‘Soul of a Nation’ at the Brooklyn Museum Delves Into Black American Art in a Radical Era

The exhibition, on view at the Brooklyn Museum through February 3, is the latest in a recent profusion of museum exhibitions that address the inadequate representation of African-American artists.

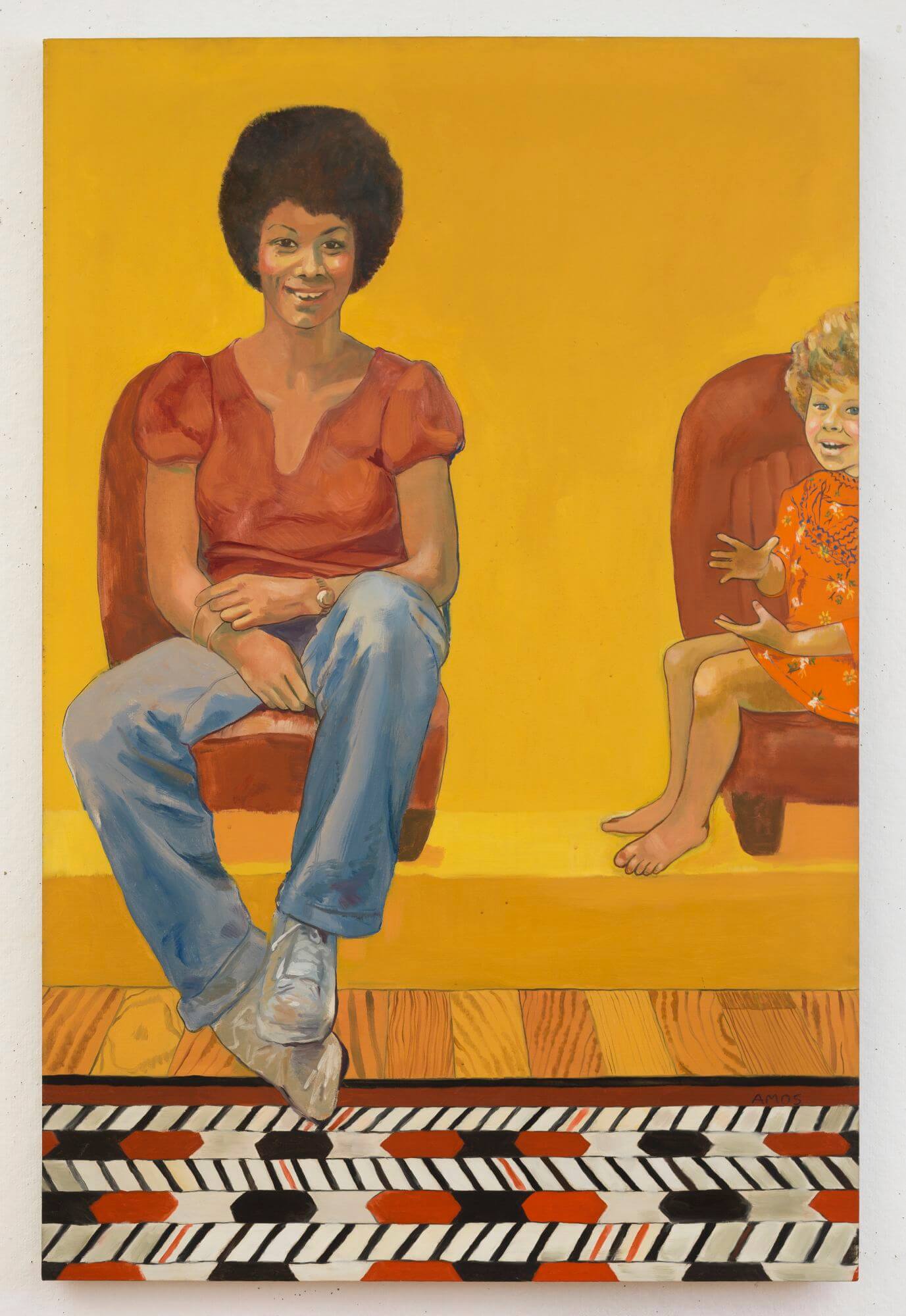

‘Black Children Keep Your Spirits Free,’ 1972, by Carolyn Lawrence. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Michael Tropea

“Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” a traveling exhibition currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum through February 3, is the latest in a recent profusion of museum exhibitions that address the inadequate representation of African-American artists. “The story of art in America is incomplete without acknowledging black American artists,” curators Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley write in the exhibition’s catalog, which was published in conjunction with the show’s initial run at the Tate Modern in London in 2017. This exhibition, they add, “seeks to make that presence — and that vitality called ‘soul’ — resolutely seen and felt.”

Covering the robust period between 1963 and 1983, the exhibit “affirms the fact that black artists existed on the front lines of radical artmaking practices,” says Brooklyn Museum Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art Ashley James, who helped coordinate the show’s latest incarnation. Instead of organizing the artists’ work chronologically, the show moves through the wildly different kinds of art that were being made and how the works were produced. Its biggest argument is against the grouping of the artists as a unified whole, working under the same sets of circumstances and concerns. “Soul of a Nation” offers room for divergence and multiplicity.

The starting point for the exhibition is Spiral, the groundbreaking African-American artist collective active in New York between 1963 and 1965, and the show moves through a variety of names and groups both well-known and underappreciated — Emory Douglas, Faith Ringgold, Barkley Hendricks, Roy DeCarava, Betye Saar, Senga Nengudi and David Hammons, to name only a few.

Bringing the show to the United States for the first time provided the “opportunity to delve even deeper into the specificities of the moment,” James says, including “further drawing out regional distinctions” and reactivating the “aesthetic debates of the time, many of which were being generated within a New York context.” The exhibition ends with a focus on New York gallery Just Above Midtown (JAM), a commercial space created by Linda Goode Bryant in 1974 dedicated exclusively to work by artists of color.

“Soul of a Nation” aims to act as the latest corrective to the underrepresentation of non-white artists. This work will be new to many. For others, it’s a long overdue spotlight. “For some, this is a ‘reconsideration,’” James says. “But for many artists, art historians, and others this is another welcomed affirmation of what we’ve long understood to be the case” — that the work deserves attention.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Fall/Holiday 2018 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Catch the U.S. Premiere of a New Jean-Michel Basquiat Documentary at Brooklyn Museum

- The Radical Women Excluded From Art History, Now on View at the Brooklyn Museum

- Artists Showcase Their Craft at Brooklyn Museum This Weekend

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment