Building of the Day: 3100 Atlantic Avenue

Brooklyn, one building at a time. Name: Arlington Village Address: 3100 Atlantic Avenue (catch-all address) Cross Streets: Atlantic, Liberty, Montauk Avenues, and Berriman Street Neighborhood: East New York Year Built: 1946-49 Architectural Style: Some buildings vaguely Dutch influenced Architect: Unknown Landmarked: No The story: Whenever I had wheels, when I lived in Central Brooklyn, I…

Brooklyn, one building at a time.

Name: Arlington Village

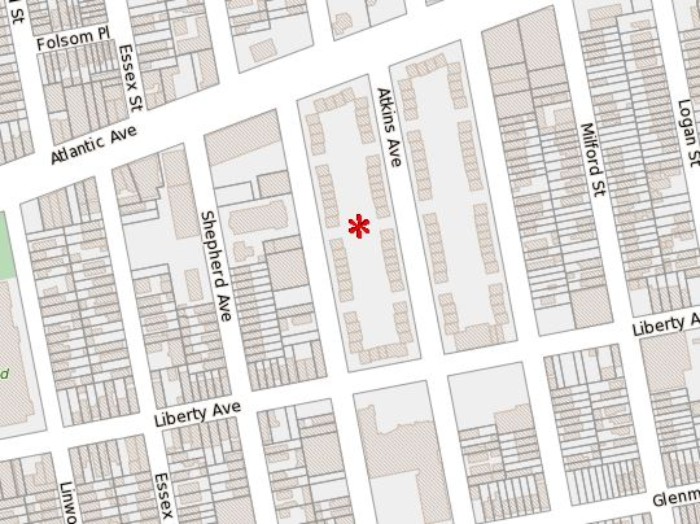

Address: 3100 Atlantic Avenue (catch-all address)

Cross Streets: Atlantic, Liberty, Montauk Avenues, and Berriman Street

Neighborhood: East New York

Year Built: 1946-49

Architectural Style: Some buildings vaguely Dutch influenced

Architect: Unknown

Landmarked: No

The story: Whenever I had wheels, when I lived in Central Brooklyn, I would make it out to the Costco on Rockaway Boulevard, in Queens, or sometimes go to the Gateway Mall in East New York. Both trips would take me far along Atlantic Avenue, and I’d always pass this complex, the side buildings of which face Atlantic Avenue. Like most people who live in New York City, I always thought they were public housing projects, perhaps a precursor of the tower projects that now fill so much of Brownsville and parts of East New York. Turns out I was right, but also wrong.

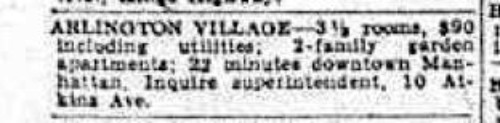

These buildings were called Arlington Village, and take up two square blocks, bordered by Atlantic Avenue, Liberty Avenue, Berriman Street and Montauk Avenue, with a partially closed off Atkins Avenue in the middle. They were built by the East New York Savings Bank as housing for returning World War II veterans and their families, and were built between 1946 and 1949. The complex has 107 buildings, which included 3.5, 4.5, and 5.5 room apartments, a diner, grocery store, off street parking and a children’s playground. The apartments all faced into the interior courtyards.

Public housing was a big concern for the city at the time. Returning vets from the war were by and large working class men with families who could not afford expensive housing. Many were taking advantage of the G.I. Bill, and were getting an education, also limiting their incomes. The rush to the suburbs of Long Island would soon start, but those who called Brooklyn home were offered inexpensive rents in apartments in developments like this, as a reward for duty to country. These developments were not offered to all of the war’s veterans, but that’s another story.

This one almost didn’t get off the ground. Four different savings banks were involved in this project initially: East New York Savings Bank, Hamburg Savings, Lincoln Savings and Prudential Savings Bank. The land they were seeking to build on had been zoned residential, but surrounding businesses on Atlantic Avenue had banded together to file suit in order to have the area zoned unspecified, which would enable them to do anything they wanted on their property. The banks told the city that they would have to back out, as it would be hard to rent to tenants with factories and noise nearby, and they would lose their investments. The businesses argued that they were there first, and they were being penalized from running their businesses or selling their land.

The land had been re-zoned residential in 1941, after the LIRR buried its tracks in that area of East New York, opening it up to residential development. The complex would be sitting on the site of an old rail yard. Representatives of the banks said they had no objections to a gas station or a store near the Village, but strongly objected to a factory or heavy industry. There were also a lot of other older houses in the neighborhood, and many also joined the suit, siding with the banks. Eventually, the banks won, and construction began.

The next problem surfaced when the independent contractor doing the plasterwork was hit up by mob extortionists who wanted kickbacks, or the project would not be completed. In 1949, as the second phase of the project was being built, the Brooklyn Eagle reported that mobsters claiming to represent a part of the plasterer’s union told the contractors to add $25,000 to their bid, earmarked for “taking care of a partner.” He refused, and contacted the authorities. The paper does not follow up, so I hope there is no one buried underneath Arlington Village.

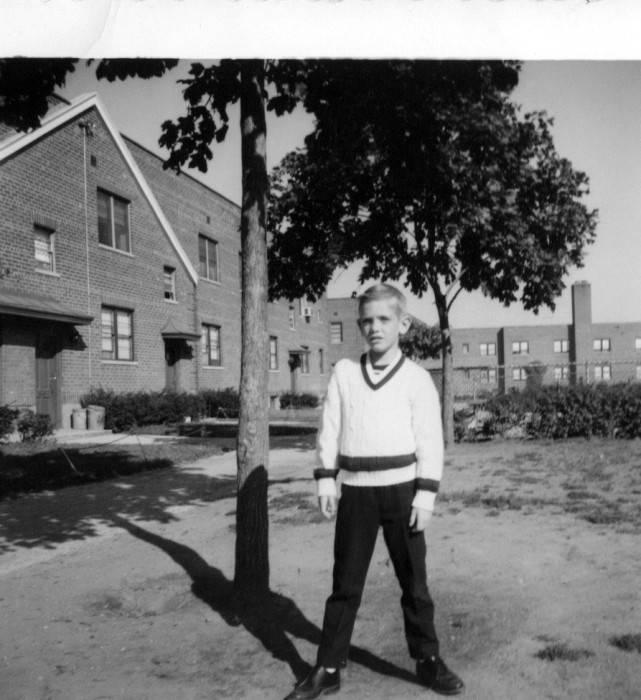

The entire complex of over 900 apartments was finally finished in 1949, and people soon filled it to capacity. Each block of buildings was a combination of the larger and smaller apartment units, creating diversity in family size, and the demographics of the families. While veterans were preferred, the complex did rent to others who met the rent and occupancy criteria. They were all only two stories high, and were much less oppressive than high rises, and the courtyard and grounds gave these modest apartments a nice garden-like atmosphere. The entrances all had metal roof hoods, the only detail in the complex.

In 1950, the complex’s superintendent, Mrs. Emily Bitterlich, was held up by four men who demanded the rent money, which had just been collected that day. One man had his hand in his pocket like he had a gun. Mrs. Bitterlich, who was a tough lady, told them she had deposited the money in the bank already, which was not true, it was in a drawer in the office. She offered the bandits her purse, with $20. They took her watch, valued at $75, and searched the office, but missed the money somehow. They then got lost getting out of the complex, and had to be shown the correct exit by Mrs. Bitterlich, who then called police. As stupid as they were, they were probably caught.

Eventually, the East New York Savings Bank and its partners sold Arlington Village, when it was no longer profitable for them to be in the housing business. The city bought it, and it became one of the many housing projects badly run by the city. By 2012, many of the buildings in the complex had been sealed, while others still had tenants. All of the metal hoods were long gone. The supermarket, last run by Key Food, had been one of the casualties, and was also sealed up. Meanwhile, a Bronx nonprofit called Picture the Homeless, which had received city funding, had a crash course in occupying empty city-owned properties. They chose Arlington Village as their testing ground.

One of their board members took their members to Arlington Village and told them how to break in and occupy the buildings. The theory was that if they stayed as squatters, registered to get utilities, and stuck it out, the city would eventually let them take over the building as tenants. They called it “homesteading.” Unfortunately, the “reclaimed” apartments were soon filled with drugs, pimps and prostitution. The legit residents of the Village were furious. It took the police and residents half a year to get the sex trade out of the complex, and the “homesteaders” out. The city was looking at Picture the Homeless for a lot of reasons, and was pulling their funding and filing criminal charges.

Google Maps photos taken in 2012 show half the complex boarded up. This is a shame and a crime. While I think Picture the Homeless had a point that the city was warehousing apartments, they had no right to “take them back.” But these buildings would not be difficult to rehab and re-introduce into the marketplace. Affordable housing is much needed, and these were decent places. Sell it to a private company, or Habitat for Humanity or another charity. People should be legally and safely living here. GMAP

(Photo:Nicholas Strini for PropertyShark)

I don’t know where the author of this story received his information regarding the Arlington Village, but this is not factual information. I lived here from 1976 to 2006 and the city NEVER owned this property. The owner of this property was an Austrian immigrant by the name of Fred Stark who owns Fred Stark Reality on Jamaica Avenue in Hollis Queens. Mr. Stark passed in the 90’s and his adopted daughter Rita Stark inherited the property and has not kept up with it since her father’s death. Rumors say she wants to keep this property for sentimental reasons. While others say that she is not keeping up with the property on purpose so that the tenants left can leave on their own and wont require a buyout from the Stark Estate, I personally believe that is the more likely of the two rumors. It is a shame that this place has gone to ruins. I grew up there and it was a wonderful place in the middle of the ghetto.

Great story. Every year or so we read news stories about NYCHA properties in bad disrepair/dilapidation but this one is never mentioned. Theres government subsidized affordable housing still being built on Flatlands ave. near the gateway center mall (South end of ENY) that is horrible to get to transit wise but yet this site thats a block from the J and 3 blocks from the A/C sits untouched, this seems like a really easy rehab. Maybe when realtors rebrand the neighborhood as East Bed-Wick Hills we will finally get some love.

Thanks so much for this. I wandered through these houses a few times when I worked out in East New York ten years ago and was always intrigued by them. They seemed a bit like projects but not like any projects that I have been to in NYC. Much sadder, really and more like projects in Baltimore or Camden. I even tried to do research on them but could never find any info. Thanks.