Small Businesses Inside Clark Street Station Worry About Survival With Eight-Month Closure Ahead

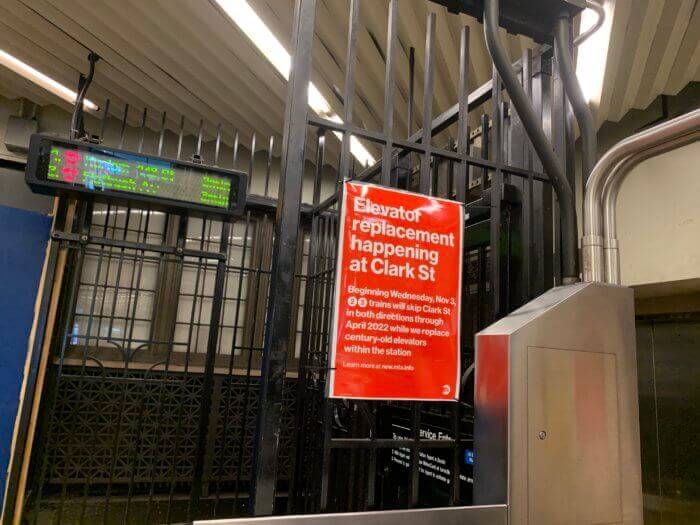

The MTA announced last week that the station will be fully closed starting November 3 as the station’s three aging elevators are replaced after years of frequent breakdowns.

Photo by Kirstyn Brendlen

Small businesses on the upper level of the Clark Street subway station are bracing for an eight-month closure starting next month.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority announced last week that the station will be fully closed starting November 3 as the station’s three aging elevators are replaced after years of frequent breakdowns.

Commuters are being encouraged to catch trains at the nearby Borough Hall and High Street stations, but for a handful of shops inside the station at street level, the closure means more than a temporary change of plan.

“It’s going to be a disastrous thing for our businesses,” said Thomas LaMarca, who runs The Cutting Den, a barber shop inside the station.

The upper level will remain open even as trains skip the station so customers can access the stores, but LaMarca said he has regular customers who live in Park Slope and Kensington who stop for a haircut on their way in and out of the station. He doubts those customers will make the trip to Clark Street on foot from the nearby subway stations, especially once cold and snow settle in.

Salahuddin Aziz, who owns a nearby newsstand, had similar worries. Most of his customers, stopping in for a cup of coffee or a snack, are drawn in because of the store’s proximity to the train, and the pandemic has already brought business to a crawl, he said.

“I’m losing money,” he said. “Plus this? I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

Aziz and LaMarca both said they would have preferred that the MTA had chosen to repair the elevators one by one, which would have kept the station open but extended the timeline for repairs from eight months to about two years.

Ultimately, despite feedback from the community favoring the longer partial shutdown, the MTA chose to shutter the station completely. The station needs at least two functioning elevators to operate safely, the agency said in a press release, so if one of the two left running went offline during construction — as they have frequently in recent years — they would have to shut down the station unannounced until it could be repaired.

“The transit authority, the MTA doesn’t really care about stores that are around here, or else they would pay our rent for us,” LaMarca said. “We’re going to have to pay part of the rent, not all of the rent. We cannot pay all of the rent, because we cannot stay in business then.”

His grandfather opened the shop in 1926, he said. Even if moving to a new location outside the station was possible, he wouldn’t.

Eddie Kandov runs a shoe repair business next to The Cutting Den. A friend of his, who owned a since-shuttered store in the Clark Street station, regaled him with stories of the station’s four-month closure in 2000 — during which business was “completely dead.”

After he heard about the impending closure, he got an offer to go work at a different store for a few months, which would at least provide a steady paycheck. He went to the landlord to ask if he would be able to close the shoe repair temporarily.

“I cannot pay rent, I cannot make money to live,” he said. “I tell him, ‘When they close the subway, can I close the store?’”

“He said, if you want to close, close, only when you come open, you’re going to pay, you cover it,” Kandov said. “For eight months, ten months, how can I cover the rent?”

For now, he plans to stay open for a while and see how business fares come November. Then, he said, he might consider leaving.

Aziz feels that the MTA should step in to help out him and his neighbors.

“They should do at least something for us, you know?” he said. “If they don’t do anything, everybody’s going to be out of business.”

MTA spokesperson Andrei Berman told The City in May that the agency had given their retail tenants in other stations “major rent deals.” The retail space on Clark Street, though, is owned by a different landlord — not the MTA itself. Because they’re not the landlord, an MTA representative told Brooklyn Paper, they can’t offer those same deals or offer much assistance — tenants have to work it out with the company that does own the stores.

Lara Birnback, the executive director of the Brooklyn Heights Association, said the organization will be making an effort to direct customers into the stores throughout the next eight months.

“We’ll do our best to remind people that those businesses are still there, that they need our support, that they should walk a couple blocks out of their way to visit them,” she said. “While I certainly recognize that that’s not the same thing as having a fully open station, hopefully it will help and contribute.”

She’s asked local elected officials to reach out to the businesses inside the station with information about loans or government assistance, she said, and was planning to stop by to talk with business owners to encourage them to reach out to the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce and the city’s Department of Small Business Services to see what they might be eligible for.

“It’s tricky to find government assistance for private enterprise,” she said. “It’s not something that is easily done.”

Aziz took out loans to stay afloat during the pandemic, he said, and now worries about paying them back.

“I used my money, I used my wife’s money, my son’s money,” he said, while he rang up a customer, “It’s not easy, this time. After next month, I don’t know.”

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran in Brooklyn Paper. Click here to see the original story.

Related Stories

- Three Months of D Train Service Cuts Are Coming to Brooklyn

- Frustrated Locals Push for a Second Exit at Dumbo’s York Street Station

- Work Set to Start on Sand Street and Wythe Avenue Bike Lanes

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment