Walkabout: Plastered, Part Two

Read Part 1, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story. I am in the eternal process of renovating my apartment. It’s in an 1899 brick row house in Troy, and looks very similar to many of the later row houses you’d find in many parts of Brooklyn, with some regional architectural differences. Actually, some…

Read Part 1, Part 3 and Part 4 of this story.

I am in the eternal process of renovating my apartment. It’s in an 1899 brick row house in Troy, and looks very similar to many of the later row houses you’d find in many parts of Brooklyn, with some regional architectural differences. Actually, some of those differences are quite striking, and I plan on writing about it when I do some more research, but suffice it to say, where it counts, my Troy house is not all that different from my old Brooklyn house. Both were built in the same year, and both have many of the houses’ original plaster walls.

There are a couple of rooms in my apartment here that have had alterations over the years, and in the course of that, some of the walls have been replaced. I could tell you which walls are plaster and which are drywall in a hot minute. There is a feel to plaster that is totally different than the feel of drywall. Now, whoever did the replacement was good. There are no screws visible, or tape lines, and they put a good skim coat over the drywall. But it has that generic flatness, and it’s softer. Behind that skim coat, behind the thin sheet of drywall, is empty space and stud walls. Behind the thicker plaster walls, with three separate layers of plaster, is a wall of lath, and then the stud walls. Tap those walls. Solid. There is nothing that beats plaster.

Fortunately for me, the walls in my apartment are all good. A little bit of patching was needed to fill holes made for electrical and other repair work, and one spot where it looks like someone took their frustrations out on a wall. My apartment was college student housing a few years ago. Rensselaer Poly Tech is right up the hill, after all. “Quantum physics, argh!” Bam – foot through the wall. I can see it.

My ceilings, though – not so good. Some past roof leakage wrecked one ceiling; others have dropped ceilings that cover up years of deferred maintenance. And some have awful acoustic tiling pasted up there. Who knows what’s underneath? So I’m going to need to replace some of them. Guess what? The purist here is probably going to use drywall.

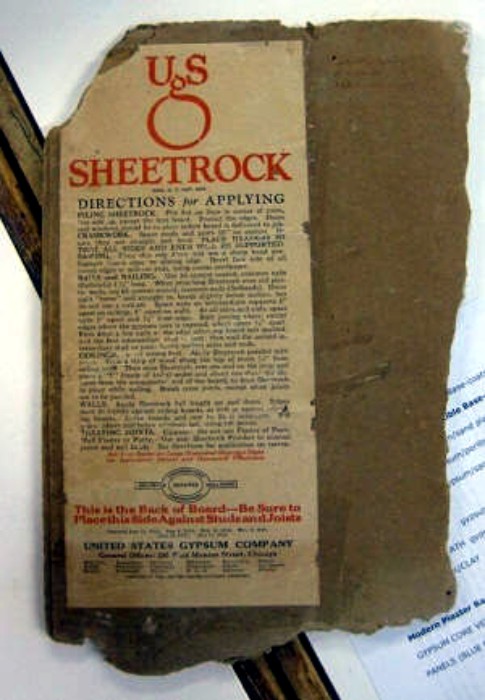

Both plaster and drywall are used in our period homes. But his was not always so. Last time, I talked about the history of plaster and its uses in building since antiquity. By the beginning of the 20th century, the United States Gypsum Company, one of the country’s largest plaster companies, started to sell a product they called “Sheetrock.” Like Kleenex, the brand name has become the commonly used product name.

Drywall, aka gypsum board, wallboard, “gyp” or Sheetrock is a layer of compressed gypsum sandwiched between two thick paper layers. Plastering is a wet art, dependent on the drying of the plaster to make a hard, smooth surface. Drywall is just that, it does not need (or want) water. The large Sheetrock panels could take the place of plaster, making building faster and cheaper. A piece of Sheetrock could be screwed to the wall in a matter of minutes. The same square footage of wall constructed by a plasterer could take all day, including the drying times between layers. You’d think it was a no brainer.

USGC, the gypsum people, launched sheetrock around 1916. It didn’t cause the buzz they thought it would, so they tweaked the product a bit, experimenting with the papers used to sandwich the gypsum, and tried again. It was now the late teens, early 1920s, the “Jazz Age.” Still no success. It actually took another twenty-five years or more for drywall to become a standard building material in American homes. So what was wrong with the wonder product, Sheetrock? Homeowners didn’t like it, that’s what.

They wanted time-honored plasterwork, done by skilled artisans who knew their craft, took their time, and did quality Old World work. Using Sheetrock was a sign of quickie, shoddy work. Builders were attracted by the product, but customers were not. They liked plaster. They liked that it was an art, a specialty, and they were willing to pay for the expense and time it took to get a fine plaster wall or ceiling. When builders and developers found that homebuyers were not impressed by Sheetrock, they didn’t use it. Sheetrock’s time had not yet come.

Unfortunately, World War II did. For the first time, there was a shortage of labor and materials, as the war effort took men away from all of the building trades to fight in the war. Master plasterers and carpenters got drafted too, and with a lack of skilled labor, the attention to domestic needs was put behind military needs. The American building industry had to go from time consuming skill to expediency. Drywall’s time had come. Labor intensive skills like plastering were replaced by speed and Sheetrock. It no longer mattered if you liked drywall or not, it was seen as patriotic to embrace new time and labor limitations, and go with what enabled the home front to pay more attention to war efforts. By the end of World War II, drywall had all but replaced plaster in new homes, factories and other buildings.

When the war was finally over, returning soldiers came home to massive housing shortages. This was the time of the Levittowns, the new suburbs across the country, and a national home building boom the likes of which had never been seen. All of the new developments; the ranch houses, the Cape Cods and split levels of the late 1940s and beyond used Sheetrock. It took a tenth of the time to put up a home with drywall than it did with plaster and lath. Less time, more profit, more homes. The ancient art of the master plasterer seemed to becoming about as useful as a fifth wheel. The American home building industry never looked back.

Over the years, drywall has evolved. It now comes in several thicknesses, and with different kinds of properties for different uses. Today’s standard sheets of drywall start in the factory with a mixture of gypsum plaster mixed with a fiber, usually paper. Different additives are then put into the mix; a foaming agent to speed up the chemical reaction, additives to retard mold and moisture, fiberglass as a fire retardant, some kind of wax to retard water and a starch or other emulsifiers to make it all stick together. The mixture is spread on sheets of heavy paper to the desired thickness, and another layer of paper is laid on top. The sheets are rolled to a drying chamber where gas ovens speed up the drying time and the moisture is baked out of the gypsum mix. There are, of course, other steps in there too; cutting, binding, etc.

Today, there are all kinds of drywall. We have the common variety drywall used in walls and ceilings. It comes in several thicknesses. Fire rated drywall, brand-named Perlite is made with extra fiber strands that enable it to hold up longer and resist flames. Greenboard is moisture resistant, for bathrooms or basements. The paper covering is moisture resistant; the gypsum core is the same as regular drywall. Impact resistant drywall was designed for places like schools or dormitories where it gets abused. Thicker fibers are used in the gypsum mix, as well as thicker paper on the outside.

Soundboard, or “quiet rock” is designed for apartment buildings, or anywhere where noise needs to be dampened. Viscoelastic polymers are added to the gypsum that convert noise energy into inaudible heat energy. Lead lined drywall is used in hospitals and rooms subject to radiation. A 1/16” layer of lead is placed between the gypsum core and the paper, preventing x-rays and radiation from penetrating it.

Flexible drywall is thin, ¼” drywall that can be moistened before use, and is typically used in covering curves and arches. Finally, there is blue board, which is typical drywall covered with a special paper that is treated to bond with veneer plaster, for a thicker, more plaster-like skim coat. Many of these drywall products are quite new, designed in response to new changes in building codes and homeowner preferences, as well as the limitations of standard drywall.

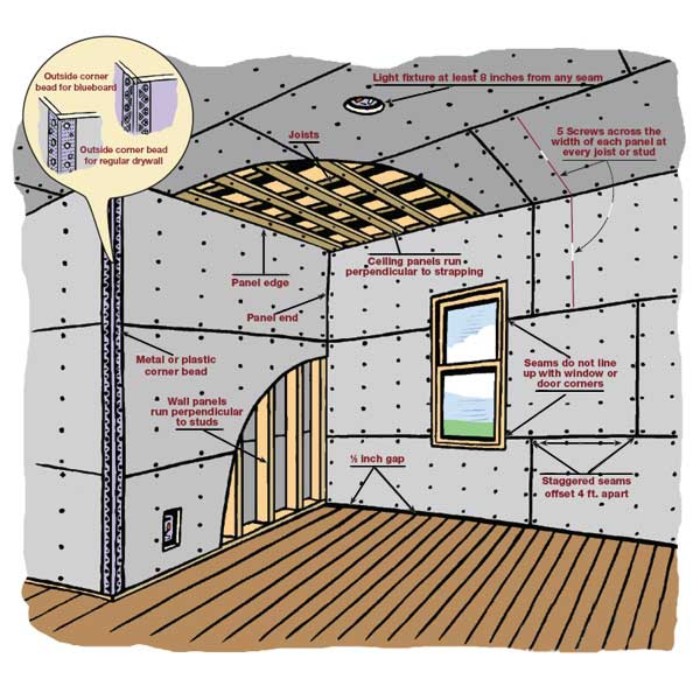

Traditional plaster involved troweling on three separate layers and formulas of plaster onto wooden lath. Each layer needed to be smoothed, and allowed to dry before the next layer was applied. The top coat, especially, required the talents of a master plasterer. Plaster took days to dry, and needed to cure before paint or wallpaper was applied. With drywall, a crew could sheetrock a small house in the time it took to plaster a room. All you needed was a framed stud wall, a drill, some screws, a drywall knife and a helper, whether human or mechanical, to hold the sheet in place while you got the anchor screws in.

After the drywall is screwed to the framing, the seams need to be covered with drywall tape and a layer of joint compound, or “mud.” The compound, whether mixed from powder or pre-mixed, is made up of limestone, emulsifiers, various polymers, and water. It covers the taped seams, as well as the screw holes, creating a smooth surface that is sanded before painting or wallpapering. Often, a skim coat is applied at this point, covering the entire paper surface of the sheetrock to make it less flat, and more like a traditional plaster wall.

The popularity of home show networks like HGTV and DIY, and other network and cable shows have taken the mystery out of the home building industry. You can watch shows that depict a crew of hip and attractive people, ‘rocking and mudding an entire room in no time, and decorating it, too. Shows like “Extreme Home Makeover” have entire houses built and decorated to the max, in a week. Everything now is not only quick, quick, but unless you have four thumbs, you should be able to do it yourself, too. Whatever happened to the master plasterer? Are there any left, or is it a dying art?

Next time we’ll look at the old house revival movement, in terms of plaster and Sheetrock, and look at old house plaster repair. Has DIY done us in? Can plaster and Sheetrock co-exist?

(Photograph: Early drywall, aka “Sheetrock.” welkandsonsdrywall.com)

thanks for listing some of the different drywalls.

I wanted to post this last week in the thread with the pic of the guy in the bathtub with greenboard.

“Greenboard is moisture resistant, for bathrooms or basements. The paper covering is moisture resistant; the gypsum core is the same as regular drywall.”

Greenboard is moisture resistant NOT waterproof and shouldn’t be used around the shower and bathtub walls. Over time, cracks will develop in the grout and moisture will make its way to the greenboard deteriorating it.

Cement board should be used on shower/tub walls.

Many homeowners don’t know the difference and many times rely on the contractor for info. Sadly many contractors like using greenboard because it’s easier to work with than cement board.

But as a homeowner renovating a bathroom, you’re investing in your property and you should use a superior product that will hold up over time.

Installing greenboard in shower surrounds was a industry standard that probably started shortly after the advent of the residential inter moisture resistant board. Unfortunately, it did not become a bad practice till tiles and grout started to pop out which was years or even a decade or so later. I’ve seen architectural drawings in the mid-eighties

“You’re right.”

did a pig just fly by?