Williamsburg Air Quality Study Points to Pollution Hot Spots on Southside

A coalition of community groups conducted a two-year air quality study in Williamsburg that found levels of pollution higher than the state’s monitors, according to the environmentalists behind the effort.

Photo by Cate Corcoran

A coalition of community groups conducted a two-year air quality study in Williamsburg that found levels of pollution higher than the state’s monitors, according to the environmentalists behind the effort.

“With the state monitors, the first issue is that there are not enough … It’s not nearly enough to capture what’s actually going on,” said Jalisa Gilmore with the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, which spearheaded the study. “We were actually at the ground level.”

The Environmental Justice Alliance, which consists of 11 grassroots organizations from low-income neighborhoods, chose to measure the air quality in the southern half of Williamsburg and the south Bronx because of the locations’ historically underserved communities and traffic density.

“These are members who have long-standing air quality concerns,” said Gilmore about the choice to study the two locations. “This project was just our members’ response to concerns about air quality in their neighborhoods.”

Beginning two years ago, several member organizations of the Alliance, including the Williamsburg-based group El Puente, helped train paid volunteers to walk through the neighborhood with low-cost, portable air monitors in order to capture air quality measurements around the Williamsburg Bridge, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, and some of the neighborhood’s main avenues.

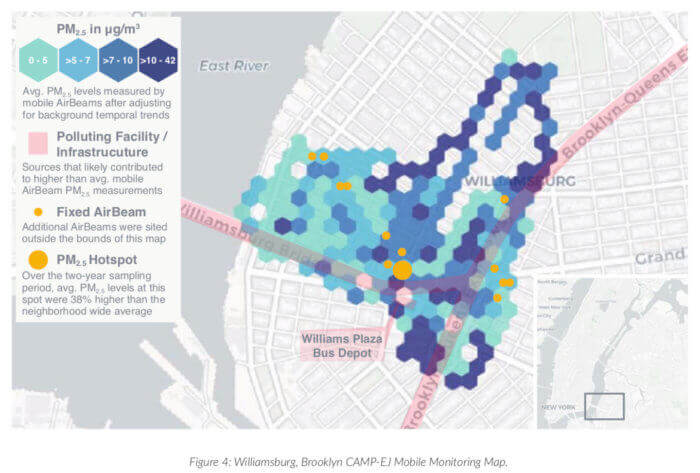

The volunteers measured the concentrations of PM2.5 — a very fine particle that can lodge itself deep into the lungs — in walks around neighborhood at different times of day, and ultimately compiled the findings into a map that the showed Williamsburg’s pollution hotspots.

The areas with the highest concentration of PM2.5, which comes from combustions of oil diesel fuel, or wood, are Bedford Avenue, Union Avenue, and the underpass of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, according to the map of the study’s findings.

In those areas, the levels of PM2.5 can reach from around 10 to 42 micrograms per cubic meter during rush hour between 7 and 8 am, and 3 and 4 pm, according to the findings. The pollutant levels rise again during the nighttime traffic rush at around 8 and 9 pm.

Experts claim that PM2.5 is potentially harmful to sensitive groups when at levels between 12 and 35 micrograms per cubic meter, and increasingly dangerous above that. But according to the executive director of HabitatMap and the co-author of NYC-EJA’s air quality report, exposure to the particle is dangerous at every level.

“There’s no safe level of exposure to PM2.5,” said Michael Heimbinder. “Every microgram that can be reduced in terms of exposure will improve health outcomes.”

High exposure to the pollutant can lead to health problems, like respiratory irritation and heart disease. The particle causes 2,000 premature deaths and 6,500 emergency department visits annually throughout the city, with high poverty neighborhoods experiencing a 28 percent higher mortality level than low poverty ones, according to two 2020 studies.

Heimbinder and Gilmore said that the Alliance’s daily findings were often higher than the closest state monitor reports because of their ability to track PM2.5 at the hyperlocal level. The state’s Department of Environmental Conservation operates 13 monitors across the five boroughs that track the air quality on an hourly basis, meaning the readings are less detailed.

“Those sites are not designed to measure personal exposures,” said Heimbinder, who explained that the state monitors serve to track the region’s air quality at a larger scale. “The monitors by the state are great for determining compliance with the Clean Air Act.”

To improve Williamsburg’s air quality, the Alliance urged the city and state to prioritize low-income neighborhoods like south Williamsburg and the south Bronx for green transportation initiatives, such as electric bike share projects, electric bus routes, electrical vehicle chargers, and increased cycling infrastructure.

The advocates also pushed for a green redesign of Continental Army Plaza by Roebling Street and the Williamsburg Bridge that would add environmentally friendly infrastructure and natural surfaces to temperatures and mitigate flooding.

Heimbinder said that in addition to bringing about policy change, he hopes the study can inspire other community groups to conduct their own surveys of their neighborhoods’ air quality.

“For me the thing that’s most important about the report is that it shows a community could undertake this work and do really great research,” he said. “And it’s really important if we’re going to make big decisions that we base them on solid information.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in Brooklyn Paper. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

- State Scolds EPA Expert for Voicing Concerns Over Pollution at Gowanus Affordable Housing Site

- Interactive Map Tracks North Brooklyn’s Industrial Past and Environmental Legacy

- Rezoning Proposed for Southern Brooklyn’s Flood-Prone Coastal Neighborhoods

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment