Building of the Day: 218 Gates Avenue

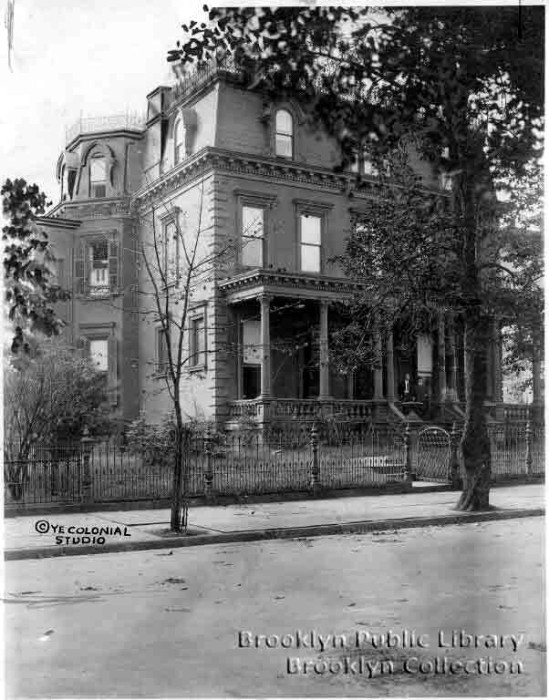

The Gibb Mansion is one of the great storied houses of Brooklyn.

Photo by Suzanne Spellen

Editor’s note: In honor of the 50-year anniversary of the Pratt Area Community Council, we are pleased to feature historic buildings PACC has redeveloped as our Building of the Day for four consecutive days. PACC is a community development corporation that preserves and develops affordable housing in central Brooklyn. Brownstoner is a proud media sponsor of PACC’s 50th Anniversary Gala, which takes place April 23.

Brooklyn, one building at a time.

Name: John Gibb Mansion

Address: 218 Gates Avenue

Cross Streets: Franklin and Classon Avenues

Neighborhood: Bedford Stuyvesant

Year Built: late 1860s

Architectural Style: Second Empire

Architect: Unknown. 2003 Exterior restoration – Kaitsen Woo. Additional housing and interior architecture by Beth Cooper Lawrence Architect PC.

Landmarked: No

The story: The Gibb Mansion is one of the great storied houses of Brooklyn. Built for a millionaire merchant, it remained in the news long after its original owners had died or family members moved elsewhere. The house went from fine mansion to hot pillow hotel over the course of its 150 plus year history, and could have met the wrecking ball a couple of times, but survived and is now thriving. Much of its history has involved helping those in need, so it’s fitting that its current incarnation is continuing this grand tradition. Here’s the story:

Scottish-born John Gibb was a very successful lace merchant, by 1865, a partner in the firm Wells & Gibb, in Manhattan. They were the largest importers and wholesalers of lace goods in New York, with a large warehouse on the corner of Broadway and Grand, in what is now Soho. Today that building now holds the International (formerly French) Culinary Institute of America, among other tenants. It’s a huge building, giving one an idea of the size and success of Gibb’s company.

Like many wealthy merchants, John Gibb lived in Brooklyn, away from the hustle and bustle of commerce, first living in Fort Greene, and then moving to a home he had commissioned, sometime after 1865. Gibb bought a great deal of land in Bedford, near the growing Clinton Hill neighborhood, and had his house built right in the middle of it. For many years after the house was built, there were no buildings between the mansion and Classon Avenue. John Gibb did not want to be crowded. Or bothered, but that comes later.

The Gibb mansion is a very large Second Empire brick house, with a mansard roof and a grand front porch. The house has several bays and rear extensions, and in his day had a grand parlor and receiving rooms, a large dining room in the rear extension, two bathrooms, and plenty of bedrooms. The Gibb family needed all the room they could get, as John and his first wife Harriet had eleven children. Harriet died in 1878, her funeral taking place in the house. Four years later, John Gibb remarried, and his second wife, Sarah bore him two more children.

The entire family would join Brooklyn’s social elite, and the elder Gibbs was active in Republican politics, and was appointed Commissioner of Parks under Brooklyn Mayor Seth Low in 1889. Gibb was well liked, but he could be a curmudgeon, too. He vehemently opposed the NY & NJ Telephone company’s plans to put up telephone lines along Classon Avenue, between Quincy and Monroe, which he owned. He even sued, and was successful in preventing the lines from going up. He groused that the lines prevented him from “the quiet enjoyment of his property.”

When not in Brooklyn, the Gibb family also had a second estate called “Afterglow” in Islip, where they spend their summers. There, John Gibb enjoyed his horses, sailed his yacht, the Bonnie Doone, and belonged to the local Penataquit-Corinthian Yacht Club. In 1887, Gibb and two of his eldest sons, Howard and Arthur, went into partnership with Frederick Loeser, who had a successful dry goods store on Fulton Street. He was one of their better lace customers. The Gibb men and Loeser turned the store in to Frederick Loeser & Company, one of the finest and largest department stores in Brooklyn, with a massive one-block square store on Fulton Street. That building still stands today, although much altered from its original appearance.

Gates more or less retired in the early 1900’s, leaving the businesses to four of his seven sons. He spent most of his time in Islip after retiring, sailing and riding horses. In 1901, the house at 218 Gates was on the market, advertised in the Eagle for sale for $13,000. In comparison, most of the houses in the area were selling for around $4,500. The house had several moneyed family owners after that, for a few years before World War I, but was too much house for most people to deal with. Besides, much of Brooklyn’s money was then moving to the suburbs or to swanky new apartments on Park Avenue.

Like many large houses, the Gibb mansion became a convalescent home. After the war, in 1919, it became the National League for Women’s Service Association’s Convalescent Home for Wounded Soldiers. 25 patients lived here and were cared for by the Association and its staff. They were only here for about two years, because in 1922, the house was home to the Long Island Motor Club, an upscale social club. The papers report their balls, meetings and outings, but they only stayed here a year or so, as well, as their members probably joining the exodus to the city or burbs.

Between 1923 and at least 1946, 218 Gates Avenue was the Hopewell House, the headquarters of the Hopewell Society of Brooklyn, a well-established and highly regarded charity that cared for underprivileged women, children and babies. The charity was a popular one among Brooklyn’s moneyed set, and the papers report many events and fund-raising drives that took place here. The house was home to a number of children, and walk-in care to poor mothers was also given here.

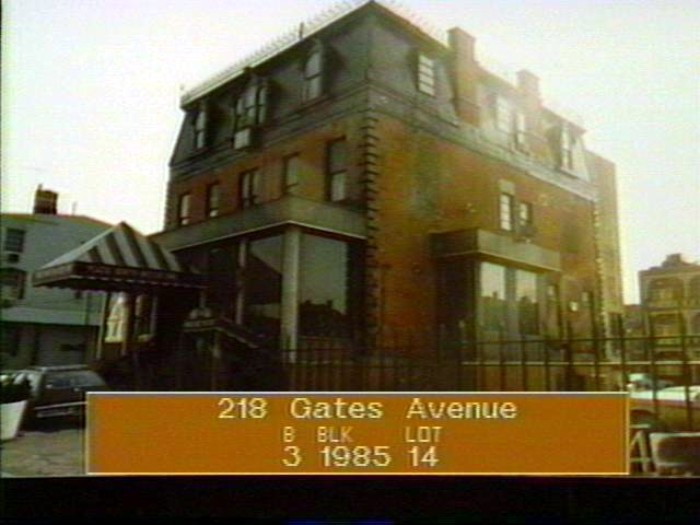

I did not find any newspaper accounts of Hopewell House after 1946. At some point, they left, and a large gap fills the time period between then abd 1965, when the house became the Plaza North Hotel, advertised as an events space, with a dining room and grand ballroom for weddings, social events and meetings. It was owned by James Cuffee, an African American businessman who sank $300,000 into purchasing and renovating the mansion. He received Brooklyn’s Businessman of the Year award for his efforts. He also owned several other establishments. The mansion’s ballroom and dining room were lavishly decorated and gilded out, and the Plaza North was a popular destination for weddings, and other social and dinner events in the Bedford Stuyvesant community during the 60s and 70s.

But by the late 1970s, it had started to deteriorate and get tacky. The gilt was off the rose, and the venue became known more for hot assignations, robberies and other felonious activity, not weddings and bridal showers. The building was lost to the City in 1973, but remained open for years, as NYC had no money and no desire to operate a building in Bed Stuy. In 1973, several robberies took place here which resulted in the incarceration of Sonny Carson, a local black activist. He was one of eight men indicted for hunting down and killing one of the men who robbed the hotel.

The tax photo from the early 1980s shows the house with its grand porch and side bays glassed in. I remember passing the place on my bus ride to work in Clinton Hill. The lights were always blazing, and the décor, as seen through the windows, was over the top bordello. There were also several out buildings out back and next door, that belonged to the property, and everyone knew that the hotel and especially the motel-style buildings out back were being used for prostitution. But eventually, even that ceased, and the building lay empty and neglected.

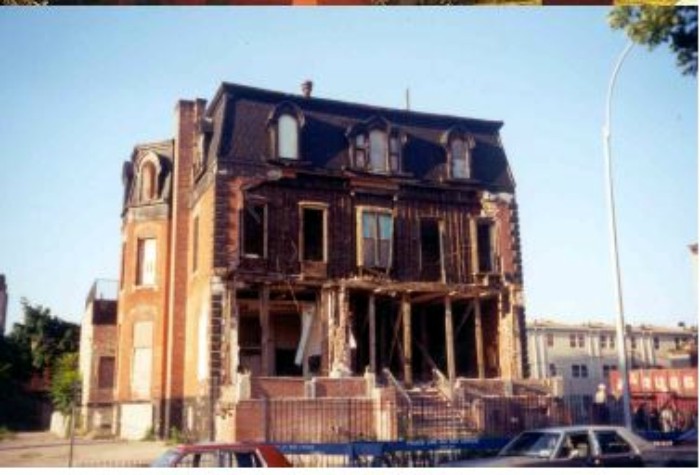

Brooklyn was becoming noticed by then, if not by upscale folk, then by developers who were quickly filling empty lots in Bed Stuy and Clinton Hill with infill “Fedders” housing. This huge plot must have looked like candy, and it didn’t look as if the house would survive. Good thing PACC came along. The Pratt Area Community Council bought the house from the city in 2000, and embarked on an ambitious program to restore the building, and provide housing for formerly homeless individuals.

Beginning in 2002, they tore down the motels and built new housing with studio apartments on the Monroe Street side of the lot. The mansion itself was redone, inside and out. The front porch was pulled down and restored, as was the interior, which now holds offices, meeting rooms and public spaces. The exterior restoration was designed by architect Kaitsen Woo. The interior and other architectural work, including the additional housing was done by Beth Cooper Lawrence, Architect.

Today, the Gibb Mansion complex has 72 units of housing: 50 affordable studio apartments for the formerly homeless and those with former substance abuse problems, and 21 units of housing for low income local residents. The Mansion provides 24 hour security, a library, computer lab, fitness center, therapeutic services, art classes, a dining facility and a recreation center. In 2003, PACC was awarded several awards including an award for “Outstanding Achievement” from the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce for the project, and in 2005, an “Excellence in Preservation” award from the Preservation League of New York State. The Gibb Mansion is the jewel in PACC’s crown. GMAP

(Photo:S.Spellen)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment