The Brooklyn Children's Library and How It Grew Thanks to Founder Clara Whitehall Hunt

Generations of Brooklyn children were able to take visual delight in picture books, escape into fairy tales and learn more about the world beyond the borough thanks to the efforts of one woman.

Photo by Susan De Vries

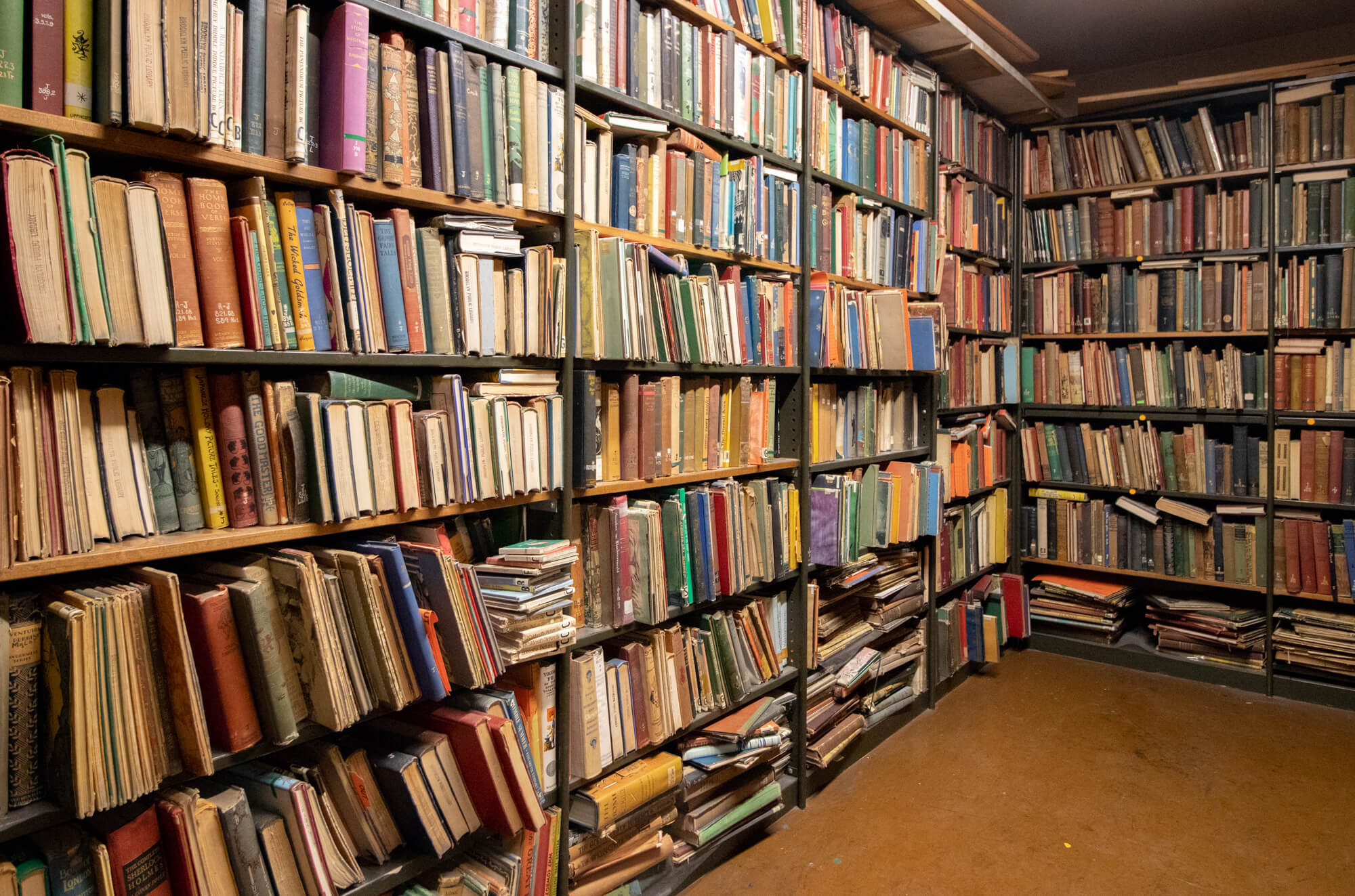

In an off-limits section of Brooklyn’s Central Library there’s a room lined with treasure. Crack open the doors and what lies inside is perhaps a bit unexpected — not a hidden stash of gold, but the aging spines of juvenile literature from the 18th through the mid 20th centuries.

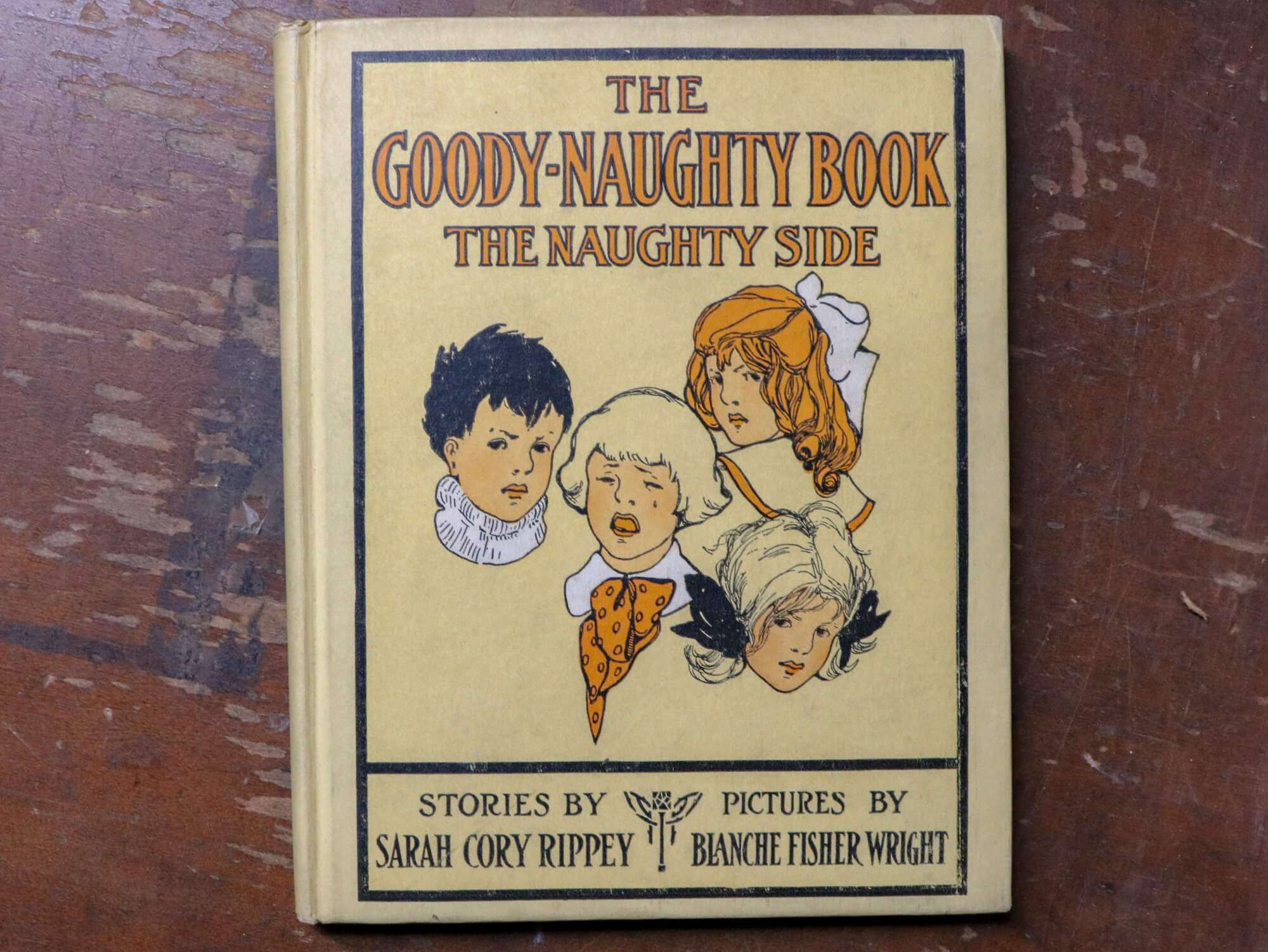

Roughly 13,000 books line the floor-to-ceiling shelves, their once bright covers a bit faded but still intriguing, with whimsical illustrations and amusing titles still visible on their spines.

The collection is just one of the legacies left behind by a woman who should be well-known by Brooklynites, but probably isn’t.

Generations of Brooklyn children were able to take visual delight in picture books, escape into fairy tales and learn more about the world beyond the borough thanks to the efforts of one woman who spent 36 years working in the Brooklyn Public Library system focusing on needs of young readers.

Fresh from several years as the head of the Children’s Department in Newark, N.J., Clara Whitehall Hunt arrived in Brooklyn in 1903 to tackle the job of Superintendent of the Children’s Department at Brooklyn Public Library.

She joined the library staff at an exciting time: Brooklyn’s many independent libraries had only recently been consolidated into a borough-wide system, and funding from Andrew Carnegie in 1901 meant the construction of multiple new branches.

Hunt was a former teacher and 1898 graduate of New York State Library School with a particular passion for nurturing young minds through literature. During her tenure in Brooklyn, she was able to bring children’s reading rooms to more than 30 branches in the borough and open one library branch dedicated solely to children.

To create the Children’s Library in Brownsville, Hunt worked with architect William B. Tubby to create a library that would stoke the imagination of young readers and provide them a space free from the constraints of older readers. Tubby designed a fanciful, castle-like structure with decorative references to children’s literary characters.

The library at 581 Stone Avenue (now Mother Gaston Boulevard) opened in 1914 with more than 8,000 volumes aimed at young readers. In 1929, the library expanded its programming to include teenagers, and after World War II the name was changed to the Stone Avenue Branch when the library expanded beyond its initial focus on children’s literature.

When determining what those original 8,000 volumes in the library would include, Hunt had fairly strong opinions. In her 1915 book “What Shall We Read to the Children?” she argued that “a healthy child is a live interrogation point” and that libraries where a young child “tumbles about” had a “tremendous influence upon the interests and tastes of that child to the end of his life.”

She also bemoaned the fact that “young mothers today are so appallingly wise!” She pondered that perhaps while parents are focusing on the latest knowledge about “the care and feeding of children’s bodies” they should also give equal attention to what their children are reading.

To inform parents and other libraries, she created lists of recommended books for boys and girls that were distributed nationally. She also focused on ensuring the Brooklyn Public Library was spending money to acquire books that met her standards and hiring librarians who were trained specifically to work with children.

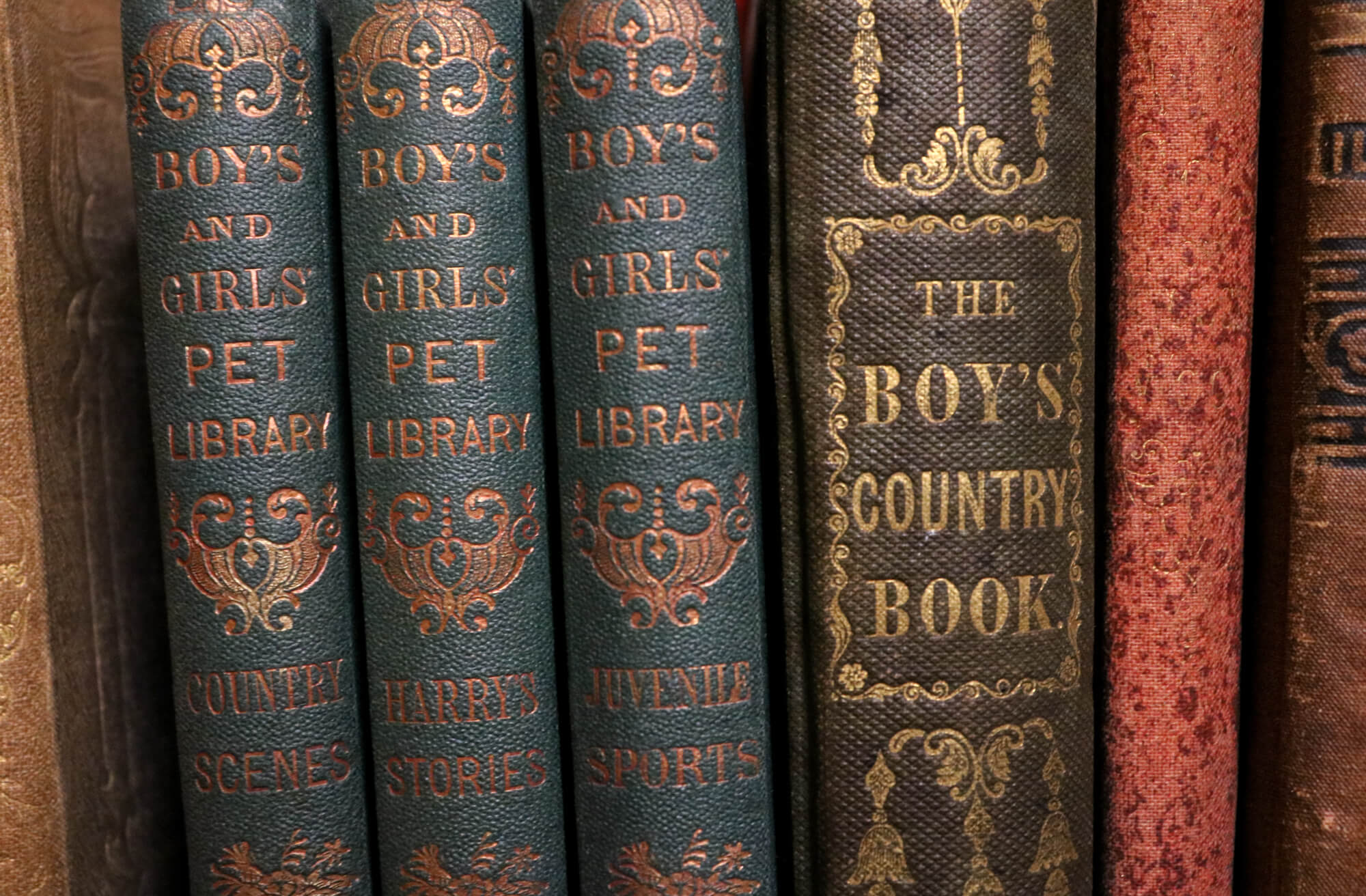

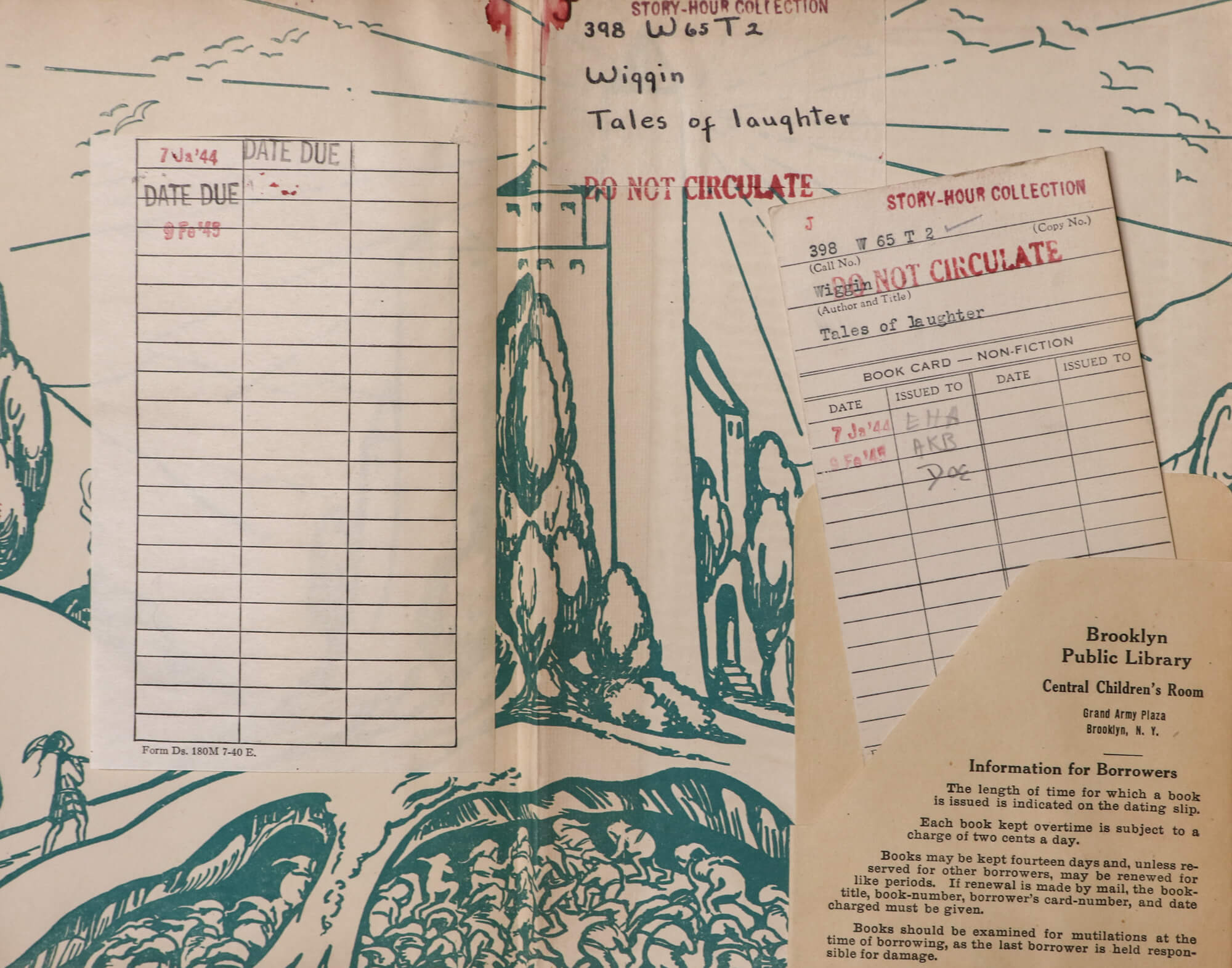

In 1925, Hunt spearheaded the acquisition of what she described in the Brooklyn Public Library Annual Report for that year as a “valuable and delightful collection” of “old-time books for children.”

That initial purchase included 445 books, the core of what would become known as the Old Juvenile Collection. The treasure trove of books included 18th and 19th century volumes, with the oldest dating to 1741. Those books, still in the collection, include textbooks, hymn books and moral tales.

Some are works by authors perhaps recognizable to contemporary readers, like Louisa May Alcott’s tales of the March sisters and Horatio Alger’s inspiring sagas of impoverished orphans rising to success. Others are from authors like Sarah Knowles Bolton and Charlotte Mary Young whose books were well known when published but haven’t stood the test of time.

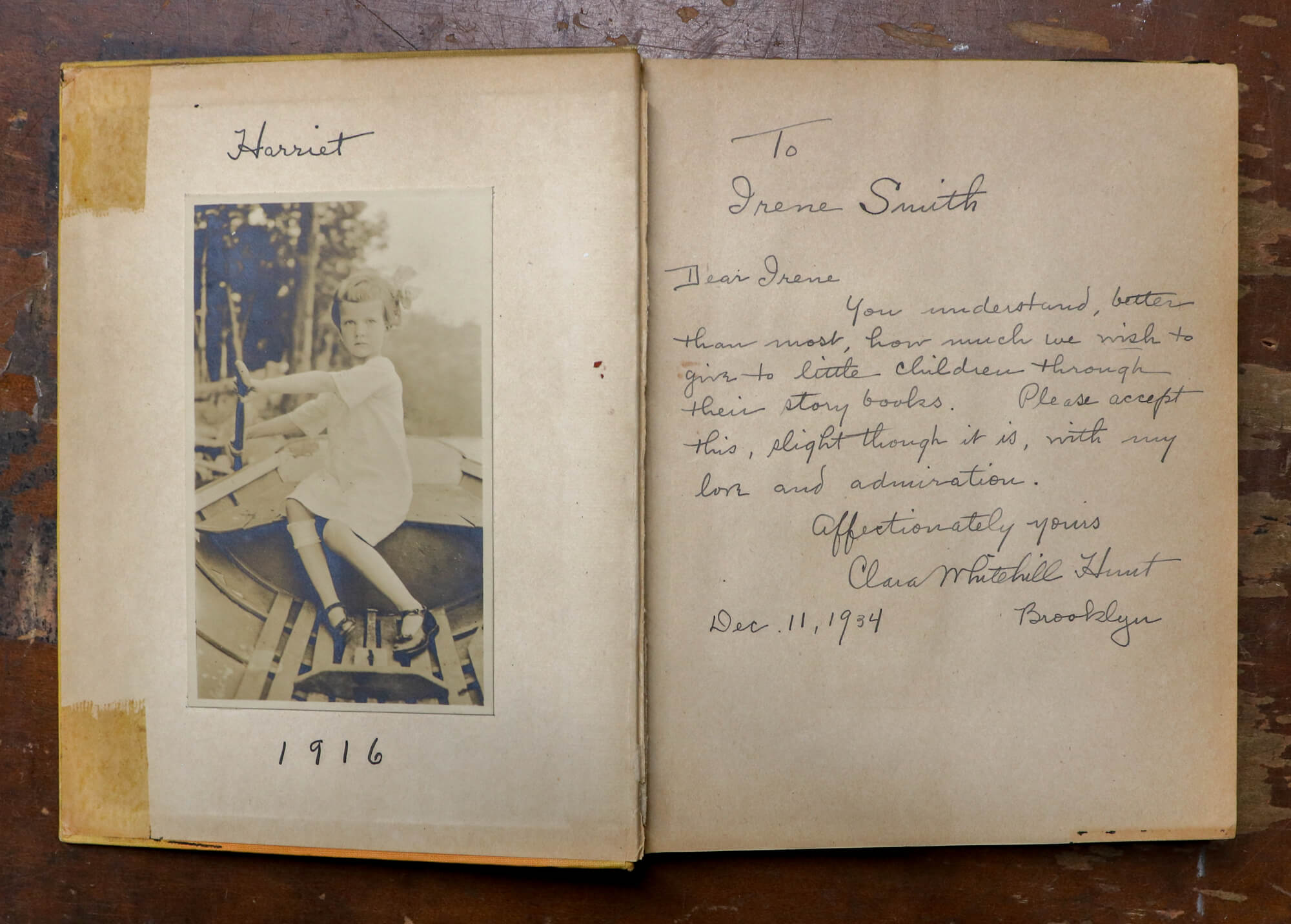

The collection grew as books were added as either gifts or purchases, some of those arranged by Hunt. Hunt, who put her literature theories to the test by producing children’s literature of her own, is also represented in the collection.

“About Harriet,” published in 1916 with illustrations by Maginel Wright Enright, follows a young girl through her week at home in the “big city.” The book includes a bit of meta messaging as the young character at the center of the story goes to the library and a kindly librarian helps her find the right book to engage her imagination.

Hunt retired from Brooklyn Public Library at the end of 1939, but the collection of juvenile literature continued to grow. Hunt died in the 1950s and a memorial fund was established in her name so that more books could be purchased. By 1963, there were more than 3,000 volumes in the collection and now the Old Juvenile Collection holds more than 7,000 books.

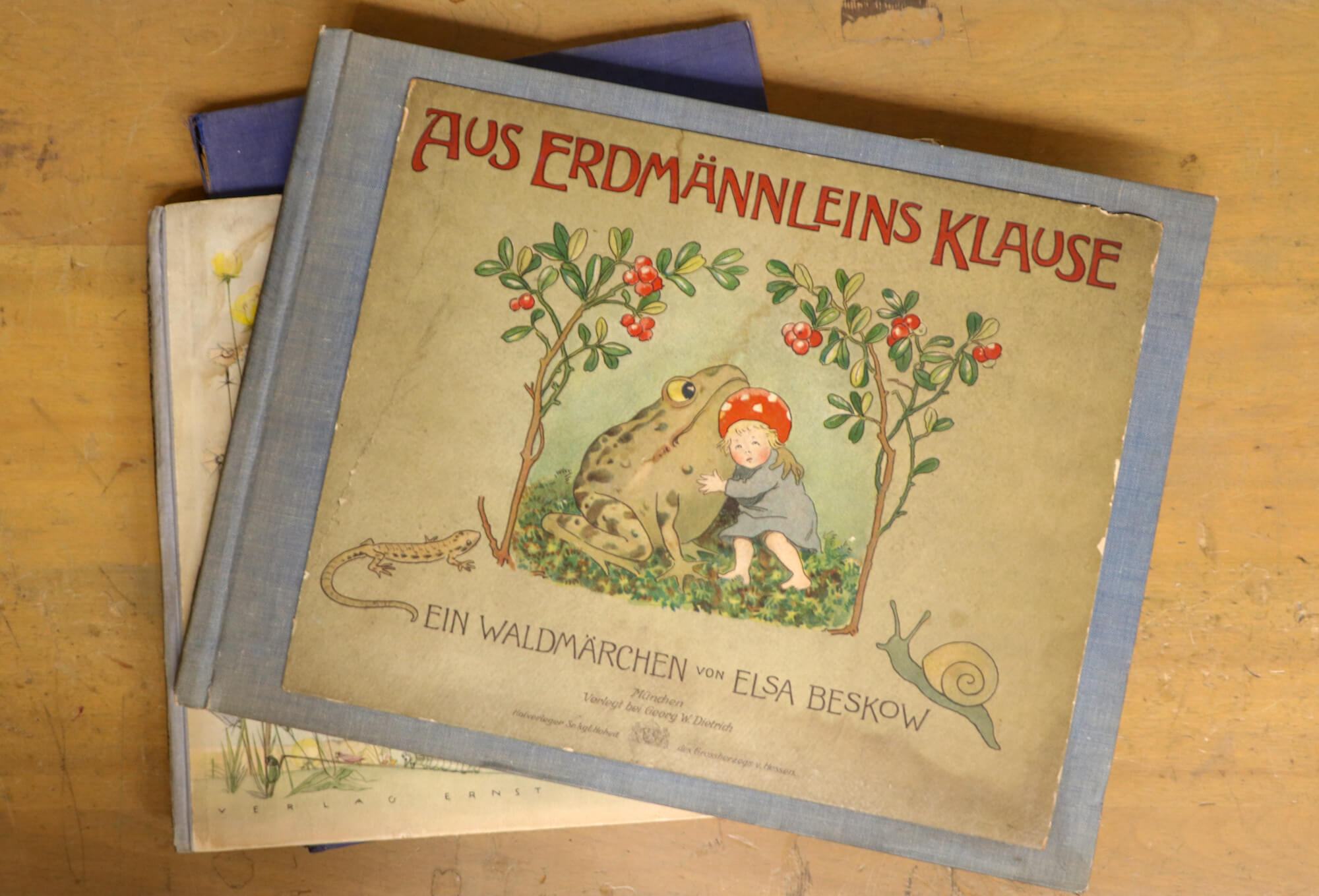

More recently, the “old” and “new” juvenile books were gathered together in the off-limits area to create a collection totaling more than 13,000 books. The “new” collection includes some books that Hunt would have collected specifically for use in the various children’s reading rooms, and reflect her interest in bringing a diversity of books to Brooklyn readers.

There are books in multiple languages, fiction and non-fiction, picture books and novels. Other books that were in circulation well into the 20th century are now also part of the collection, complete with their signed and dated check-out cards.

It’s almost impossible to walk through the collection without getting distracted by old favorites that leap out from the shelf — a signed copy of “The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler,” a first edition of “Stuart Little,” beautifully illustrated copies of “Grimm’s Fairy Tales.”

Some of the more celebrated books are present thanks to Hunt’s national work on behalf of children’s literature. In 1922 she served on the very first Newbery Medal Selection Committee. She ensured that the books that were honored over the years were included in the Brooklyn Public Library by writing letters to authors and asking for signed copies. That tradition continued after her retirement, with the collection including signed copies of Newbery-winning books from the 1960s and 1970s.

While volumes from the collection are occasionally on view, it has largely been inaccessible. Archivists at the library are hoping to change that by raising funds to properly catalogue and evaluate the collection.

In the meantime, if you head into a Brooklyn Public Library branch and spot a children’s reading area, spare a thought for Clara Whitehall Hunt and her contributions towards the literary education of Brooklyn.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless otherwise noted]

Related Stories

- How Brooklynites Fought for Equality Is Documented in the Civil Rights Collection at BPL

- Building of the Day: 10 Grand Army Plaza

- Eager Readers Flock to Get the Latest Books (1900)

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment