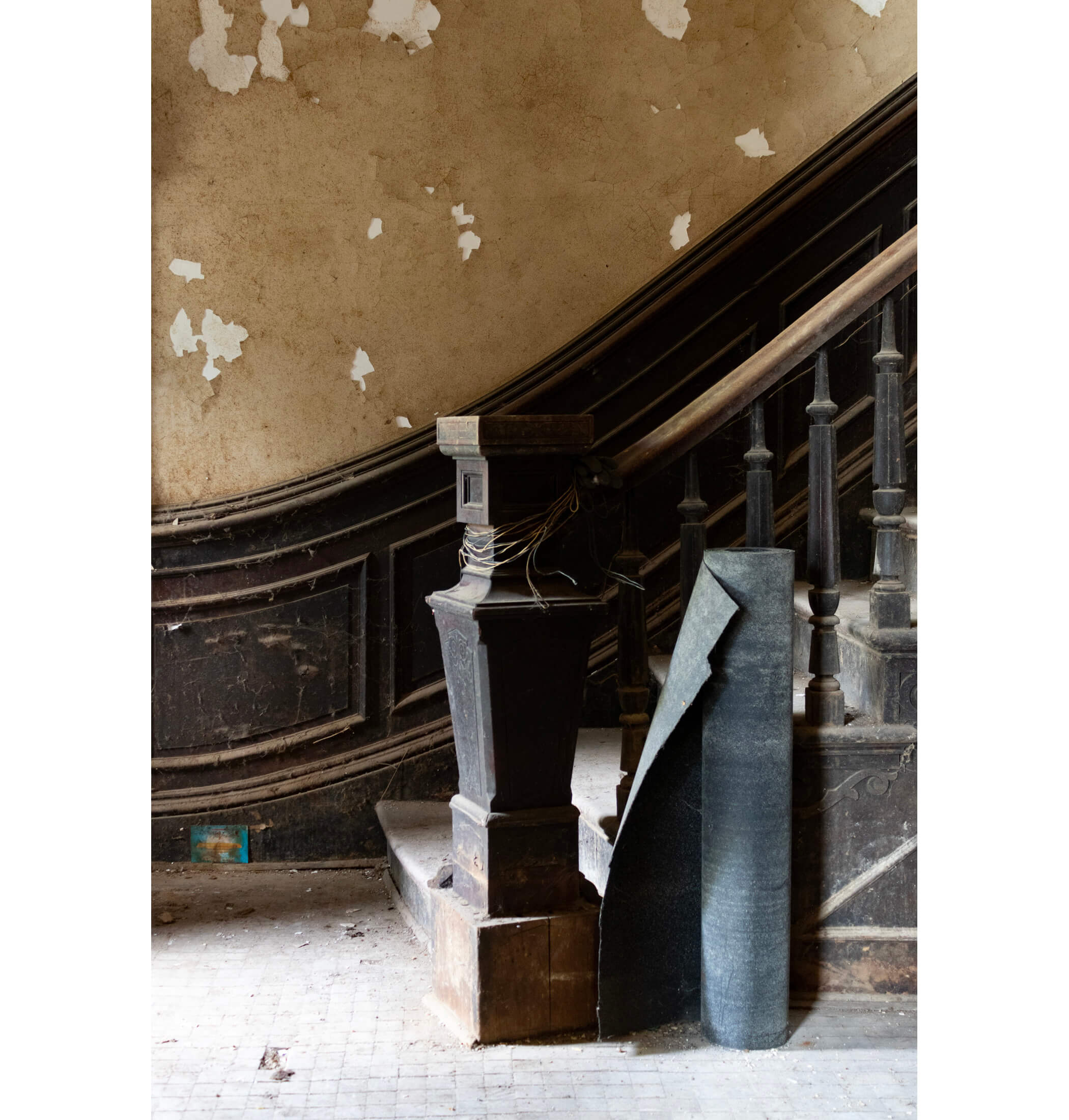

The Decaying Splendor of a Fort Greene Manse

With broken windows and a boarded-up front door at the top of a once grand stoop, the 1860s Italianate gives up few clues as to whether any tantalizing remnants linger on the interior.

Photo by Susan De Vries

It has been slowly crumbling for years. With broken windows, a boarded-up front door at the top of a once-grand stoop, and a trash-strewn yard, the 1860s Italianate across from Fort Greene Park gives up few clues as to whether any tantalizing remnants linger on the interior.

Walking gingerly through dim and dank rooms thick with dust on a recent tour of the interior showed that a bit of glory still remains inside 176 Washington Park, despite years of water damage. Chunks of plaster detailing cling to exposed lathe, pieces of parquet buckle up from damaged floors, tiles glimmer around ornate mantels, and a grand staircase gracefully curves upward, lit by the remaining sections of a stained-glass skylight.

Built circa 1868, the townhouse was put on the market in 2019 after years of legal wrangling over a stolen deed. The heirs of Joseph Tremmel, the last owner, sold the house to an LLC in June of this year for $3.7 million. New owners Shape Capital with Kane Aud Architecture and Urban Design are tackling the project to make the house, located within the Fort Greene Historic District, livable once again.

The first steps included critical roof repairs and hauling out of loads of trash this summer. Amongst the debris were a few items, like old letters, that could be salvaged. With the rooms cleared, some of the details emerged more clearly, providing clues to the layers of history and lives of the inhabitants in what was once an impressive interior.

Some of the details, like the grand stair and stained-glass skylight, clearly date to when the house, on a prime corner lot, was first constructed by T.B. Jackson. In 1872, it was purchased by William C. and Sarah D. Kingsley. Kingsley, one of Brooklyn’s 19th century movers and shakers and a booster behind the Brooklyn Bridge, died in 1885, but the family owned the property until after Sarah’s death in 1913; it was finally sold at auction in 1916.

Other elements, such as the swag and garland ornamented mantel of the front parlor and the similarly patterned wall covering in the room beyond, suggest a Colonial Revival-inspired redecoration sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century. Art Deco-era bathrooms with brilliantly colored tile suggest yet another era of alteration.

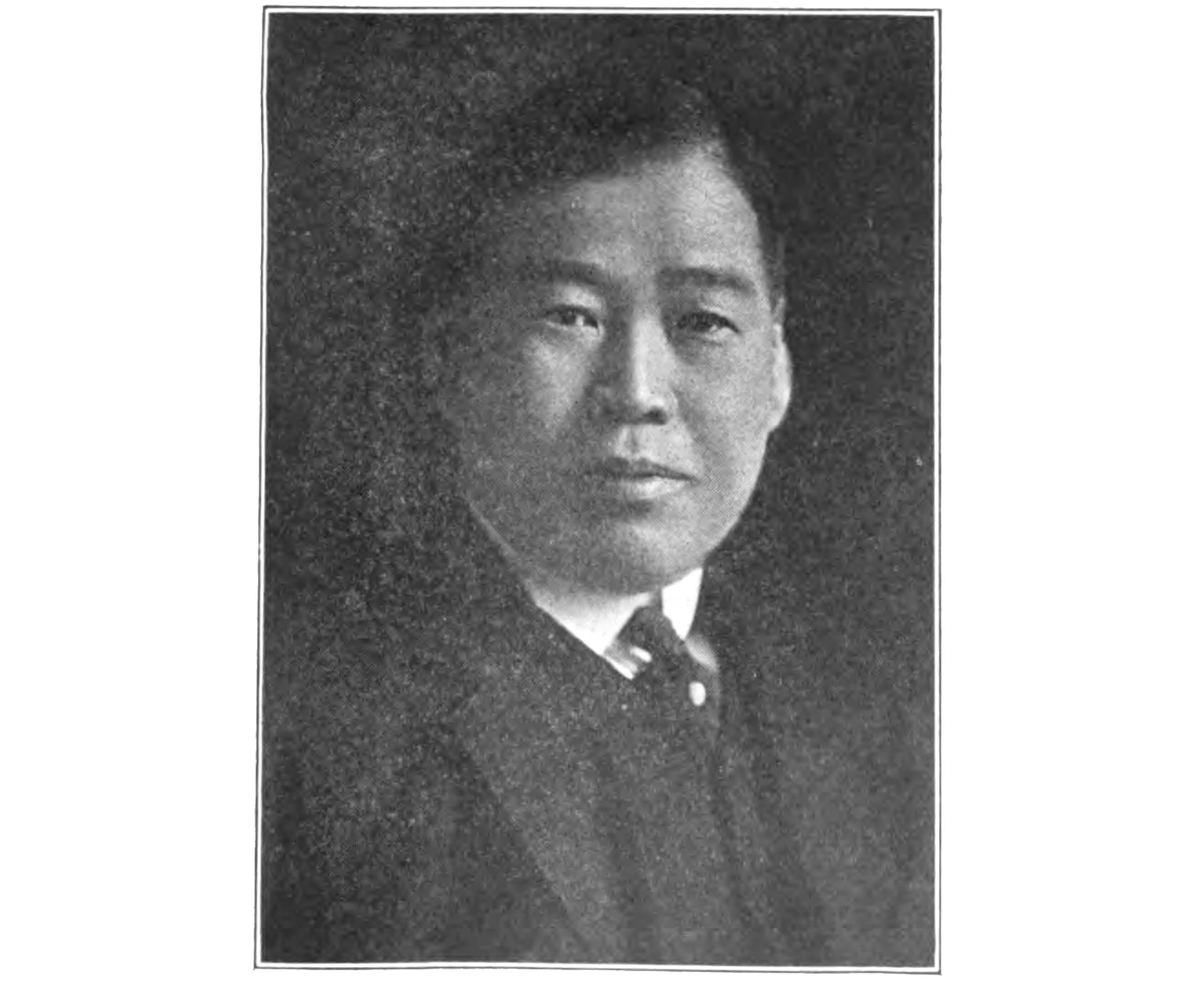

All of those could be changes made by the family who owned the house for the longest chunk of time over its over 150-year history. The purchaser at that 1916 auction of the property was Dr. Toyohiko Campbell Takami. After “extensive alterations” to the house, reported the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the Dr. Toyohiko Campbell and Sona Oguri Takami family would occupy the dwelling, “one of the finest in the Hill section.”

The purchase marked a significant step in the life of the family. The doctor had a rather extraordinary life’s journey. As a teenager he traveled hundreds of miles by foot from his home province of Kumamoto, Japan to reach Osaka and the chance to work his way aboard a ship to reach America.

He did so in 1891 and began work as a cook at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, learning English with the help of a mentor, Nancy E. Campbell, and working diligently towards his goal of an education in his new country. Among the schools he attended were the Lawrenceville School, where he was a member of the football team, and finally Cornell University Medical College, graduating in 1906. His autobiography, “The Shining Stars,” privately printed in 1945, is an engrossing read.

Married to Mount Holyhoke graduate Sona Oguri in Brooklyn Heights in 1909, Takami had staff appointments at several hospitals, including Bellevue and the Cumberland Hospital in Brooklyn. He was also active in the Japanese community in New York, forming the Japanese Mutual Aid Society, now the Japanese American Association, in 1907.

The move to the Washington Park manse gave the couple a grander home for their growing family and office space from which Dr. Takami could conduct his private practice. In an interview with historian and author Daniel H. Inouye, recounted in his 2018 book, “Distant Islands,” the Takamis’ daughter Mitsu Kurahra recalled her father having a waiting room for patients on one level of the Fort Greene house and on the floor above a large office with a specially designed planter, supported with steel, that had a stream of water flowing amidst the plantings.

The doctor’s waiting room was likely on the garden level, accessible from the street. The room at front has remnants of wainscotting and beyond it the space has been carved up into multiple rooms, some divided by glass-paned doors. A small room with built-in shelves and a sink are perhaps remnants of office use. The garden level was also the last somewhat habitable space in the building and where the last occupant of the house lived.

The upper levels of the house would have included the Takami family bedrooms. Six of the eight Takami children grew up in the house. The upstairs rooms again have remnants from the 19th and 20th centuries. There’s a bit of molding and some Italianate-style marble mantels. The original design of the floors and ceilings are barely discernible. One room has a floor a bit too treacherous to venture in safely for a closer look at the heavy wooden mantel.

The attic once held rooms for the household servants. Over the years of the Takami residence, they included cooks, maids and nurses. In 1920, the census shows, the household included two cooks and a servant, all born in Japan, in addition to the couple, their five children and Sona Takami’s mother. Daughter Mitsu also recalls a chauffeur driving her father, and there would have been room for a car in the garage at the rear of the property, with an entrance off Willoughby Avenue.

The house in Fort Green wasn’t the only home for the Takami family. They owned a summer home in Cold Springs Harbor that included an 1890s Queen Anne style house with plenty of room for entertaining. Now known as Olney House, the Takami family sold it to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1973.

According to author Daniel H. Inouye, Dr. Takami would have been an “elite” amongst the issei (Japanese immigrants to North America) of New York City. While not as wealthy as some, he had social prestige through his established medical career and a commitment to community service, serving on the board of multiple organizations and made possible the establishment of a Japanese burial ground at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Queens. Dr. Takami died in 1945, still the owner of the house on Washington Park. The family appears to have owned the house until at least the early 1960s; son Dr. Masahiko “Ralph” Takami had his medical office in the house in 1960.

In 1964 a deed shows that the house was acquired by John Tremmel. It transferred to Joseph Tremmel in 1970, making the Tremmel family the last of three families to own the house for significant periods.

How much detail can survive on the interior during the renovation remains to be seen. The house was without heat and electricity for years, water seeped in through the roof, and animals took up residence inside. Detailed plans for the house by Shape Capital and Kane Aud Architecture and Urban Design are still in development, but will include incorporating five condo units, one per floor in the main house and another in the garage.

“We want to respect the history of the house and include original elements,” Maysaa Halloway, a partner with Shape Capital, told Brownstoner during a tour of the house last month. Some details, such as the scrolled ornaments on the elegant stair stringer, survive relatively intact while elsewhere entire walls have lost their plaster and consist of broken lathe.

Also still in process are plans for the exterior. Historic images show that the exterior of the house was altered between 1958 and 1978, including removal of all of the original ornamentation on the front facade. The project will need to go through the Landmarks Preservation Commission review process.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Fort Greene Historic District Manse at Center of House Theft Case Now Listed as a Teardown

- The Japanese House in Prospect Park South

- A Brownstone for a Remarkable Woman, Brookyn’s Pioneering Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment