies, from Target to Oscar de la Renta.

For Lichtman, the community, proximity to the water and security combine for a perfect workspace at the Yard.

“If it weren’t for the Navy Yard, my rent would be astronomical,” Lichtman remarked during a tour of her two-room studio. “I will never leave here.”

The Yard’s much-lauded affordability is instilled through its governance structure: by being owned by the city and run by a nonprofit, rents can be kept lower than in other for-profit commercial and industrial areas or mixed-use corridors where commercial tenants must compete with the tide of residential development.

A hub of not just revitalization but fresh development for the borough, the Navy Yard in many ways exemplifies the most positive of trends currently defining Brooklyn. There’s the constant development, the rebirth and growth after decades of stagnation, and the small businesses quickly growing to define their industries.

Yet, the Navy Yard contrasts to Brooklyn’s larger narrative in a few important ways: it remains relatively affordable, despite its success, it is loyal to its longtime businesses, and it encourages industry.

Right now, the Navy Yard is primarily an industrial park where a thriving community of artists and craftspeople, manufacturers and distributors, and other Brooklyn entrepreneurs ply their trade. Its visitor center, BLDG 92, stages exhibitions, events, and tours that showcase the past, present and future of this historic landmark.

In recent years, the Yard has lured the Manhattan-centric fashion crowd over the bridge for shows by some of the biggest names in fashion, including Alexander Wang and Dior. The latter showed in the Yard’s recently opened Duggal Greenhouse, a large and award-winning event space with stunning waterfront and bridge views.

With ambitious plans for expansion, however, the Yard plans to become a more public facing place while retaining its industrial past and present.

The cafeteria-style restaurant and shop coming to Building 77’s ground floor, set to open later this year, will be outfitted with its own public plaza and public entry to attract the general public in addition to workers on their lunch breaks. The food court will occupy a 60,000-square-foot ground floor space and will be designed by Marvel Architects, and will be anchored by iconic Lower East Side “appetizing” eatery Russ & Daughters.

The forthcoming Wegman’s grocery will also be accessible to the public. Even now, BLDG 92, which houses a museum about the Yard, is open to the public and can be reached via its own entrance. Tours of the Yard leave from BLDG 92 and take place every day.

So while for now the Yard remains a lesser known subset of Brooklyn’s generally shrinking industrial sector, a place where things are made but purchased elsewhere, within the next few years it hopes to become a destination for not just Brooklynites looking for secured manufacturing jobs, but for anyone who’s hungry or historically inclined.

[Photos by Hannah Frishberg]

Related Stories

Free Shuttle Will Make Brooklyn Navy Yard So Much Easier to Reach

Exciting Changes Coming to the Brooklyn Navy Yard

Three Huge Construction Projects Happening in the Brooklyn Navy Yard

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

[sc:daily-email-signup ]

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment