Walkabout: Calvert Vaux, Architect, Part 4

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of this story. Prospect Park was not even half completed when it opened to the public in 1867. It was a huge success, made even larger over the next six years, as work continued. Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted created one of the greatest urban parks in…

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of this story.

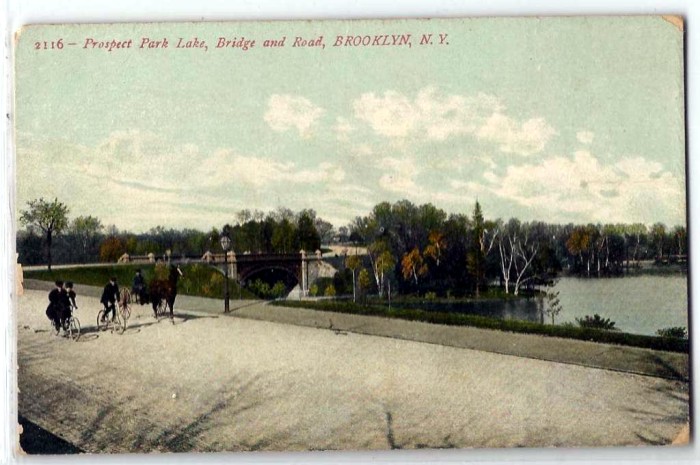

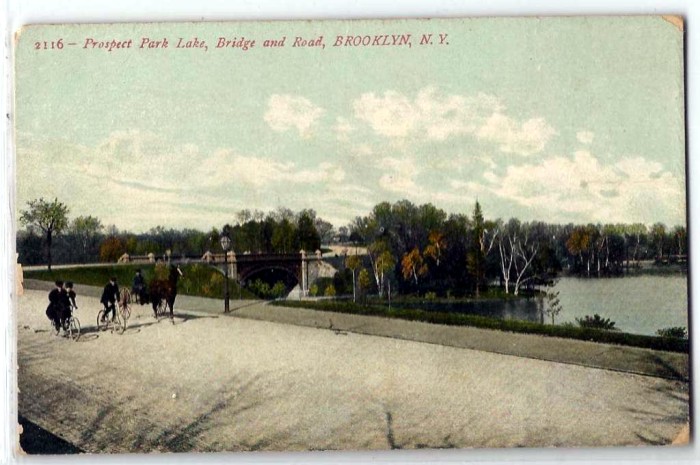

Prospect Park was not even half completed when it opened to the public in 1867. It was a huge success, made even larger over the next six years, as work continued. Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted created one of the greatest urban parks in the world, combining nature and architecture seamlessly into the center of Brooklyn.

They had already become well known because of Central Park, but Prospect Park enabled them to create something even bigger and better, and it was indeed good.

But they didn’t rest there. Olmsted and Vaux, who had become business partners at the beginning of their Prospect Park project, were in high demand, both in Brooklyn, and elsewhere. While the workmen were still creating Prospect Park, they started work on the great boulevards that sprang from the park’s entrances.

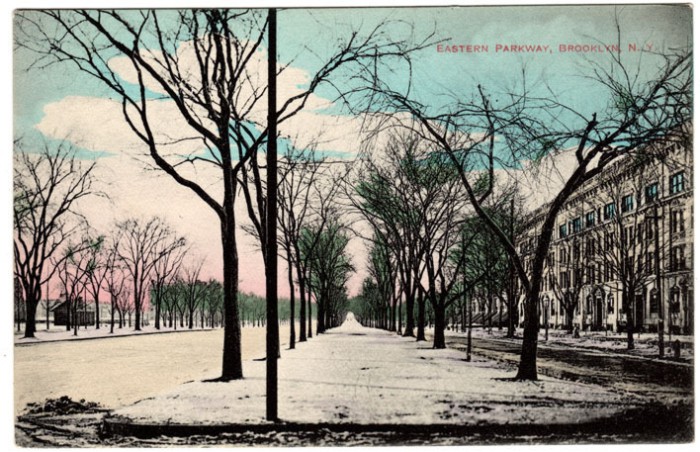

These roads would not just get one from along the route to the park; they would ring Brooklyn with a necklace of interconnected roadways and parks, bringing the country into the city. The first strings of that necklace were Eastern Parkway and Ocean Parkway.

Olmsted and Vaux presented the city fathers with the plans for both parkways as plans for Prospect Park were proceeding. They based their designs on the great boulevards of Paris and Berlin, where wide center roads for traffic were flanked on both sides by bands of trees and plantings, sidewalks for strolling and bridal paths.

Service roads would also be built on both sides, and they envisioned stately mansions and homes lining the routes.

Eastern Parkway would travel past the Mount Prospect Reservoir, linking it to the nearby park, and then travel eastward to the edge of Brooklyn. Ocean Parkway would begin at the other end of the park and lead out to the sea.

The city fathers loved it, approved the plans, and began buying the land in 1868. Eastern Parkway was first, completed between 1870 and 1874. Construction of Ocean Parkway began that same year, and it was completed in 1880.

Both roads were very popular, and as predicted, fine homes were built along both parkways. Both became popular promenade spots, where people strolled, sat at benches and tables to rest and talk, and took in the beautiful trees, flowers and shrubs that lined the way.

The bridal paths were also very popular. On Ocean Parkway, they may have been too popular, as impromptu horse racing began to become a problem, as racing aficionados, heading down to the tracks at Coney Island, got in a few races of their own beforehand.

As bicycle riding gained popularity in the 1890s, Ocean Parkway had the first bicycle path in the United States. The pedestrian walkway was split to include a bicycle path. A ride down to the shore in summer was as popular then as it is now.

Both boulevards were highly successful, and another feather in Olmsted and Vaux’s hat. Today, both parkways are landmarked and on the National Register of Historic Places.

Around this same time, also in 1867, they were commissioned to fix Washington Park. It was Brooklyn’s first city park, but needed work.

Olmsted and Vaux conceived of putting the crypt containing the remains of the Revolutionary War prison ship dead in a memorial in the park, with a small monument.

That monument would be elaborated on 30 years later by Stanford White. They also landscaped the park, laying pathways and plantings, taking advantage of the hilly terrain.

Morningside Park in Manhattan followed. Olmsted and Vaux had literally transformed the park landscape of the two greatest cities in America. They would go on to create a beautiful park in Buffalo, one very similar to Prospect Park, and a treasure to that city’s people.

That was followed by a park for New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the grounds for two hospitals for the insane, one in Buffalo, the other in Poughkeepsie.

In 1872 Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted dissolved their partnership. They were moving in different directions, and the much more outgoing and personable Olmsted was being asked to do a lot of park projects on his own.

Vaux had other interests as well, including getting back to designing buildings. The two remained on good terms, and would team up again, one last time in 1889, to design Downing Park, in Newburgh, a tribute to Andrew Jackson Downing, the great American landscape architect who had been such a mentor to Vaux, and who had introduced him to Olmsted those many years before.

That tale, as well as the early years of partnership and projects can be found in Part One, Part Two and Part Three of this story.

Calvert Vaux continued his interests in architecture. Both he and Olmsted had strong views on social issues, and Vaux was interested in designing housing for the poor, as well as multiple unit dwellings for all classes of people.

He had actually written a paper that he presented in 1857, where he advocated for apartment buildings, which he called “French flats,” twelve years before Richard Morris Hunt built the Stuyvesant Apartments in Manhattan, regarded as New York’s first higher end apartment building. He gets no credit for that.

But he does get credit for his other architectural undertakings. In the 1880s, he designed a building for the poor for the Improved Dwellings Association. He also designed twelve projects for the Children’s Aid Society.

The same year he broke up with Olmsted, 1872, he partnered with engineer George Kent Radford to design a pavilion for the 1876 Philadelphia Exhibition. It was a brilliant piece of architecture and engineering, and would have been one of his finest works, but it was never built, as the fair owners balked at the cost.

Still partnered with Radford, Vaux went back to charitable work, designing the 14th Ward Industrial School on Mott Street, (1889) and the Elizabeth Home for Girls (1892) on East 12th Street. Today, both are still standing, and are landmarked.

His more well-known architectural projects are a town house for Samuel Tilden in Gramercy Park, the Jefferson Market Courthouse in Greenwich Village, and the original Gothic buildings for both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Natural History.

Both of the museum buildings are still there, although totally surrounded by later additions. By this time architect Samuel Parsons to the firm. His old associate, Jacob Wray Mold, who had collaborated with him in the bridges and buildings of Central Park, partnered with him again to help design the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By the 1890s, Calvert Vaux was the official landscape architect for the New York City Department of Parks. His latest project was a park for the Bronx. In 1895, he was seventy years old, and was getting tired, although that didn’t stop him from working himself to exhaustion.

After finishing the plans for the Bronx project, he took a month off, and went with his daughter, Marian, to a resort hotel for some rest. He was under a doctor’s care at the time.

He was fond of spending time with his four children; his two daughters, and two sons. One of his sons, Downing Vaux, was named for his mentor. The other, C. Bower Vaux, owned a home in Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea, and Vaux enjoyed staying there, near the ocean.

On November 20st, 1895, Calvert Vaux was staying with his son, and went for a walk on the pier. He never came home. Searchers later found a body the next day, wedged in some rocks near the shore.

With some difficulty they were able to bring it to shore, and C. Bower Vaux was called in to make the identification. It was Calvert Vaux. The Brooklyn Eagle stated that he had committed suicide, citing his medical care for nervous prostration and exhaustion as the reason for the deed, but there was no evidence of that whatsoever.

The family emphatically stated otherwise, telling the New York Times that their father must have slipped and fallen into the ocean. He was a frequent visitor to that pier, but the day had been cold and damp, and Vaux had slipped.

That explanation has endured. Those who knew of Vaux’s contributions to the city and to the beautification of his environment mourned his loss. Today, a park in Bensonhurst is named after Calvert Vaux.

Of course, the Vaux legacy is great. We enjoy it every time we go to his parks, walk along Eastern and Ocean Parkways, or visit one of his buildings.

His work in Newburgh remains, and his name, although it does not trip from the tongue as easily as Frederick Law Olmsted’s, is especially synonymous with the parks he created. Millions enjoy those parks every day, and they are destinations that shouldn’t be missed. What a fine legacy for anyone to have.

This was a great series, MM. Thanks.