The Hecla Iron Works Factory Rose From the Ashes in Williamsburg

The company headquarters had offices, design and drafting studios, and a showroom that took up an entire floor.

Editor’s note: This story originally ran in 2013 and has been updated. You can read the previous post here.

The Hecla Iron Works was named after Mount Hekla, an active volcano in Iceland. A fitting name for a design studio and foundry established by two Scandinavians: Danish-born Niels Poulson and his Norwegian partner, Charles Eger.

The two men came to the United States at different times in the 1860s, and founded their business in a small office in Williamsburg in 1876, a boom time for building in Brooklyn and New York City. Both men had backgrounds as mason-journeymen, and Poulson had been an architectural draftsman in Washington DC, and architect/engineer for the Architectural Ironworks of New York.

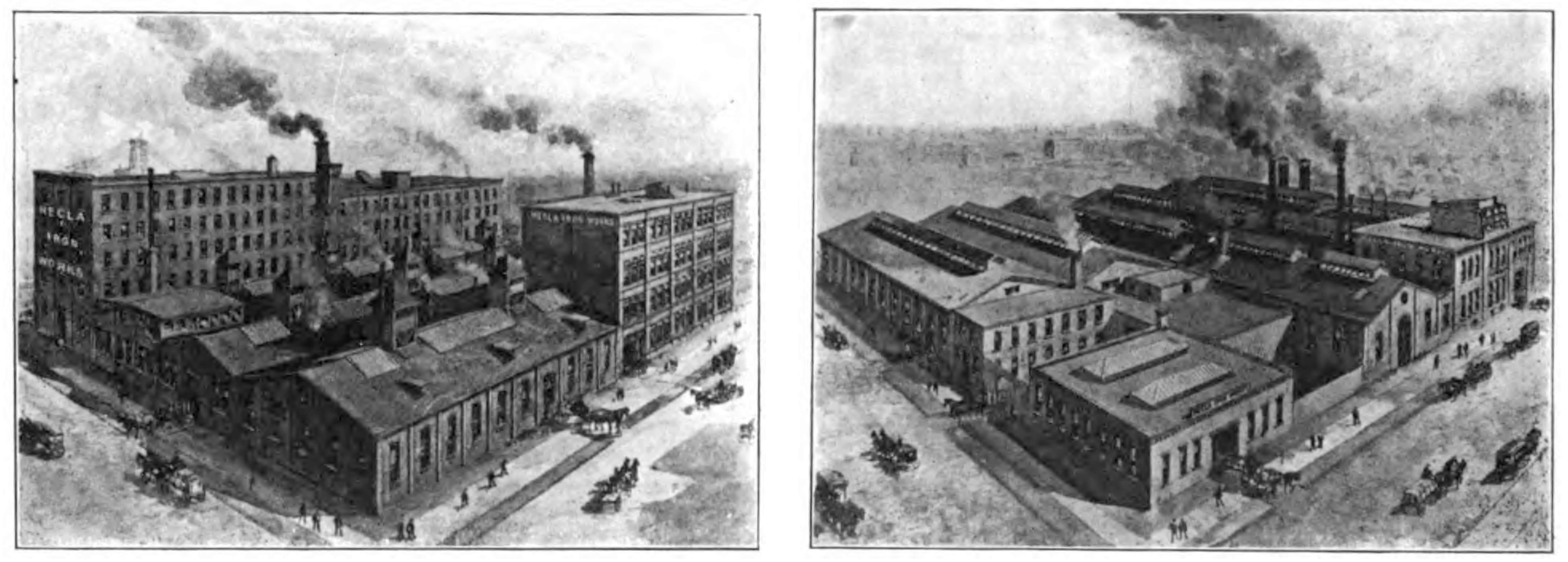

By the end of the 1880s, the Hecla Iron Works had grown to a large complex that took up most of the block between 10th and 11th Streets, Wythe and Berry in Williamsburg. Illustrations and photographs of that time show a busy, sprawling mass of buildings, with single story foundry buildings and multi-story office, warehouse, work and design spaces.

Most of this complex burned to the ground in 1889, and the remaining office building followed it, in a fire in 1891. The partners’ loss was over half a million dollars.

Undeterred, Niels Poulson began experimenting with fireproof design. He built himself a fireproof house in Fort Hamilton (now gone) using an innovative combination of non-combustible materials, including fireproof brick, plaster, and iron. This experiment gave rise to a new factory which rose on the ashes of the old, beginning in the 1890s.

In 1896, construction began on the last building in the complex at 110-118 North 11th Street. It was designed as the company headquarters, with offices, design and drafting studios, and a showroom that took up an entire floor. Inside the building, the floors were supported by a metal framework that vaulted up and was covered by vaulted plaster ceilings. The vaulted shape allowed concrete floors to be poured, their weight distributed by the vaults.

Industrial facilities of all kinds of important industries come and go in Williamsburg, as the vanishing industrial landscape gives way to residential building, and very little of it is landmarked. What sets the Hecla office building apart, and made it special enough to be landmarked in 2004, was also a feature that helped sell their products — the distinctive metal sheathing on the façade on the 11th Street side.

The cast iron fronted buildings that define SoHo, the Ladies Mile and parts of Lower Manhattan, as well as parts of Williamsburg itself, were relatively passé by the time Hecla built this building, but they used iron in a way that had not been seen before, with four kinds of cast iron, front and back, and glass and steel framed windows, used here, not to mimic stone, or suggest structure, but to form a metal skin, the forerunner of the modern curtain wall found in modern 20th century architecture.

They also used a new patination, the Bower-Barff process, which involved exposing the iron element to super-heated steam that converts the rust to magnetite, forming an impervious surface that needs no painting, giving the metal a soft, black velvety surface that has held up well for over one hundred years.

Hecla was one of only four firms in the United States licensed to use the Bower-Barff patented process. They not only used it in structural forms such as in the pillars, columns and ornament on this building, but they were able to incorporate it into the firm’s bread and butter — architectural ornamentation, including fencing, gates, cornices, decorative ironwork, statues, stairs, elevator cars and lighting.

Many of New York’s most iconic and familiar buildings have Hecla ornamentation, as do buildings all across the country. The fence around the Dakota apartment building is by Hecla, as is the Macomb Dam Bridge at 155th Street, the iron balcony and other ironwork in the 14th Regiment Armory in Park Slope, elevators and grillwork at the NY Life Insurance Building, the ironwork and elevators at the old B. Altman Store on 34th Street, ironwork in and on the NY Stock Exchange, the St. Regis Hotel, Grand Central Station and J. P Morgan Co.

They also produced the ironwork in 133 of the original kiosks for the IRT subway.

In 1913, Hecla merged with the Winslow Brothers of Chicago, a rival firm. The new company was called Hecla-Winslow. Poulson and Eger retired as rich men, and both men left sizable estates to their families and Scandinavian charitable causes. But the decline of the industry could be felt by the 1920s.

Poulson left the ownership of the building to the American-Scandinavian Foundation, which sold the building to the Carl H. Schultz Mineral Water Company, a division of the American Beverage Company, in 1928. Faded lettering still on the building advertised products from their line.

Architect Francisco Jacobus made some alterations to the rear façade of the building at that time. Since then, the ground floor of the building has been significantly altered, with the windows filled in and painted, with crossed bars forming an “X” covering the first floor, along with a roll-down gate and loading bay. In 1989, the upper floors of the building were converted to residential space. In spite of alterations, the building, as a unique structure in of itself, and as part of Brooklyn’s important legacy of industry and industrial spaces, was landmarked in 2004.

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- The Concrete Clock Tower of Robert Gair, an Iconic Dumbo Building

- The Slow Decay of a 19th Century Grain Storehouse in Red Hook

- Developing Consumer’s Park Brewery: The Fleeting Spice of Life

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment