Jonathan Lethem Comes Home

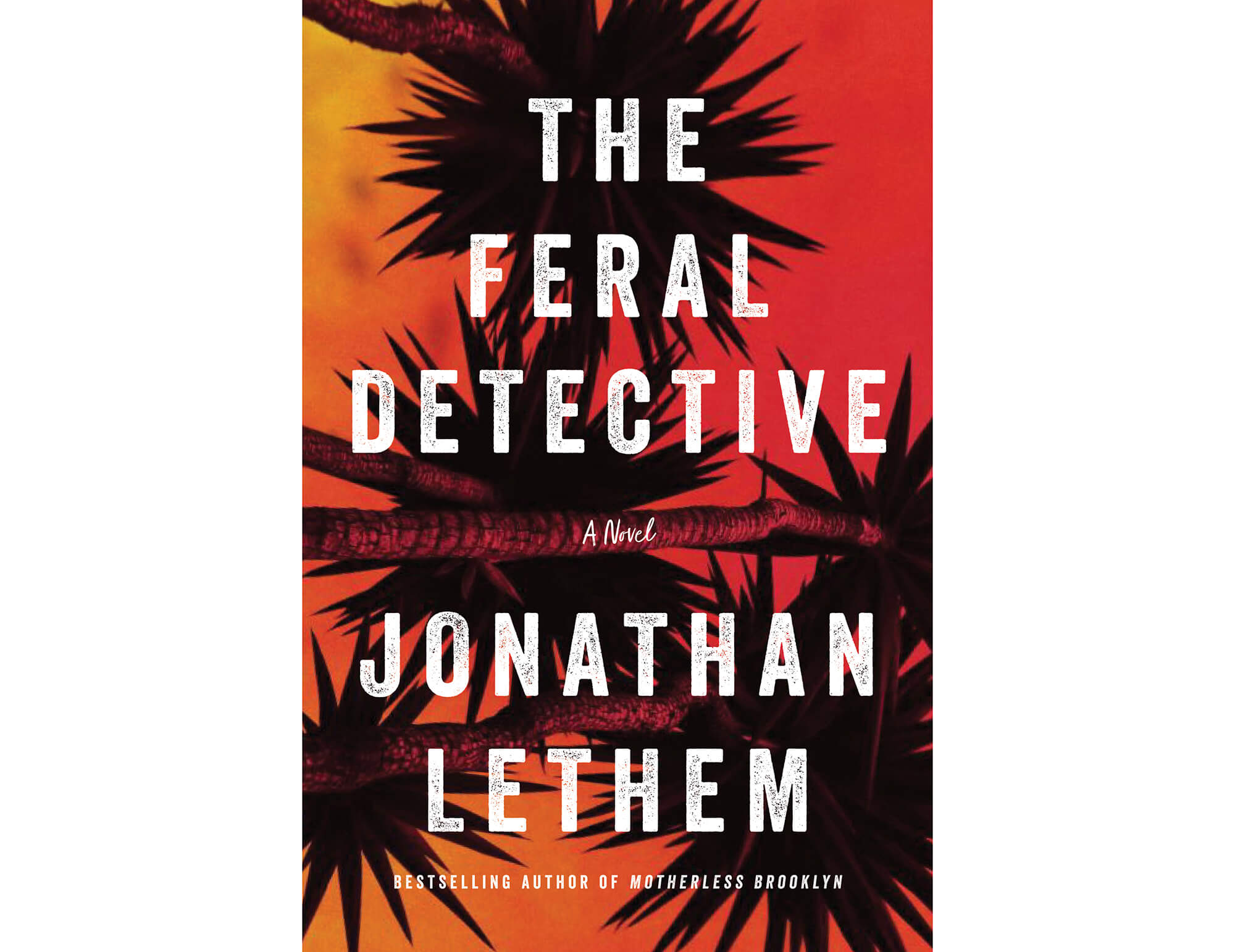

The celebrated author returns to Brooklyn to talk about his new book, “The Feral Detective.”

Jonathan Lethem in Brooklyn. Photo by Susan De Vries

Coming back to Brooklyn has been weird for Jonathan Lethem. He spent the previous night before our conversation walking with his friend, the novelist Christopher Sorrentino. The pair were “just feeling the streets,” Lethem says, trying to get a sense for a place that remains both home and increasingly foreign to them. They strolled all the way from Dumbo, where his publisher had put him up in a hotel, down to Red Hook, doubling back and walking up the Brooklyn Heights Promenade.

It was a strange experience. “Everything is always being utterly overwritten, and yet the palimpsest, the old lines are still there,” he says of the borough where he was born and with which he remains deeply associated. “You just scratch one layer off and it’s shockingly continuous.”

Lethem would know, having had what he describes as “many pasts” here. Raised on Dean Street in Boerum Hill — “North Gowanus” was the preferred nomenclature of his parents, an activist mother and artist father — his childhood memories of the neighborhood would become the focus of a series of novels and essays he produced after returning to Brooklyn in 1998. The journey back to where he started began with a book Lethem now calls “the fun one.” “Motherless Brooklyn,” a rumpled detective story starring a Tourette’s-inflicted gumshoe who was raised in the trash-talking milieu of Court Street, won the National Book Critics Circle award in 1999 and planted the seeds for an incredibly fertile time in his career (it was recently adapted into a feature film, directed by and starring Edward Norton, which will be released in 2019). Lethem was living on Bergen Street at the time, only a few blocks from where he grew up, and was investigating a place that, he says, had for him disappeared while at the same time it was being reimagined as a literary utopia.

The Brooklyn literary scene was in the popular imagination. Despite Lethem expressing mixed feelings about the community that was forming, his writing undoubtedly at this period became energized by the hidden corners and emotional heartbeat of the borough. You can see it in the feverish pace of the work produced during this time, whether stories of frantically zigzagging around Flatbush Avenue or pieces that put a spotlight on local authors such as L.J. Davis and Paula Fox. For one of his most famous essays, he tried to “inhabit and understand the Hoyt-Schermerhorn station as a place” by stalking the subway platform for hours. There was a level of obsession in his writing during this time, which culminated with the 2003 publication of “The Fortress of Solitude,” a zany and magical epic about city life and gentrification. “I ended at the back end of almost ten years of writing continuously of growing up in Brooklyn.”

His connection to Brooklyn remains deep and conflicted. But Lethem, when pressed, admits that he really became a novelist in California. Following a stint at Bennington College in Vermont in the mid-1980s, he spent the next decade, give or take, working in used bookstores in the Berkeley area. It was here that he published his first four novels, inspired genre-obsessed works such as “Amnesia Moon” and “Girl in Landscape” that helped him develop a cult following. And it’s where he returned, both in life — he moved from Brooklyn almost a decade ago, taking a teaching position at Pomona College outside Los Angeles (a chair once held by the writer David Foster Wallace before his death in 2008) — and in work, via the setting of his new novel, “The Feral Detective.”

Built into the book’s detective story is a tension between New York and Los Angeles that is hard not to personalize. Phoebe Siegler, the protagonist of “The Feral Detective,” is a chip-on-her-shoulder New Yorker who gets pulled to California to find Arabella, the missing daughter of her friend Roslyn. On the East Coast is supposed stability, a foundation — Roslyn lives in a “perfect Cobble Hill duplex” on Cheever Place — while the West Coast is lawless, cracking apart. Outside Los Angeles, Phoebe is connected with Charles Heist, the titular detective, who drags her into the desert. There she encounters a world that is stranger than she ever imagined.

A character who is traveling from the known territory of Brooklyn to the expansiveness of California, reluctant at first but eventually finding some kind of peace? On the surface, it reads like an autobiographical sketch.

You remain associated with Brooklyn even though you have not lived here for some time. How many years ago did you move to California?

Eight years ago, almost nine now.

You’ve been back and forth between California and Brooklyn a few times.

Yeah. When I was nineteen I literally hitchhiked to complete the journey. I arrived in California and was like, ‘to hell with all the East Coast hierarchies, all the old-school ties and legacy. Now I’m going to be in the wide-open utopian future.’ It was a hippie dream. I not only thought I would never be a New Yorker again, I didn’t even visit. My family was very exploded at that moment and it was four or five years before I even got on a plane and was in New York City again. I wasn’t tempted to come back at all.

What eventually brought you back?

There were certain people I missed and wanted to see. The future of what I wanted to write about was there and deep old friendships were calling me. When I conceived writing “Motherless Brooklyn,” it was the same moment that I was suddenly making enough money that I could quit my bookstore job. So I came back, without expecting for it to turn into “The Fortress of Solitude” or my career as Mr. Brooklyn. I was like, I’m going to write one book and it’s a funny one. I’m going to remember these streets and the talk on these streets. It seemed like a good assignment to chew on. It ended up rewriting how everyone viewed my writing. Mostly, it chopped off the first four [books]. Nobody remembered them at all!

Does that bother you?

No, no. Time solves all of this. But there were a couple of years where it was really funny. People — for obvious reasons that are completely understandable — who had just read “Motherless Brooklyn” would say, ‘So what’s your second novel going to be about?’ That was my fifth.

As a writer, I sort of became that Brooklyn guy because it was alive. I did, halfway through “Motherless Brooklyn,” realize that I was accidentally waking up these … well, there’s a word for it: traumatic memories. And they were very powerful. Suddenly, I was a writer enough that I could write about that, which I wouldn’t have been until just barely then.

What is it like to come back to Brooklyn now?

It’s a lot of things. When I was writing “The Fortress of Solitude,” and kind of possessing — not repossessing, because in a way it was never mine, it was like possessing for the first time — my legacy material here, I was so activated about it and had this vision of the place in time. I was collecting impressions and locating old friends, people who had never left, people were still sitting on the same stoops where I had left them 30 years before. And it was such an incredible reconstructive, emotional matrix I was in. But that itself is now ancient history.

How so?

It’s incomprehensible how it has changed. I had thought, ‘The white people arrived, the money is here.’ But what innocence, what total innocence to think of 1999, 2000, 2001 as some sort of consummated gentrification when you see where it has gone. This is literally encoded in jokes that people I know will make about how they moved in, bought a brownstone in the late 1990s and felt like they had arrived, and felt guilty or caught in the crosshairs reading a book like “The Fortress of Solitude.” It disinherited them, they would never belong here. But now, 20 years later, the really new people look at them sitting on their stoops or having their block parties with the same contempt or revulsion.

Was that a role of the Brooklyn guy, as you said earlier, something you took on willingly or something you begrudgingly accepted?

It was … a muddle of those things. I think I embraced it. There was a sense of having a cosmic, sensory memory of the place, and I just kept doubling down. All I was doing was investigating my own footprint in this space, and triangulating all my memories with those of all my old friends I had reconnected with because “Motherless Brooklyn” brought every Brooklyn kid I ever went to grade school with out of the woodwork. We all went down those memory holes together.

For a time, I was drinking at the Brooklyn Inn every night and not being modest about the fact that I was the guy with the cred. Nobody was going to walk in there and out cred me, at least for a couple of years. But it was an “untruth,” because all I was in charge of was my own mental drama. But I had a kind of version of modesty. People would say, ‘Do you feel like you’ve written the great Brooklyn novel?’ And I would say, ‘Listen, Brooklyn’s way too big for that.’ It was a stock answer, but I believed it. I was content to have written the great Dean Street novel. Not even that, the great novel of Dean Street between Bond and Nevins. If I did that, I was content.

Do you think you did?

Well, now even that sounds arrogant to me. When I come back now, I have my mind blown again. The sensations, the allure, the ambivalence, all the anxieties, they all flood back and I think about what it was like in the late 1990s when I experienced that on the first return, and embraced it and leaned into it in every possible way. I feel exhausted. I don’t know if I could ever pretend to have the equipment to say all the things I feel about this place.

How do you feel about the Brooklyn literary scene now?

It still strikes me as a superficial but fascinating thing. Right as I happened to be in like year seven or eight of this ten years of living a block from where I grew up, writing about where I grew up, this idea animates around me that Brooklyn is a literary cultural center. Which, you know, I’ve appointed myself debunker-in-chief of this. It doesn’t really have any real substance. Where does it come from? It involves good writers, but they just happened to be living in Brooklyn for a little while, sometimes a very little while. It never struck me as being a literary movement. As artistic-historic movements go, it’s really weak tea. And in my experience, it became analogous to the obnoxious rah-rah aspects of gentrification. But it was one that I was unfortunately implicated in [laughs].

Did you consciously remove yourself from it?

Well, I mean, it took me a while to figure out how to say something even as muddled as what I just said to you. I was inside this thing as it formed, it seemed a little like hokum to me, but of course, I was enjoying the benefits of it in many ways. It was confusing. But in retrospect I did run away, quite a bit. In ways people are aware of, I lived in Toronto for parts of two years, I was going to Yaddo, and then I started running up to Maine and fell in love with this place I now go to in the summer. I did find this cathexis where I had fused myself to my old block and was starting to look for exit doors again. I became a secret part-time citizen. I was out of town a lot.

Was the work following “The Fortress of Solitude” attempts to construct exit doors out of Brooklyn?

Of course. I was saying, ‘Can we please stop talking about Brooklyn?’

And then you left. Was the tension between New York and California in your new novel, “The Feral Detective,” born out of that transition?

Well, first of all, the tension between New York and California was something I was enmeshed in before I ever went to California. As a kid growing up, I was so identified with New York, so moored in this place. California has a symbolic function in the American psychic imaginary that was always really, incredibly alive for me.

What pulled you away from Brooklyn a second time?

I get this call to put myself in the conversation for the Disney Chair [at Pomona College]. I was a sophomore-on-leave from Bennington College. I not only didn’t get an MFA, I didn’t get a BA; I had to do a lot of pinching myself. And it was unbelievably lucky timing. A second kid had just come along and health insurance and the ability to not have to go on living off my credit cards from time to time, to be a solid citizen, was really valuable. I moved because I decided if I’m doing this thing I’m just doing it. I’m not going to play footsie with this job. The professors all live in Claremont, near campus. I’m all in.

That’s a big shift.

It’s not a place you would go to live for any other reason. Especially me, at that point in my life. And where I ended up was a conundrum. It’s a very placid, attractive, anodyne eastern suburb of Los Angeles that’s built around the colleges. It didn’t conform to any of my fantasies about the West Coast. And it also wasn’t palm trees and the blue horizon. It wasn’t the ocean. I’m like two hours from the ocean. It’s really not what people think of when they think of Los Angeles. Initially, I was there with very young children and a big new job, and all I did was figure that out, just live.

And when did “The Feral Detective” start to be developed?

About five years ago, I started to lift my head up a little more. The kids were a little older and I was more relaxed about my job. And I was like, ‘What is this place I’ve come to?’ It’s as Midwestern as it is L.A. Where I was living had nothing to do with that. It had a lot to do with the desert. Claremont is the last thing before you’re in a very different geography. You’re suddenly in Riverside and Redlands. You push past that and you’re in Palm Desert and Joshua Tree and Yucca Valley and the Mojave. I can be in Joshua Tree in half the time it takes me to get to the Pacific Ocean.

And that place is crazy. It was symbolically wide open and off the grid and so really innately anarchistic, and at the same time, it was abutting this unbelievable monolithic suburban conformity. Some people were sort of doing both, weekending anarchists.

So it was conceived, in some way, before the arrival of Trump.

I was assembling this material in my head for quite a while. I figured I would probably write it as a present day book, but it didn’t seem importantly tethered to history as I was preparing it. Well, like everyone, what I was working on or thinking about in November 2016 looked really pointless. So I spent a few weeks thinking, ‘Why would I write that? Why would I write anything?’ Then suddenly, I turned the material over another way and it looked to me like, at the very least, a vehicle for making some angry jokes about what had just happened. That, maybe, I could get it up on its feet by starting that way. And then it started to seem, actually, it was a very lucky opportunity, the fantasies about running out of this American space into some other space were really congruent with how that made me and a lot of people I know feel.

And, what’s more, I had figured out Phoebe’s voice pretty quickly. She was a woman, so she could be pissed off in a [direct] and relevant way. Without completely acknowledging it, I had been assembling a plan for a book about men and women, about gender. So that was also opportunity presenting itself.

Despite the character being a woman, how much of the voice of Phoebe is your own voice?

I would say there are whopping parts of me in Phoebe, in her voice and sensibility, and generationally. Also, she was working at the Times … not to promote my political astuteness at the expense of my character, but I think she was a little more complacent that everything would be just fine if Hillary [Clinton] was elected than I personally was, but that’s representative. And that’s representative even of a part of me that was slumbering, thinking, ‘Oh, well, that’s not too perfect, but of course that’s what needs to happen.’

No matter what, it was hard to get away from that kind of thinking at that exact moment.

Exactly, she enshrines that moment. And, you know, in terms of its view of that — it’s not like I’ve written a comprehensive book about anything in the political landscape. I just wanted to capture the particular acrid flavor of the ten days before and after his inauguration. All I wanted to do was make a snapshot. And, the extraordinary exhilaration, which is now in itself a non sequitur in some ways, of the women’s march. What does it mean to feel all of that? How do you hold it? How do you go on holding that you felt all of that? I wanted to make a snapshot.

I wanted to circle back to some of the class dynamics of the book, which bubble up to the surface as the novel progresses.

You can see me gnawing over this in the book. On the one hand, there is the American myth that we live in a classless society. Many people have debunked that, but it’s still a permanent form of American self-delusion and amnesiac narcissism that we play, that anybody can be a millionaire. I can critique it; it’s also in me. That’s a baseline issue. On top of that, you have the identity of being from the New York I grew up so completely involved in and alive to, which was, you know, my grandmother was the great champion of, ‘We live in the great city of immigrants!’ Everybody, cheek by jowl, just fighting it out and getting to know each other, so diverse, the cab driver with the stogie can talk back to the millionaire in the back of his cab. It’s all incredibly egalitarian.

Yes, and also no. Right? As somebody who has escaped this city, I think this is a very stratified and very hierarchical [place], even compared to some other parts of America. And there are the kinds, to me, of permanently beautiful, fascinating, raw and conflictual energies that are created by the compression in New York City. The cheek-by-jowl thing is real, that’s one of the things that energized “Motherless Brooklyn.” On the streets, everyone is bumping up against one another and generally opening their mouths. That’s amazing to me and very rich.

But on the other hand, I find this place very deluded about how much the old school, secret handshake, Ivy League hierarchies really run the town. And an interesting thing about being in a place like Southern California, and specifically the Inland Empire — well, it’s not New York, you don’t have those energies, the obvious results of that compression, the different kinds of people living in the same apartment building. In some ways, it’s much more segregated, you know which town is the rich town — Claremont is well off, Pomona is not.

But, at another level, the American egalitarian proposition, in some ways, can be enacted in that blandness and with the distance from the old legacies and the old East Coast hierarchies. In some ways, something really authentic can happen that is more egalitarian. You don’t really see as many different kinds of people walking down the street, but then again, where the kids go to school in New York City seems to me as segregated or more so than it was when I went to school here in the 1970s. My kids, I’m bragging now, they go to a public school in Claremont that’s the zoned public school. There are a lot of immigrant children. If I stayed [in Brooklyn], I would have faced that St. Ann’s vs. P.S. 29 fork in the road. And even P.S. 29 is a quasi-private school from all the energies that surrounded it. Where I live now, it might be bland in many ways and there’s a kind of cultural vacuity but it also is fulfilling an actual American egalitarian concept that New York lies to itself about, and that is intriguing to me. You’re just so much further from the organizing, hierarchical powers that it’s kind of like, ‘Well if you live in Claremont your kid goes to that school.’ You really don’t know who went to Harvard unless people tell you.

Class exists in America. You constantly have to revert to this position. And I benefit from my class position, where I live now as I did in New York.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Fall/Holiday 2018/19 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- ‘Brooklyn Photographs Now’ Captures the People and Places of a Changing Borough

- New Book Details Rise and Fall of Iconic Brooklyn Store Abraham & Straus

- Shop Cats of Brooklyn and Beyond Finally Get Their Due With New Book

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment