Dozens Debate If Apartment Tower Would Diminish Landmarked Fort Greene Church

More than 70 people testified at a Landmarks Preservation Commission hearing on a proposed 27-story tower planned for a landmarked Fort Greene church.

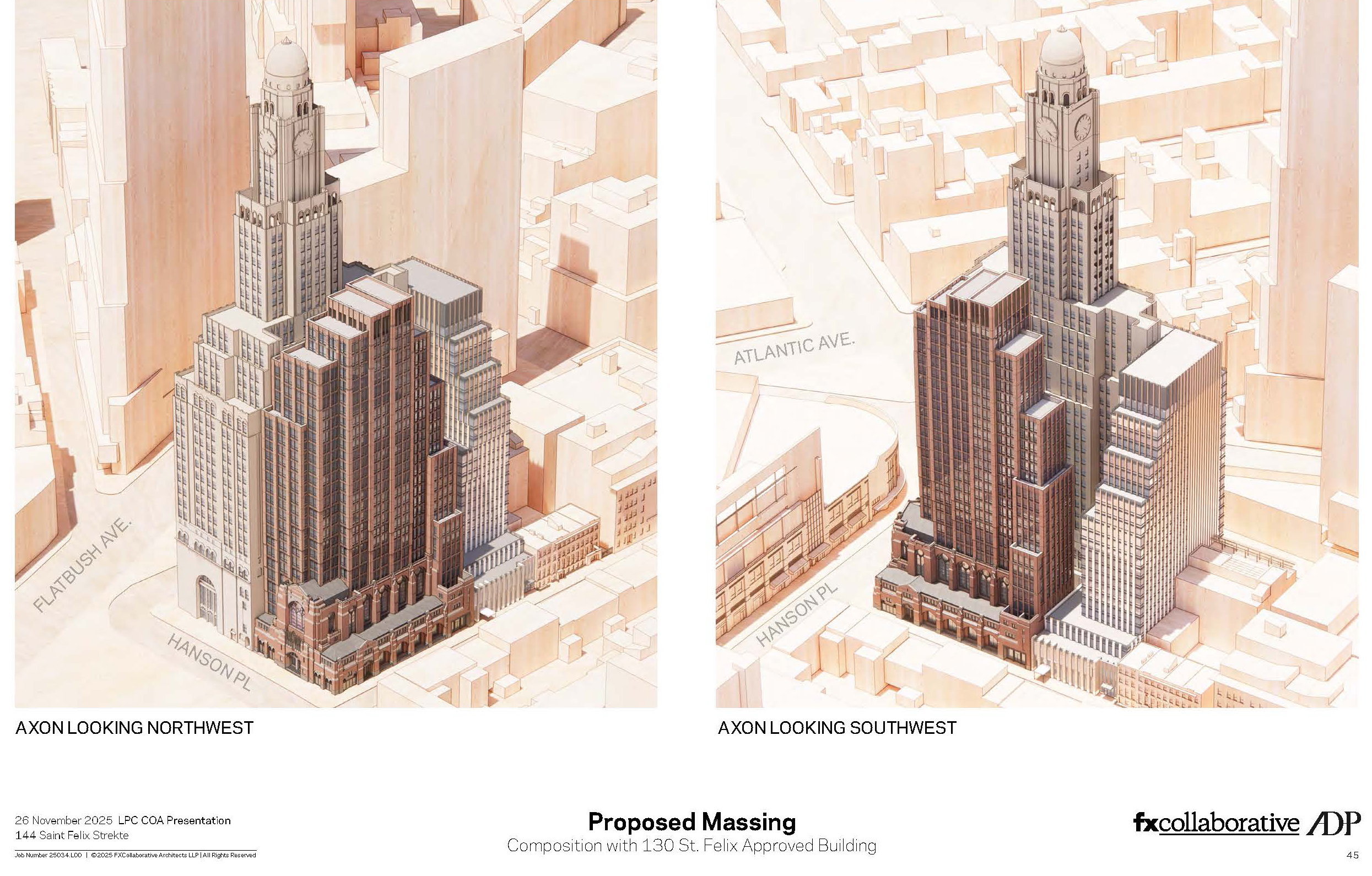

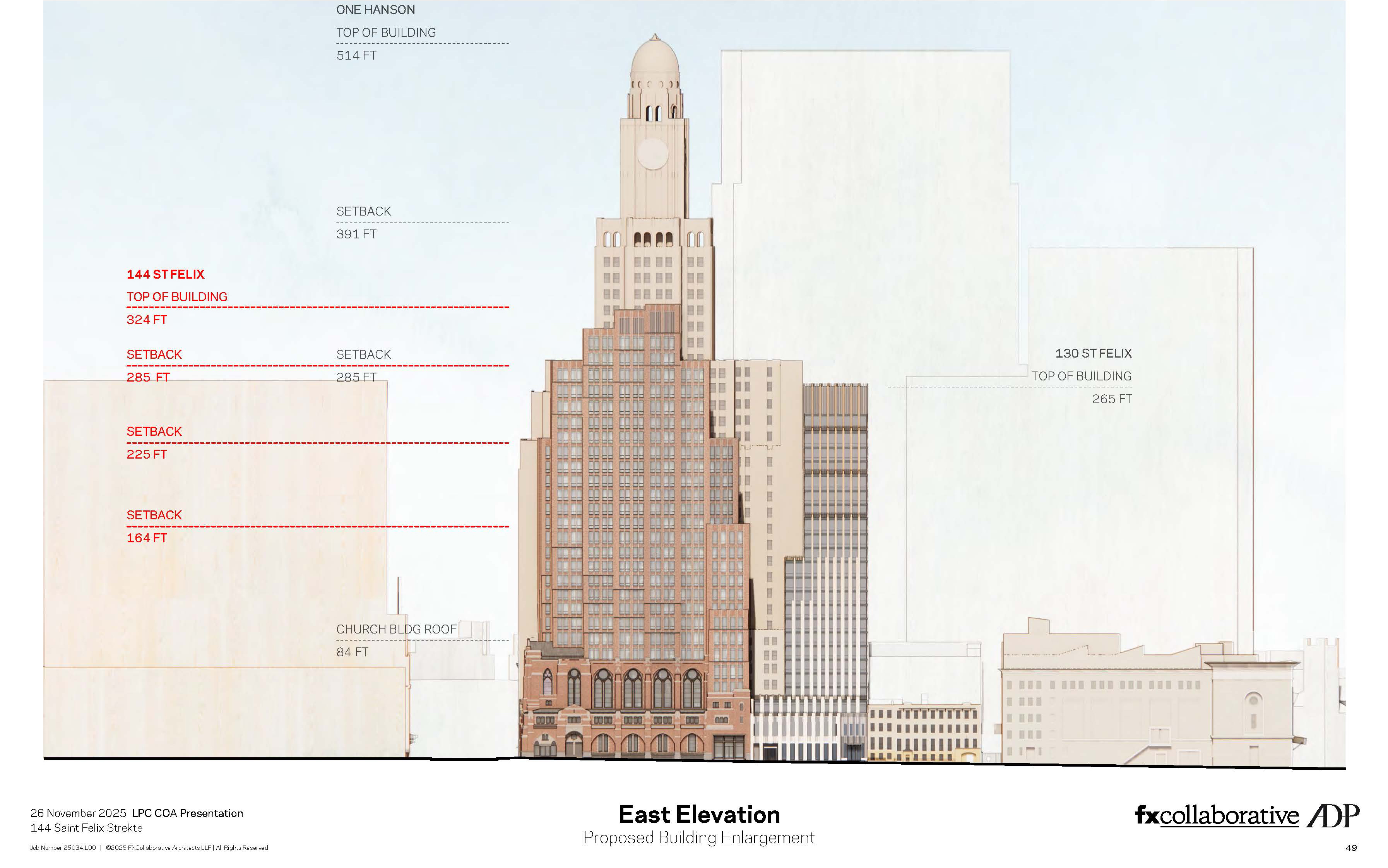

Rendering by FXCollaborative and ADP Architects via LPC

In a heated, 3.5-hour hearing, close to 80 speakers weighed in on whether the Landmarks Preservation Commission should allow a developer to build a 27-story, 240-unit tower using Fort Greene’s landmarked Hanson Place Central United Methodist Church as its base.

Forty-six speakers supported the plans for the church at 144 St. Felix Street, on the corner of Hanson Place, largely citing the need for new housing — and many said the design was respectful of the church, the neighboring Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower, and the BAM Historic District. But 33 opponents argued the project was grossly out of scale, would block views of the iconic clock tower, undermine the church’s history and architecture, and amount to “facadism.”

The commissioners received 95 letters opposing the plan, and 64 supporting it. During the hearing, LPC staff and several speakers reiterated that housing policy is not within the commission’s purview.

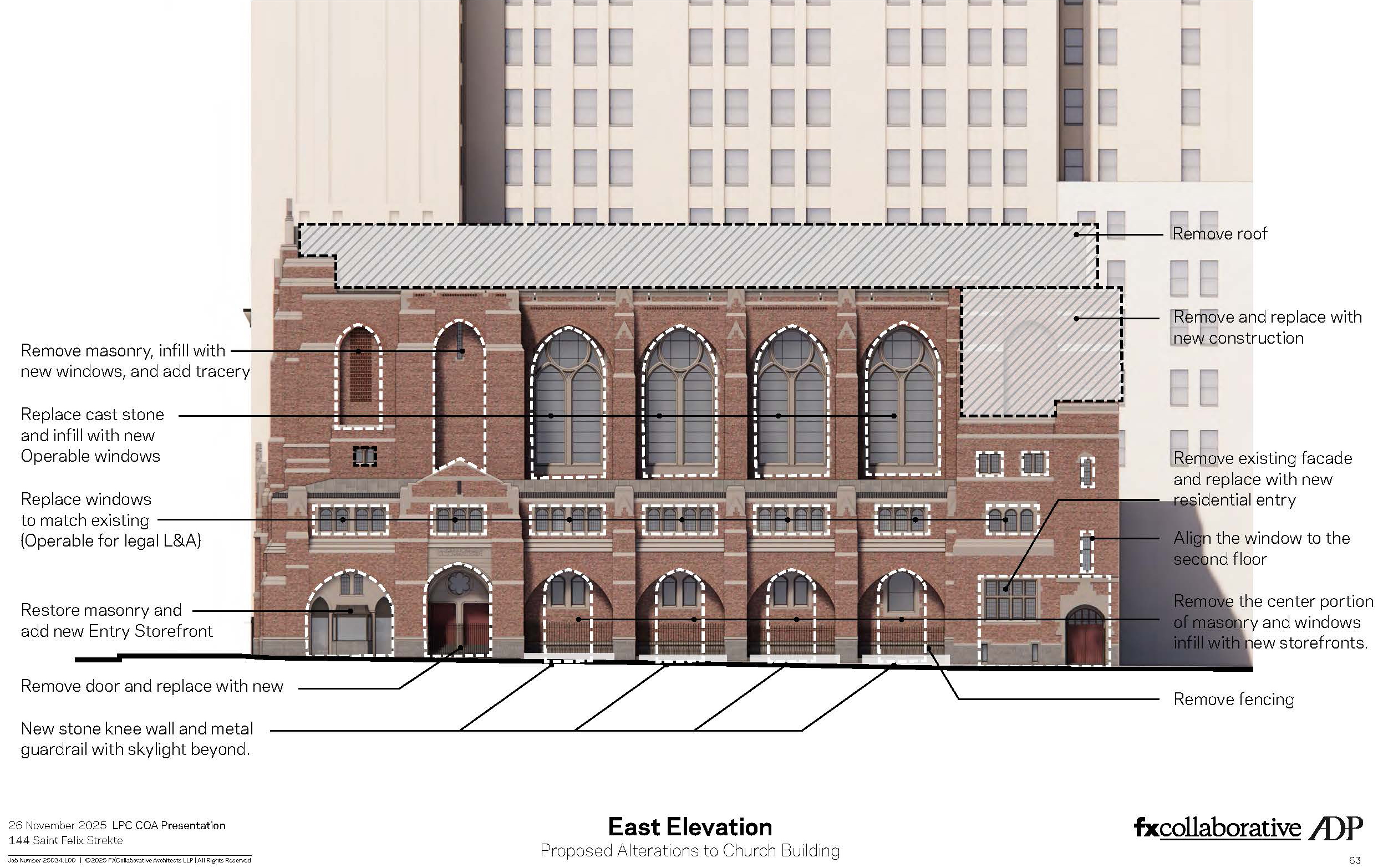

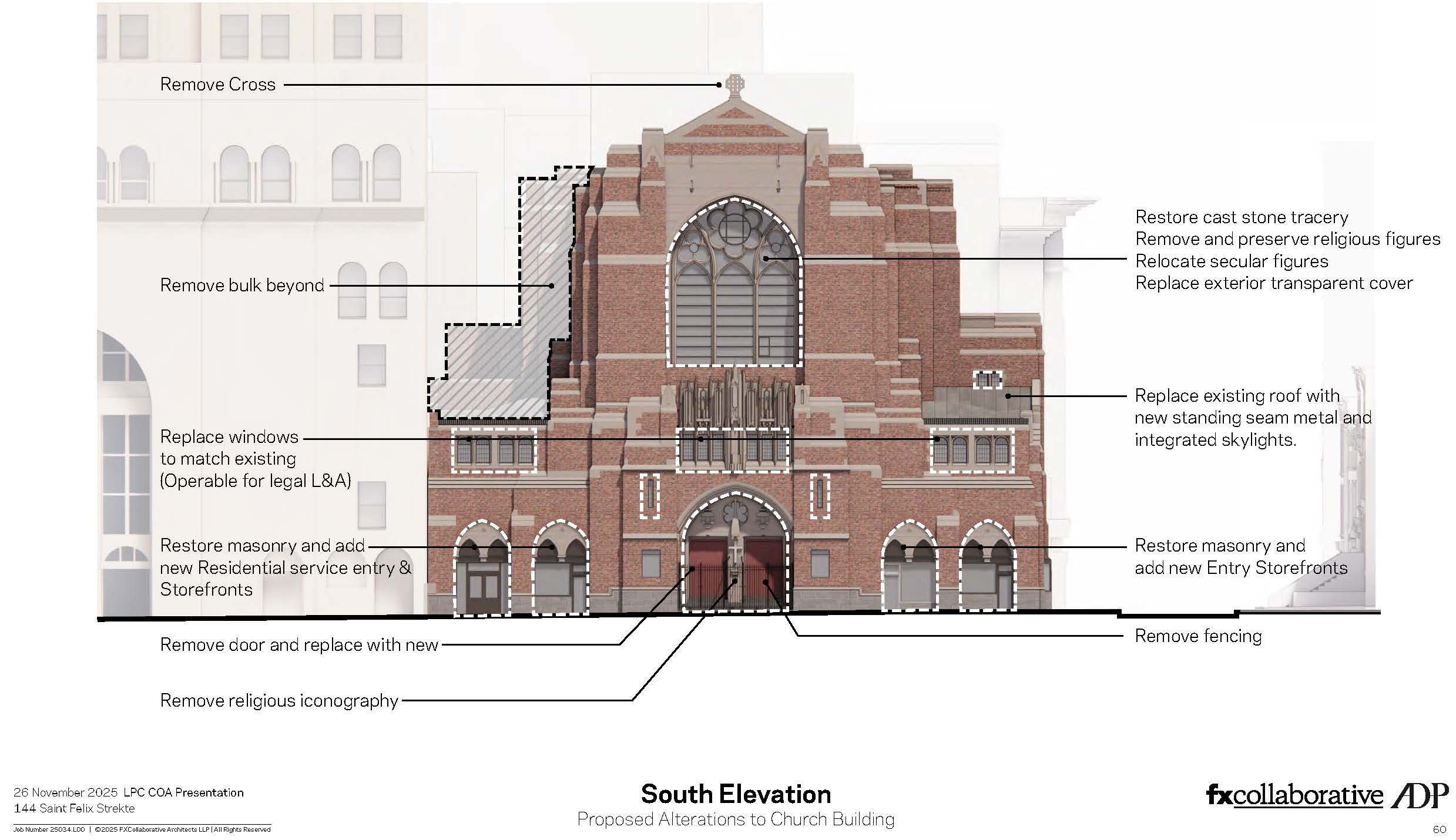

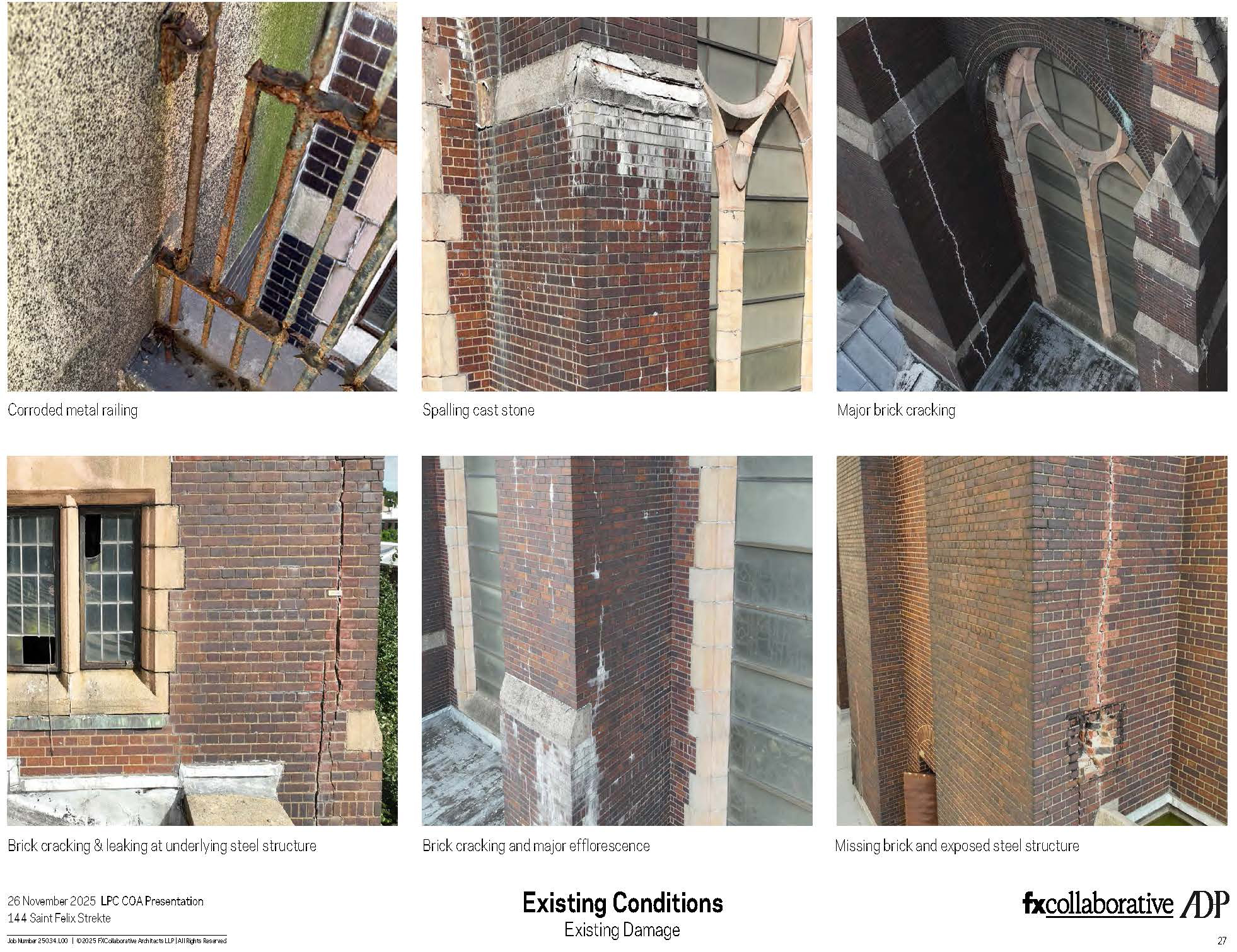

Developers Strekte have applied to alter the 1930s neo-Gothic church, designed by Halsey, McCormack & Helmer, by demolishing portions of the structure, removing and relocating doors and stained-glass windows, and constructing the tower. FXCollaborative and ADP Architects (the latter also behind the controversial proposed tower at the Duffield Street Houses) are designing the project, which requires LPC review because while the church is not individually landmarked it sits within the BAM Historic District.

The proposal includes restoring the church’s St. Felix Street and Hanson Place facades; repairing masonry and cast-stone ornamentation; restoring stained glass; removing and preserving religious iconography; replacing windows to meet light and air requirements; and adding new doors, skylights, a roof, and retail and community spaces. The attached 27-story brick-clad tower would step down along both streets and contain 50 to 60 permanently “affordable” — e.g. rent-stabilized and income-targeted — units.

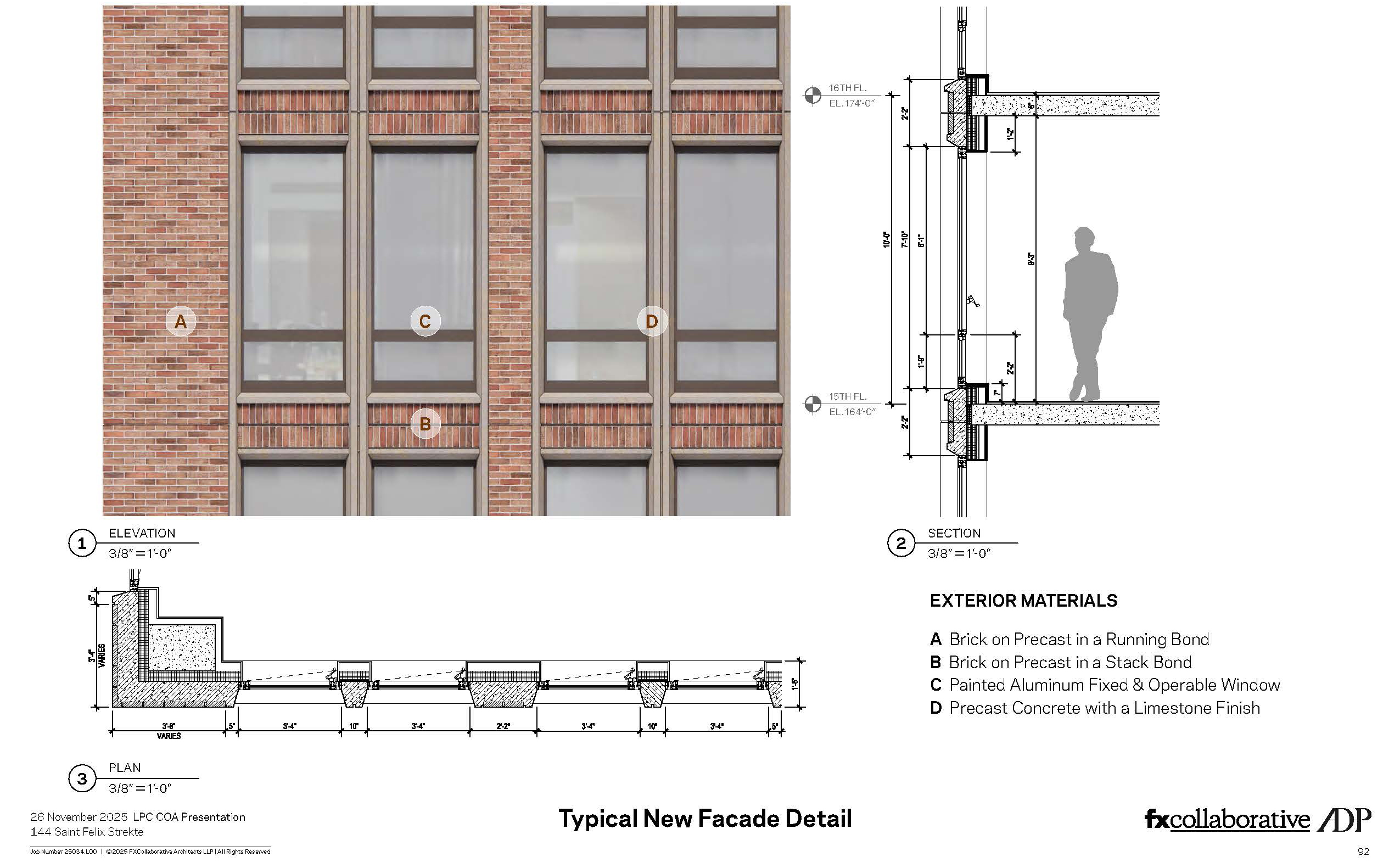

The design team said it would use neutral and highly transparent glass, the same brick it was using to restore the church but with tonal variation to complement it, limestone concrete to also match the existing structure, and bronze and warm-gray metal finishes.

Former LPC Chair Meenakshi Srinivasan of Cozen O’Connor Public Strategies presented the plans on behalf of the developer alongside FXCollaborative’s Dan Kaplan and Bill Chalkley and preservation consultant Drew Hartley of Acheson Doyle Partners Architects. She said the church had long been on the market and needed $25 to $30 million in restoration and stabilization work. “The proposed residential enlargement above the church will provide the investment and viability to restore and stabilize the church and at the same time provide much needed housing,” she said.

Kaplan said the design incorporated multiple setbacks to respond to One Hanson Place and the approved but not yet built tower at 130 St. Felix Street, as well as the surrounding historic district. The tower’s coloration, structural design, and fenestration were drawn from the church, he said, with it intended to look like it “grew out of the church.” Its stepped Art Deco massing was designed to relate to the district and the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower, until 15 years ago the tallest building in Brooklyn. The FXCollaborative team has worked on both plans for 130 St. Felix Street and the adaptive reuse of One Hanson.

“The design drivers are really three things,” he said. “Obviously, this wonderful church building in poor shape, how do we restore it? Second is the massing of the enlargement…and finally, make it relate to the historic district.”

He said the team’s three goals were “to enable the adaptive reuse of the church” in a primarily residential conversion while preserving as much of the historic fabric as possible, to “create something unique and complementary to this situation and, three, really make something that works with the historic district itself and its ethos and DNA.”

While LPC can’t consider housing in its decision making, most supporters focused on the number of apartments the tower would bring. Regina Myer of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership said the project’s 240 units, including affordable ones, would be well situated near transit and jobs, adding “residents of the new building will support local businesses and add to the vitality that makes Downtown Brooklyn a true 24/7 neighborhood.”

“This project finally provides a realistic path to restore and preserve a portion of the church in its exterior facade, bringing new life to a building that has been a blight on the neighborhood for far too long,” Myer said.

Joshua Levy said the proposal was a way to preserve the facade of the vacant building “with real care, while adding new housing our community truly needs. This is exactly the kind of creative, respectful development our neighborhood deserves, one that honors the past while building for the future.”

Others saw the church as a blight on the area that needed immediate attention. Retired NYPD officer Bobby McGinn said he had watched the site “slowly falling apart,” becoming “a magnet for crime.”

The redevelopment, he said, “preserves the character of the original church while providing much needed housing…This project will reduce crime, create jobs, and finally, bring stability to a location that has been neglected for far too long.”

Real estate broker Imrul Hassan, who said he had lived and worked in the BAM District, said the project was “not only appropriate for the district, it’s necessary for its continued vitality,” adding, “Preservation is not just about keeping old buildings, it’s about keeping them alive.”

Opponents, however, argued the church was far from an eyesore and said the new tower proposed to rise from it would overwhelm the historic structure, obscure the bank building (which was called a beacon and Brooklyn’s most iconic building by multiple speakers), and set a dangerous precedent. While a representative from Historic Districts Council, Mahnoor Fatima, said the restoration work was promising, she said the skyscraper atop the church was “incompatible with the historic scale, form, and character of the BAM district.”

Many residents of One Hanson spoke opposing the project, with a number saying it was demolition masked as preservation that used affordable housing as a red herring. Many said they did support adaptive reuse for truly affordable and contextual housing at the site.

Resident and board member at One Hanson Place Joseph Salvidio urged the commission not to rush and to consider alternatives, saying there was too much at stake and there were “smarter ways to bring affordable housing to our community.”

Karen Saah, also a One Hanson resident, compared the plan to the rejected Duffield Street proposal, saying “both of these proposals preserve only the facades of historic buildings, subordinating them to the large towers proposed to be built on top of them.”

“They lack any consideration of alternative design proposals and fail to answer the question of why these historic buildings cannot be appropriately preserved and 100 percent affordable or senior housing built at a much, much lower scale,” she said.

Jeremy Woodoff of the Victorian Society said “it looks as though the proposal came in the aftermath of an aerial bombardment or an earthquake,” while Andrea Goldwyn, of New York’s Landmarks Conservancy, said the proposal retained only two elevations of the church, raising concerns about structural survivability during construction. The tower’s scale, she said, “would overwhelm the remains of the church,” and she urged exploring adaptive reuse within the existing envelope.

Jesse Webster said the plan contrasted sharply with architect Robert Helmer’s original vision, which paired the Williamsburgh Savings Bank “soaring cathedral of thrift” with the low-rise church designed as its companion. He accused FXCollaborative of proposing to “demolish Helmer’s church…to erect a generic tower from what remains of essentially its carcass,” and said approving the plan would be “arbitrary and capricious.”

“Crucially, this proposal reveals a profound contradiction for the architects, because in 2020 LPC accepted Kaplan’s argument that the church’s low rise scale was necessary to make the Gotham development [at 130 St. Felix Street] appropriate for the district…now he’s coming back to argue the exact opposite,” he said.

Several speakers argued the project risked eroding historic district protections and undermined LPC’s role in safeguarding landmarks. Elizabeth Farone, who said she is a big supporter of affordable housing and had lived in a homeless shelter before finding affordable housing herself, said she supports affordable development, but “not at the expense of breaking protective laws and destroying irreplaceable beauty.” She said “the city seems to be wrongly behaving as agents for the developer” and warned that approving the plan would “shatter the hearts of those who appreciate” the neighborhood’s landscape.

Francoise Bollack of the City Club of New York said the proposal “would make a mockery” of landmark protections, calling it “a sad example of facadism.”

Following the hours of testimony, the hearing was closed and the commission took no action. LPC Chair Angie Master thanked the dozens who testified, noting the “tremendous outpouring” of public input. She said the commissioners and applicant needed time to “think about all the testimony that we heard” and the project would be brought back to the commission for discussion and a vote, although no time frame was provided.

Related Stories

- Locals Push Back on 27-Story Tower Planned for Historic Fort Greene Church

- Fort Greene Church Inks Deal for $15 Million Sale Next to Stalled Controversial Condo Tower Site

- Building of the Day: 1 Hanson Place

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment