Architect and Urbanist Vishaan Chakrabarti’s Vision for Brooklyn Connects the Future to the Past

Chakrabarti has become a prominent voice in the debate over how our cities will be constructed in the face of global warming, a housing crisis and increased gentrification.

Chakrabarti in his Union Square office. Photo by Susan De Vries

In a small office in a nondescript building a few steps from Union Square, the architect and urban designer Vishaan Chakrabarti is thinking about the future. And not just the flight to Venice he has to catch that evening — he has become a prominent voice in the debate over how our cities will be constructed in the face of global warming, a housing crisis, and increased gentrification.

Born in Calcutta, Chakrabarti and his family emigrated to the United States in 1968, when he was three years old. After a brief stint in Arizona, they ended up settling in Arlington, Mass., outside Boston.

“I hated every minute of it,” Chakrabarti says. He majored in both art history and engineering at Cornell, and followed it up with a graduate degree in city planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a second graduate degree in architecture from the University of California, Berkeley. “It was a convenient way of hiding from the recession in the early ‘90s,” he adds jokingly.

His multi-faceted career has spanned city planning, development, architecture, and academia. Chakrabarti helped envision the High Line while he ran the Manhattan Office of City Planning under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, is a professor at Columbia, and published A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America in 2013. More recently, he created an alternative proposal for fixing Penn Station.

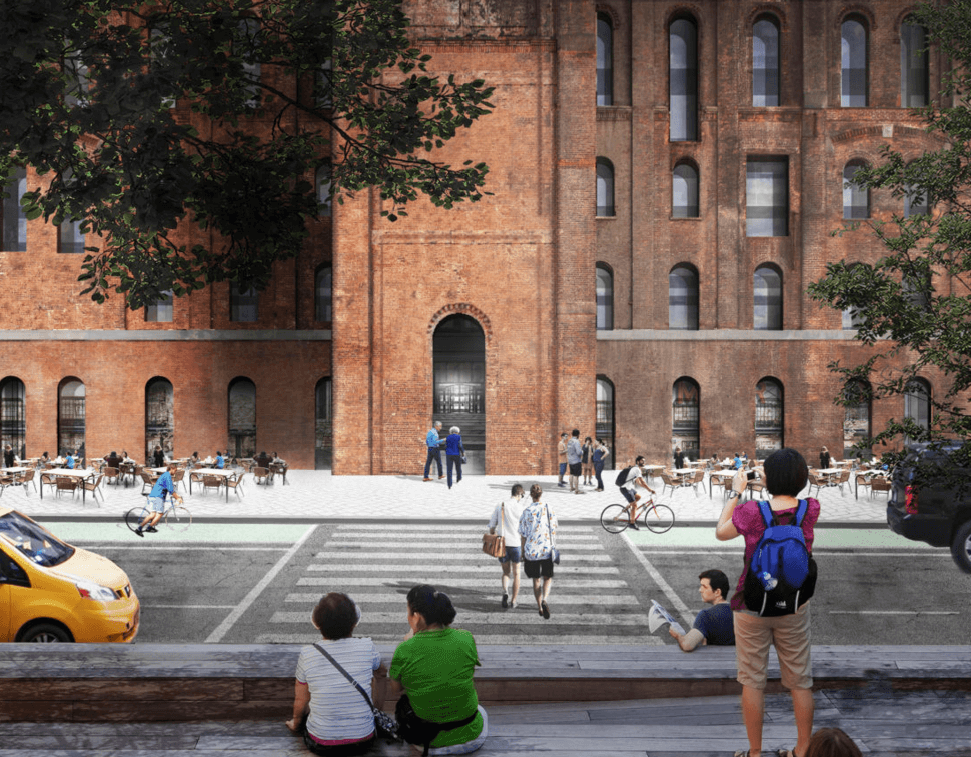

As a principal at SHoP Architects and now head of his own firm, Practice for Architecture and Urbanism, his biggest project to date has been the Domino Sugar Refinery redevelopment. He helped conceive the master plan for the mega-project while at SHoP.

In recent months, developer Two Trees commissioned him to rethink the adaptive reuse of the landmarked 1880s refinery building; his unexpected and controversial design was approved by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in November.

In conversation, Chakrabarti — concise and particular with his choice of words — is eager to talk about his vision for a new Brooklyn. For him, this consists of a rethinking of the borough’s infrastructure and a commitment to development that is rooted in history, which will help increase jobs and building of what he calls a working waterfront.

What’s your vision for the future of Brooklyn? What does it need?

That’s a big question. If on its own, Brooklyn would be the fourth largest city in America. On that metric, it’s underserved in almost every capacity. It needs more cultural infrastructure, it certainly needs more affordable housing, and it needs more open space.

The general public falls asleep when you talk about the word infrastructure, but I think that’s partially because we talk about it along such a narrow bandwidth — transportation, sewage systems, electrical systems, water systems. In my book, I talk about an “infrastructure of opportunity,” which is all of those things but also things like affordable housing, cultural space, parks, and health care. Basically, all of the things that when combined together create social mobility.

I think City Hall’s trying but catching up to the social infrastructure needs of the population is hard. I think the demand constantly outstrips the supply, in terms of social infrastructure. That’s the issue — keeping up with the number of school seats, keeping up with the number of subway of trains we need.

I took my family to Japan a couple of years ago and I noticed that they now run the bullet trains between Tokyo and Osaka at six-minute headways, which I just find amazing. When you see that stuff around the world you understand how behind we are. So that’s where I would definitely start.

How are you approaching Domino?

When I travel, the two things people always ask me about are the High Line and Domino. Both of them represent kind of new neighborhoods but ones very much grounded in history. I think that’s what a lot of city dwellers are looking for right now.

People understand that cities are growing, more people are coming, and big buildings are going to get built. Not everyone is a NIMBY but people don’t like it when they feel like anonymous towers that could really be anywhere are dropped in their neighborhood.

I consider myself a preservationist. For some people in the architecture profession, building some spaceship out in the desert somewhere in Abu Dhabi is what gets them all jazzed. That doesn’t get me jazzed in the slightest — I’m much more interested in what is the existing fabric of a place and how do you build upon that.

Have you faced resistance?

The master plan passed the community board overwhelmingly. One of the things the resolution specifically asked for is that the buildings not be all glass. So, the first building that has gone up is copper and zinc, which were both materials that were found on the Domino site that patina.

Our design for the sugar refinery is different. It’s not about the materials, it’s more about the relationship of how the old building sits with the new building, and kind of the way in which the two talk to each other.

What’s most important about building in Brooklyn?

Mixed-use is critical. Obviously, the city is in the midst of a huge affordability crisis. I can’t talk about it too much, but I think we’re going to end up building quite a bit of affordable housing in Brooklyn, and I’m very proud of that effort. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the occasional luxury condo building, but that’s not what I spend most of my day working on.

Recently, I’ve become very interested in this talk about the death of retail around Amazon. But what Amazon’s really killing are the big chain stores. People are still interested in local retail; they shop for experience. Does that mean the ground floor of buildings can see different kinds of uses?

What are the concerns with building on the waterfront?

Obviously climate change is first and foremost. One of the things we did during the master plan was pull the buildings back from the water. We created more parkland, and the park surface is porous, it absorbs water more.

Beyond that, what’s most important is bringing back the working waterfront. In the 2000s we began to see a rediscovery of the waterfront, but then it became inhabited by luxury condos and rental buildings, and problems like the “poor door” issue, which is an abomination. I would love to see more industry return to the waterfront.

Domino is very consistent with the way Jane Jacobs thought about cities, in terms of mixed-use, and when it’s finished it will have a school, a community center — it will be a 24-hour space. What we’ve seen a lot on the waterfront is mono-use. When you have a luxury tower with a Duane Reade on the bottom, that’s not what Jacobs meant by mixed-use.

I think what people fear with new development is an erosion of identity and a sense of placelessness. I think by reinforcing the identity of the place — everyone understands that it’s changing. The sugar refinery workers are in Yonkers now, they’re not in Brooklyn. It’s the same thing as the Brooklyn Navy Yard or Industry City, which have come back to life.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Fall/Holiday 2017/18 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Domino Sugar Refinery Redesign Approved by Landmarks Preservation Commission

- A Brownstone Dweller Brings Back the Glorious Details on a Distinguished Bed Stuy Block

- Williamsburg Chef Missy Robbins Finds Time for Cookbook, Second ‘Burg Eatery, Life

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment