Walkabout: Calvert Vaux, Architect, Part 1

Read Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4 of this story. One of my big regrets about leaving Brooklyn is that I never really got to be an expert on Prospect Park. I just never went there enough to become one. My forays into the park were infrequent, and I never got to really explore…

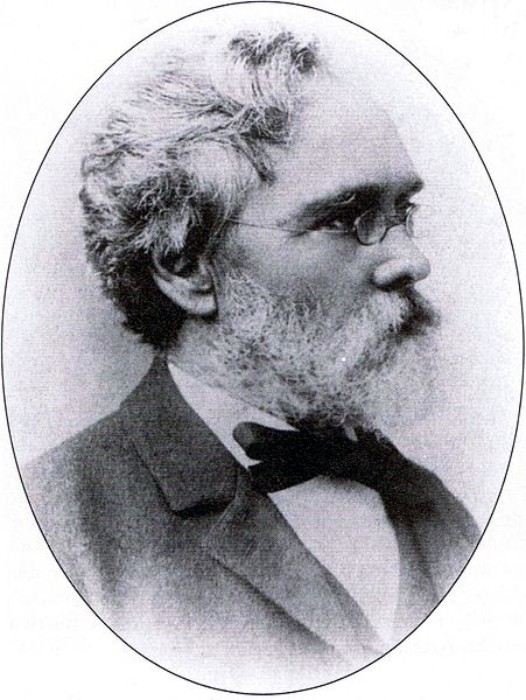

Photo by Suzanne Spellen

Read Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4 of this story.

One of my big regrets about leaving Brooklyn is that I never really got to be an expert on Prospect Park. I just never went there enough to become one.

My forays into the park were infrequent, and I never got to really explore the depths of the park, with all of its wonders and hidden places. I’ve probably seen most of the major landscapes, bridges and buildings, but I never had the chance to make them my own, in daily or weekly walks during all of the seasons, with all of the beauty that that brings.

Prospect Park was just too far away, not terribly convenient, public transportation wise, and there was never time. And besides, I thought I had all the time in the world, I was never leaving Brooklyn. Ah, well, you never know…

I do vividly remember my first solo walk in the park, a long time ago when I was just discovering Brooklyn and when I was rather dangerously naive. I somehow ended up on a back trail somewhere, in the woods, surrounded by bushes, trees and overgrowth.

I distinctly remember realizing that for the first time since I moved to New York City, I was completely alone. There was not a soul around me. I was alone in the middle of a huge park in a huge city of millions of people.

I grew up in the country, and used to wander around in the fields and woods near my home, so being alone in nature was not new to me. But alone in the middle of Prospect Park in the early 1980s? I was quite uncharacteristically freaked.

I hauled butt out of there and didn’t relax until I saw people again. So much for the country girl, I had become a paranoid New Yorker.

Most people don’t know a lot of things about the great city of New York that they live in, but many people do manage to know that the same pair of landscape architects designed both Central Park and Prospect Park, sometime back in the 1800s.

They may even recognize the names: Frederick Law Olmsted, which is a kind of cool name that rolls off the tongue, and Calvert Vaux, which does not roll off the tongue at all. How do you even pronounce “Vaux,” anyway? (It rhymes with “hawks”)

Depending on whether or not you live in Brooklyn or Manhattan, you may also think that Central Park was designed and built first, which is correct. You might also think that Prospect Park is a better park, and that Central Park should be considered just a practice run. You would be correct again, and that’s not just the Brooklyn in me talking.

Olmsted and Vaux designed a great park, an oasis from urban life, a huge expanse of natural beauty in the middle of the city. A natural patch of nature with fields, woods, a large meandering body of water, crisscrossed by pathways and roads, dotted with buildings and bridges that are natural resting places for tired feet.

Yeah, right. A cynic might say it’s all as fake as Disney World; a man-made and created paradise. But who cares? So who was this Calvert Vaux guy, and what made him, and his partner, so good at putting together a park, anyway?

Calvert Vaux, the great American park maker was British, born in London, England, in 1824. His father was a surgeon, and the family lived on Pudding Lane, near the London Bridge.

The family, which included his parents, a brother and two sisters, lived comfortably, but his father died suddenly, when young Calvert was eight. He was still able to continue his education in local public (private) schools, but the family’s fortunes were quite diminished, and they soon moved to a less desirable neighborhood.

At the age of 19, Vaux began studying architecture with Lewis Nockalls Cottingham, one of the more important members of the English Gothic Revival movement of the early 19th century.

Cottingham was responsible for the restoration of several of England’s best Medieval Gothic buildings, including the Chapel of Magdalen College, Oxford; Rochester Cathedral; St. Alban’s Abbey; and the Temple Church, London, all restored between 1829 and 1840.

In addition to his restoration expertise, Cottingham was also a prolific architect, responsible for not only his own home in London, but for several important country estates, city houses, banks, hotels and commercial buildings.

He even laid out roads and dabbled in city planning. Apprenticing to Cottingham was a great privilege and a joy. He was a fine teacher, and by all accounts, an easy-going and affable man who loved what he did for a living, and taught his apprentices the same.

His London home was also an extensive library and museum, with plaster casts of friezes and architectural details of famous buildings, many of which he had worked on. He collected bits and pieces of classical and medieval architecture, as well as furniture, lighting and other furnishings, all collated in chronological order and meticulously labeled and explained.

His apprentices were able to see firsthand how the masters of old had designed and constructed buildings, and they learned about the different materials and methods of interior and exterior construction. Vaux absorbed everything, and honed his considerable talent during his years with Cottingham.

Although his education was first rate, it was cut short by Lewis Cottingham’s illness and eventual death only a few years into the apprenticeship. During those years, Vaux had become friends with another apprentice, George Truefitt, who was soon to outdistance his master.

In the beginning of 1846, Vaux went on a tour of the Continent with Truefitt, who persuaded his friend to concentrate on his drawing. In his own drawings, Truefitt had an excellent eye, a gift for detail, and the ability to place his buildings within their environments in the best way as to showcase both the site and the building, a talent that Vaux learned from his friend and made his own.

Vaux began to see the forest and the trees, and took notice of the natural environment and how architecture worked within that environment. It was a transforming education.

In the years following 1846, when the two men came back from their tour abroad, Truefitt’s career took off. He published several books of his architectural drawings and was soon a busy professional. Vaux was not as fortunate. He got some work, but he was not the raging success that Truefitt was.

His friend got him some jobs, but Vaux was looking to make a name on his own. He was suffering from the same fate as many budding American architects in the middle of the 19th century.

He had apprenticed with a well-known professional, had honed his skills as an artist, but the profession of architect still had not gained the respect of society. Most architects were seen not as professionals, but as jumped-up builders and tradesmen.

Vaux supplemented his income by working as a letterer for a map company. He was able to write backwards with great ease, a skill necessary for printing, and could have survived on that, but he was eager to grab an interesting opportunity when it arose.

To that end, he had entered a series of landscape watercolors and drawings made on his trip with Truefitt in an exhibition at a London art gallery in 1850. The paintings and sketches showed well, and caught the eye of the American master of landscape architecture, Andrew Jackson Downing, who was on his own European lecture tour.

At the time, Downing was at the peak of his reputation as one of America’s finest horticulturists and landscape architects, earning the title of the “Father of American Landscape Architecture.” He had already published A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, in 1841, the first book of its kind in America.

He and architect Alexander Jackson Davis had collaborated on a pattern book called Cottage Residences, in 1842, an extremely influential book that introduced the Carpenter Gothic and Hudson River Bracketed styles of homes to the American public.

Downing had gone on to write several more books on horticulture, and was a frequent contributor to landscape and horticultural publications. England’s famous gardens and grounds were a natural start for his European tour, and he certainly would have had an eager audience for his lectures.

Downing greatly admired Vaux’s artwork, and sat down for several conversations with this talented young man. As they spoke, both realized that they shared many of the same ideas about landscaping, architecture, and life in general.

Vaux saw a man with whom he could grow professionally, as well as someone older who could be a mentor, but young enough to be a friend. Downing saw a younger version of himself, and a man whose talents were being stifled by the British architectural world.

He offered Calvert Vaux a job in the United States, at his offices in Newburgh, NY. He wanted Vaux to be the architect to his landscape architectural practice.

Vaux, who was unmarried, unattached and eager for a change and a chance to grow, took up that offer, packed his things, and moved to the United States.

Later in 1850, Calvert Vaux stood on the shore of the Hudson River in Newburgh, and gazed across a gorgeous landscape that would be his home for the rest of his life. He was at the beginning moments of a momentous career.

Next: The rest of the story.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment