Walkabout: A Partnership in Brick and Mortar, Part 2

Read Part 1 of this story. Developer Louis F. Seitz was only twenty-five years old, when in the late 1880s, he had hired another twenty-five year old, an up and coming architect named Montrose W. Morris to design what both hoped to be the first in a series of luxury apartment buildings in the better…

Read Part 1 of this story.

Developer Louis F. Seitz was only twenty-five years old, when in the late 1880s, he had hired another twenty-five year old, an up and coming architect named Montrose W. Morris to design what both hoped to be the first in a series of luxury apartment buildings in the better neighborhoods of Brooklyn. No one in Brooklyn had done this before – built a five story luxury building where well-to-do tenants could live in apartments as luxurious and stately as large as any average row house, but all on one level.

This was going to have to be spectacular, because here in America, the idea of living in multi-unit buildings had a bad reputation. Upper income folk in this country went over to Europe like a cultural pilgrimage, but the one cultural habit Parisians, Londoners, Berliners , Romans and most European city dwellers shared, but Americans didn’t, was a love for living in apartments. For independent Americans, a proper home meant one’s own house, not living on top of, or down the hall from strangers. That was for the poor in tenements, not them.

But developers and city planners knew that land was finite, and people were still coming, and the demand was overwhelming the supply. Plus there were those who, for whatever reasons, did not want to live in a house, it just didn’t suit their lifestyle or situation. The first apartment buildings for the wealthy in Manhattan were residential hotels, and the famous Dakota, finished in 1884, was the first full-scale luxury apartment building in New York City. Louis Seitz wanted his building to be Brooklyn’s Dakota, and in Montrose Morris, he had found the man who could deliver his vision.

Part One of our story tells of the meeting of Morris and Seitz. Little did either know that when Morris opened his new home up as a show house, and show-off house, that the man who gave him his business card, and said, “Come see me, I have a project for you,” would become a good friend, and fast business partner in projects that would last until Morris’ rather early death at the age of 54.

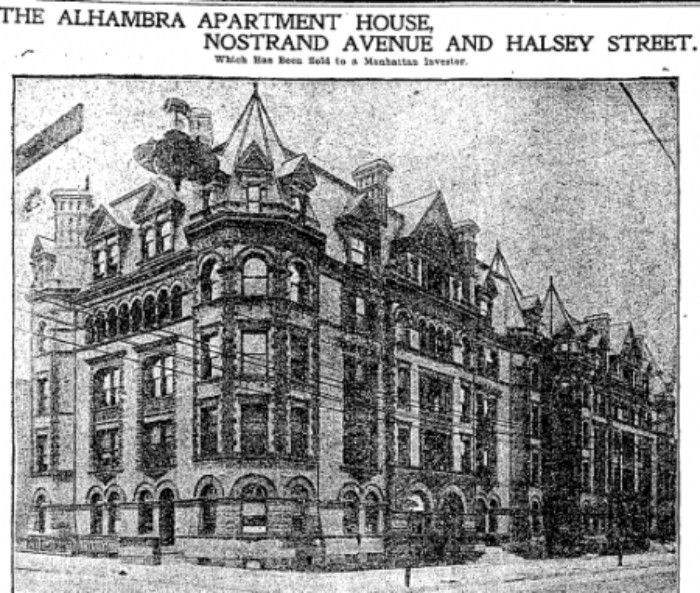

Morris had designed flats buildings before, as had many others. They were flats buildings for middle class tenants, far better than tenements, but not luxury accommodations. In 1889, M.W. Morris filed for a permit from the Department of Buildings for his Alhambra Marble House, the building’s first name. This Romanesque Revival building was of course, named for the famous Moorish Spanish palace, even though his design had very little to do with either Spain or Moorish architecture. It was branding, pure and simple, an exotic name chosen to make a certain impression.

No sooner had the foundation been dug out, than the problems began. The crew of over 40 stone masons who were supposed to be laying the stone foundation went on strike, because the contractor had hired non-union brick carriers. When the contractor refused to fire the brick carriers, the other unions represented on the project staged a sympathetic walkout, and would not allow any new materials to be delivered on the site.

Although some today in this anti-union climate would see this as typical union obfuscation, the truth is that in the late 1800s, unions were necessary to worker’s rights, as construction men were generally forced to work long hours, in what would now be very unsafe conditions, for little money, and even fewer rights. This was the age of our history when belonging to a union could be a death sentence. Many of the robber barons of the day had been known to pay people to rough up union striking workers, and even kill union organizers. But in this case, the strike was quickly settled, the unions were placated, and work continued.

The Brooklyn Eagle gave a fulsome description of the Alhambra, down to the pipes in the bathrooms. The building had all the bells and whistles of the finest row house, with the conveniences of a fine hotel. The Alhambra takes up the entire block of Nostrand, between Macon and Halsey Street, and is 200 feet long and 70 feet wide. It is five stories tall, and originally had six apartments on each floor, for a total of 25 in total. The ground floor had a large reception area leading to a lobby with a huge fireplace, and a wide curved set of stairs leading to the upper floors. There were doors leading outside, where there was a lawn with a fountain, croquet courts, and benches, all of which could be seen from the side streets.

The façade was unlike anything anyone had seen, a huge brick building with towers, dormers, loggias and arcades on the upper floors that gave those tenants an outdoor porch. There was rich terra cotta ornament everywhere, and so much to look at and admire, the building soon became a popular postcard.

The apartments were huge, with eight or nine rooms, all with windows opening to either the front or back of the building. Each apartment had a reception hall, library, dining room, parlor, bathroom, small butler’s pantry-like kitchen, and three or four bedrooms. The parlors were all in the tower rooms, as Morris had designed the building with six towers, four on the ends, and two in the middle. The main design feature, which would become a Morris signature, was a series of pocket doors between the reception hall, library, dining room and parlor, which enabled the tenant to open up the rooms for one large entertaining space. Of course, each room was decked out in appropriately fine woodwork, fireplaces, tile, and the latest in bathroom accoutrements.

When the building opened in 1890, it was a hit, and was rented out quickly. Louis Seitz took one of the apartments himself. The tenants were stock brokers, bankers, lawyers, and other well-to-do people, including the principal of the Girls High School, just across the street. Seitz and Morris were hailed as visionaries, and were soon hard at work looking for more property to develop, specifically for large apartment buildings. They built the Arlington, on the edge of Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights, this one scaled down to a more middle class audience, but with many of the same detailing as the Alhambra.

Montrose had his own thing going, as well, developing much of Hancock Street, between Marcy and Tompkins, the block he lived on. He designed a mansion for John Kelly, who had made a fortune in the water meter business, and he developed, some with Seitz’ help, three groups of houses on the block, plus the corner house next door to his own, which was in most ways a twin to his house, both inside and out.

By 1892, the pair was over in the nearby Grant Square area. There Morris and Seitz built the Imperial Apartments, and next door, the Bedfordshire, a smaller, but equally luxurious building. The Imperial was Morris in his new medium, light golden toned bricks with limestone and white terra-cotta trim. While enormous arches framed multi-storied windows, this building was encrusted with classical detailing, and just as much a masterpiece as the Alhambra. Next door was the Bedfordshire, a smaller building with its own arched charm. Both buildings had the same layout as the Alhambra, and attracted the same sorts of tenants. By this time, the Grant Square area was blossoming into a chic cultural area, with the prestigious Union League club a block away, and the 23rd Regiment Armory down the block, home to Brooklyn’s famed National Guard regiment, with some of the city’s wealthiest sons among the officers. Louis Seitz, always ready for the next, moved from the Alhambra to the Imperial.

More apartment buildings would follow, and by this time Montrose Morris was well established as one of Brooklyn’s finest architects, a man who designed the best for the best. He had designed mansions for the Arbuckle, Hulbert, Luckenbach, and Feltman families, and had built his signature groups of houses in Clinton Hill and the St. Marks District. He had also designed large additions to the Hotel St. George in the Heights.

He followed up the Imperial with a smaller version called the Renaissance, which is only a block away from the Alhambra, on Nostrand Avenue. Like the Imperial, it looked like a Loire Valley chateau on classical steroids. He designed two other French style castles, almost twins as well, on Decatur Street and Clinton Avenue. By now, these buildings were not luxury, per se, but upper middle class. This was the fastest growing market, and Louis Seitz was again, right on the money. More such buildings would follow, including a scaled down version of the Alhambra, called the Montrose, on Schermerhorn Street, downtown.

In 1894, Louis Seitz decided to throw Montrose a party. It was at the Union League Club, in Grant Square, not all that far from their homes. Fifty of their closest friends, colleagues and clients were invited, (men only), and they hailed and feted the great architect. A string quartet played in the background while speeches were given, and Montrose received a tall Viennese vase on an onyx base from the men gathered. He made a gracious acceptance speech, and the affair made the papers. In reading the names of the men attending, it’s interesting to note that no other architects were present. Montrose, in his long career, never associated himself with other architects. He belonged to no organizations, and his name only appears with other firms when he was competing against them for commissions.

As the 20th century progressed, Montrose continued his impressive career. More mansions in Park Slope and the St. Marks district followed. He and Seitz collaborated on a small hotel called the Marquise, on Herkimer Street in Bedford, and later, their last big collaboration, the Chatelaine Hotel, on Grant Square. This was a very large residential and transient hotel, designed to house a well to do clientele of businessmen on the go, and residents from the upper classes. It was modeled on similar successful hotels in Manhattan and Brooklyn Heights. With the LIRR train right at Nostrand, the hotel drew a lot of business traffic. It was an elegant hotel, with classical interior details, and a large columned dining room and lobby. The building was finished in 1912, and Morris did an addition in 1914.

It would be one of his last Brooklyn projects. On April 14, 1916, Montrose Morris died at the age of 54. He left his wife and sons with a great legacy and a lot of debt. He would have been rather upset to know that his obituaries were much smaller than they probably should have been, and he wasn’t even mentioned in the New York Times. His colleagues, whom he had ignored when he was alive, ignored him when he died. Only Louis Seitz missed his friend of many years.

The Alhambra, the Imperial, even the Chatelaine had all been sold years ago, and by the 1940s Louis Seitz was an old man. In 1930, he sold The Chatelaine Hotel, one of his favorite buildings, to the Swedish Hospital, which had transformed the elegant hotel into a large hospital facility, much needed in the community. Gone were the marble columns and the grand dining room. Perhaps, then, it was fitting that he chose Swedish Hospital as the place he would die, succumbing to illness at the ripe old age of 85. He had survived his wife by five years, and Montrose by thirty. He and his wife are buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Montrose and his wife are buried at Green-Wood Cemetery. We are fortunate that most of the buildings this duo built together still stand a legacy of business savvy and a firm friendship.

(Photo of former Chatelaine Hotel, Bedford Avenue at Dean Street, Crown Heights North)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment