Two Skinny Brownstones: The Narrow Houses of Fort Greene's Cumberland Street

People become successful housing developers by getting the most out of a piece of property, and Thomas H. Brush understood this well.

Editor’s Note: This post originally ran in 2010 and has been updated. You can read the previous post here.

People become successful housing developers by getting the most out of a piece of property. Thomas H. Brush, who was the owner, architect and builder of two narrow brownstones at 259 and 261 Cumberland Street in Fort Greene, and many other houses in Brooklyn, understood this well.

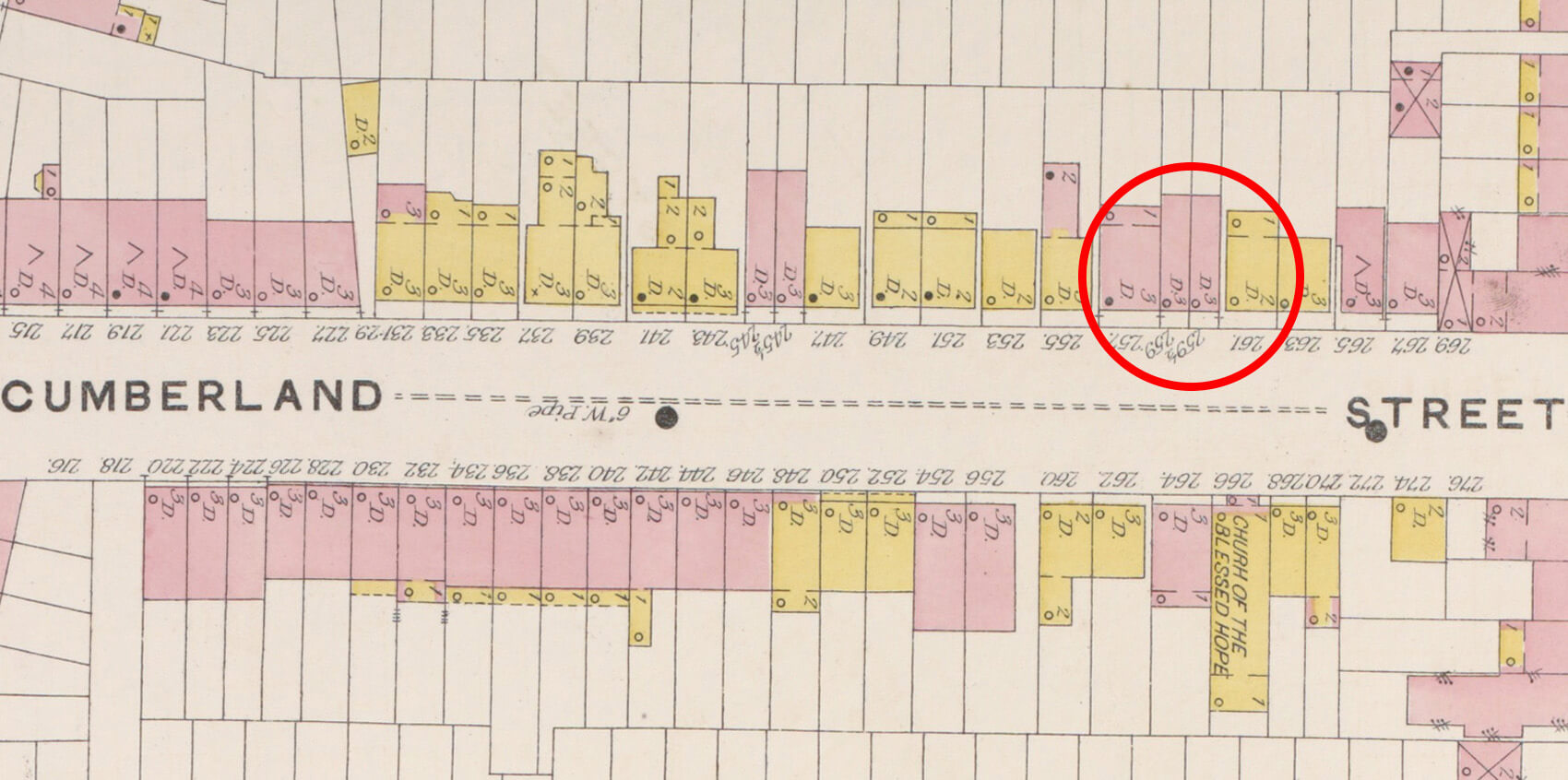

He was in possession of a 25-foot-wide lot on Cumberland Street between Dekalb and Lafayette Avenue in 1875, when Fort Greene was in the middle of a great building boom. He could have built a handsome 25-foot-wide mansion on this plot. It would not have been remarkable here, but he chose differently. He built two 12.5-foot-wide brownstones instead.

Acting as his own architect, and possessing a fine sense of balance and proportion, he divided the property in two. He designed them to look like one large house by placing the doorways on opposite sides, allowing an unrelieved bank of windows on the upper stories and a shared cornice to give the illusion of much larger homes.

He gave his 1876 transitional Italianate/Neo-Grec houses wide brownstone shelves and lintels, and framed the doors and windows with heavy molded sills. The eye carries upward, and then across, absorbing the illusion of one big house that just happens to have two doorways.

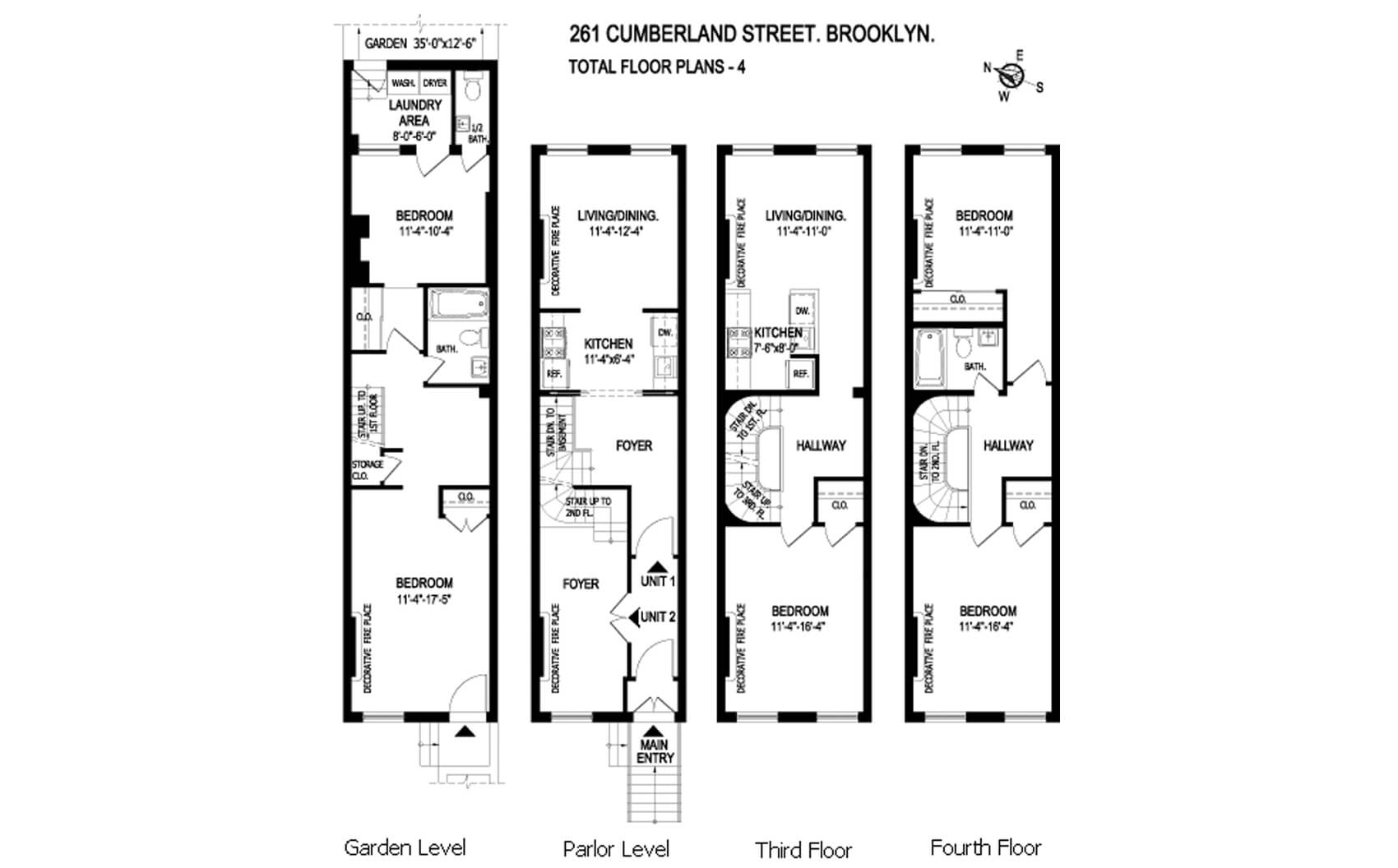

But in reality, the houses are among the narrowest in Brooklyn. They each have a center staircase, maximizing the floor space in the front and back rooms. No. 261 was last on the market in 2012 and there are still photographs of the interior on the Corcoran website, showing the layout of the rooms and a floor plan.

Life in a narrow house requires some getting used to, although it didn’t faze the Victorians. The residents here probably stuffed their large furniture and low hanging paintings and lots of drapery in the houses anyway.

When Miss Mattie Towers died in 1897, her funeral was held in her home at 259 Cumberland. That was probably a crowded affair. Miss Towers probably had a nice parlor window view, with the mourners gathered from the front parlor to the back of the house.

The family of Edward Ostrom lived for many years in No. 261, beginning around 1901. They were well-off enough for the son’s wedding to make the society pages of the Eagle and the Brooklyn Life society pages.

Edward Ostrom was many things, during his life. His father had been a prominent Brooklyn banker. He was one of the first members of Company C of the elite 23rd Regiment.

He taught a bible class for young men for 50 years in his capacity as the superintendent of the Mayflower Mission, part of the ministry of Plymouth Church.

He was also a professional curmudgeon. He was one of those people who were always writing to the newspapers complaining about something.

He wrote to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1903 complaining that the coal chutes in the new post office downtown on Washington Street were too small. When coal was delivered, the wagons took forever to empty because the men couldn’t get that much coal down the chutes at one time. Consequently, there were huge traffic jams on Washington Street whenever coal was delivered.

Amazingly, Ostrom received a letter from the postmaster stating this would be fixed and larger coal chutes would be installed, thanks to his complaint.

Emboldened by his new power, Ostrom took on his next target, one closer to his heart: Christianity. In 1907, the Board of Education had received many complaints by non-Christians about school celebrations of Christmas. They wanted to eliminate children being forced to sing religious carols in class and assemblies.

The Board of Education was considering it, as it was a clear separation of church and state issue. Ostrom was one of many members of the public who were incensed that a religious Christmas would be banned from schools.

He wrote in and complained, as did many others, both pro and con on the issue. Who said there was anything new under the sun?

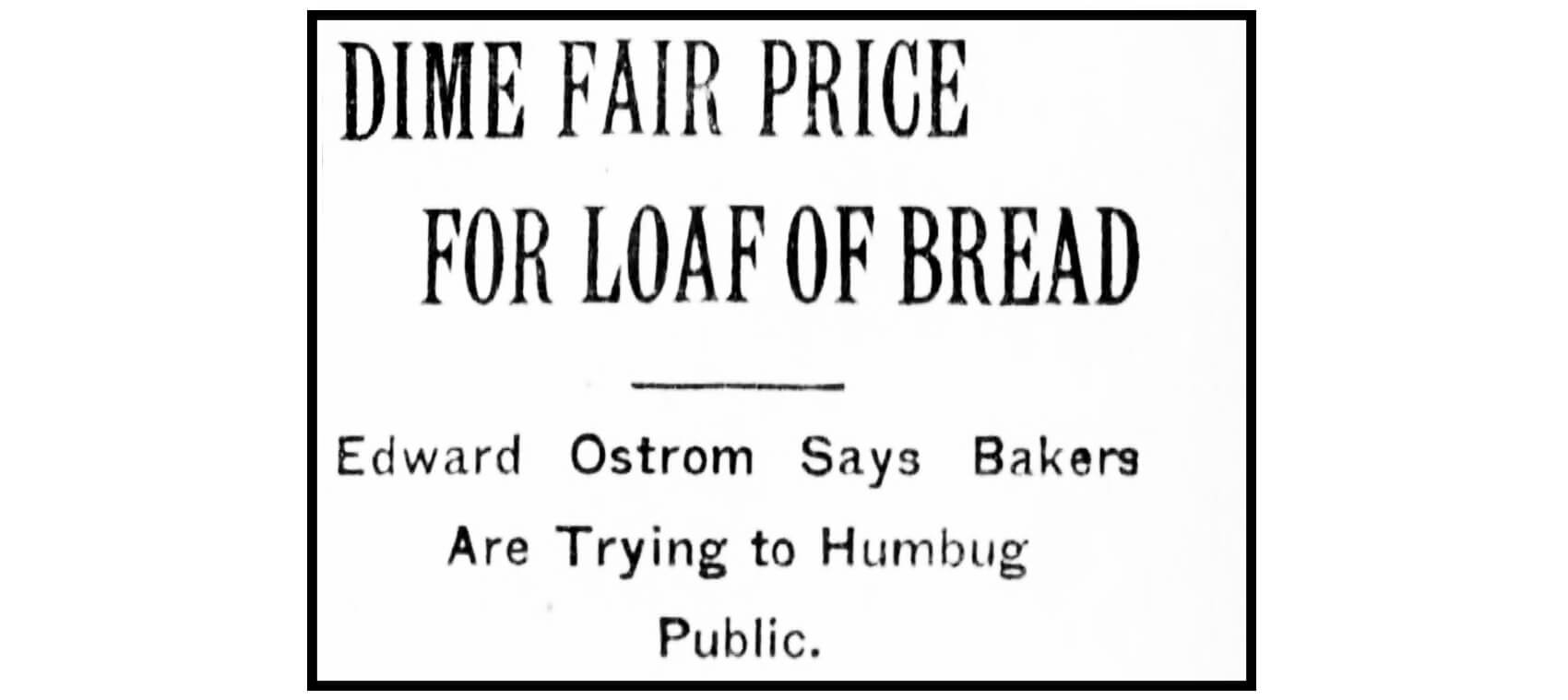

Finally, in 1917, he opined once more to the Eagle, complaining about the ingredients bakers were putting into bread. He accused bakers of pulling off a massive “humbug” on the public.

He noted that flour rose in part because of the gluten in the flour. The more gluten, the more the loaf reacted to the yeast, and the higher and fluffier it rose. He accused bakers of taking advantage of World War I shortages and war programs and cheating the consumer by not using more gluten.

He said that the humbug came when bakers protested that they could not sell a loaf for 10 cents, as had been the wont, because of the war. In actuality, he said, they were instead making huge profits by passing all of their higher costs onto the consumer. He wanted it stopped. He did have a point.

Unfortunately, his complaining days ended in 1923, when he died at the age of 76. Good or bad, Mr. Ostrom’s work continues. Letters to the editor are still extremely popular. He would have loved the comment sections on newspapers and blogs.

Related Stories

- House of the Day: 261 Cumberland Street

- Building of the Day: 293-299 Cumberland Street, a Greek Revival Row

- A Modest Monument to Education: P.S. 9 in Prospect Heights

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment