Walkabout: The Throop Avenue Church Disaster, Part 3

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story. In the early morning of January 9, 1895, a fierce windstorm rushed down the Hudson Valley and vented its fury on New York City. Gale force winds knocked down trees and power lines, and blew away anything that was not secured. Out on Fire Island, the…

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story.

In the early morning of January 9, 1895, a fierce windstorm rushed down the Hudson Valley and vented its fury on New York City. Gale force winds knocked down trees and power lines, and blew away anything that was not secured.

Out on Fire Island, the roof was torn right off a hotel. In Brooklyn two buildings came crashing down. One was in East New York; a theater that was in construction on the corner of Atlantic and Alabama Avenues. The wind cyclone around the walls of the building and knocked them down.

One wall fell onto Atlantic Avenue, the other on top of a house. The occupants of the house were injured, but no one was killed. On the edge of the Eastern District, on the corner of Willoughby and Throop Avenues, a similar scene played out. But in this case, two people died.

The walls of the Throop Avenue Presbyterian Church had reached their final height, and the builders would have put the roof on the building next. The storm destroyed that timeline as it devastated a family and a community.

The story of the church and the storm were told in Part One and Part Two. When the rear wall of the church crashed through the wood framed home of Mrs. Sarah Mott, it not only destroyed the house, but took the lives of her two grandchildren, 18 year old Mary Purdy, and 14 year old David Purdy.

The day after the disaster, everyone was at the scene, inspecting the damage. Thomas Lamb, the contractor, was an experienced builder. He and his brother William were responsible for a great deal of the construction in Brooklyn during this time.

They built everything from row houses to churches, theaters, banks and office buildings. They were the go-to company for most of the prominent architects of the day. Thomas Lamb was also a member and trustee of this church. He was one of the first at the site. He arrived at a scene that looked as if a bomb had gone off.

Mrs. Mott’s house was crushed. It looked like a dollhouse, with open walls, the contents of the house crushed and sodden from the rain. The mansard roof of the house had been torn off, and had crashed into the rear extension of the house next door.

Oddly, one of the windows from the roof lay in the yard, its glass still intact. Next door, the other three walls of the church were still standing, but the back wall was gone. Lamb told reporters he had never seen anything like this in his life.

He showed the Eagle reporter intact pieces of the rear wall lying to the side, the mortar still holding the bricks together. They looked at the foundation. It was smooth and unbroken.

Lamb surmised that the wind had rushed into the roofless structure. Because the front and side walls all had openings for windows and doors, the force of the wind was dissipated through the openings. But the rear wall was solid, with no place for the wind to go.

So it had picked up the wall clean off its foundation, and hurled it into the Mott house. Lamb went on to explain that although it was winter, and it took longer for mortar to set, the church walls had been solidly and correctly built.

He also said that the inspectors had already been there, and would be filing their report. He also expressed his sorrow over the loss of life and property.

The reporters also visited Mrs. Mott, who was staying with friends. She was in pain, both physically and emotionally, but spoke to the reporter. She said the family had been sitting in the parlor for most of the evening because of the storm.

She said no one had said aloud that they were worried about the walls falling down on them, but they had all thought about it. The whole thing had happened so quickly, she really didn’t remember what happened, or how she and her daughters had survived. She couldn’t believe her grandchildren were dead.

Rev. Foote, the pastor of Throop Avenue Presbyterian told the reporters that the two teenagers would have their funeral at the church, and would be buried in Rye, with their father.

The church would pay for the funerals and all of the other costs. The dead girl, Mary Purdy, had been the only member of the family to be a member of the church, but he had known the entire family, including Mary’s brother, David.

The family picked through the wreckage and salvaged what they could, which wasn’t much. What the wind and collapse hadn’t destroyed, the rain had ruined.

In spite of that, a couple of weeks later, someone was arrested for selling a couple of lace and velvet gowns that had been pulled from the wreckage by a workman. He had sold them to a used clothing seller. Apparently, the clothing had been marked with the Purdy name.

The builders began cleaning up, and set about to rebuild the walls and finish the church. The building inspectors filed their reports and a coroner’s hearing was scheduled to assign blame for the disaster.

The Brooklyn Eagle took to its editorial pages and for two days railed at the ineptitude of the Department of Buildings. Apparently, no one at the department was able to tell anyone how many times the building site had been inspected, who had inspected it, or what they had actually looked at during the inspection.

The paper charged that the investigation into the entire affair be carried out with diligence and a search for the truth.

The church, the builders, nature itself , or a failure by the department – whatever the reason for the disaster, the Commissioner of Buildings needed his office to deliver a fair and unbiased report, and take steps to insure that this sort of thing never happen again. The editorial writer did not hold out much chance of the Buildings Department to be able to do that.

The coroner’s inquest took place over a few days, beginning at the end of that January, 1890. Independent builders testified as to the superior quality of the materials and the work. They saw no shoddy materials, construction practices or work.

In fact, they said, the building was built far above the standard codes. Masons and carpenters who were employed on the site testified to the same. The mortar used was the best, the bricks a superior brand, those working on the building knew what they were doing.

Thomas and William Lamb testified, as well. So did Mrs. Mott and Emma Purdy, the mother of the two children, and the inquest also heard from Rev. Foote, as well.

The inspectors said that they had noticed that the wall was not supported by any bracing or wooden scaffolding at that time. Several builders then testified that braces were not always necessary in a structure like this.

One testified that sometimes braces can weaken a building, as they don’t allow the bricks to take the load for themselves. More than one experienced builder and mason testified that given the quality of the materials, the construction methods being used, and the building’s design, they would not have braced the walls either.

Several people testified as to the weather conditions, the damage the winds had inflicted on other locations, and the fact that no one can plan for random acts of nature. The inquest also heard from the police and fire departments, and the building department.

The jury of six men deliberated for hours, and came back with split verdict. Four men said that the walls should have been braced, whether they needed it or not, and the blame for the disaster lay on Thomas and William Lamb.

Two other men vehemently disagreed, saying that the fault lay solely with the wind and nature, and no human hand was to blame. Since there was no unanimous consensus, the official blame for the disaster would lie with the builders.

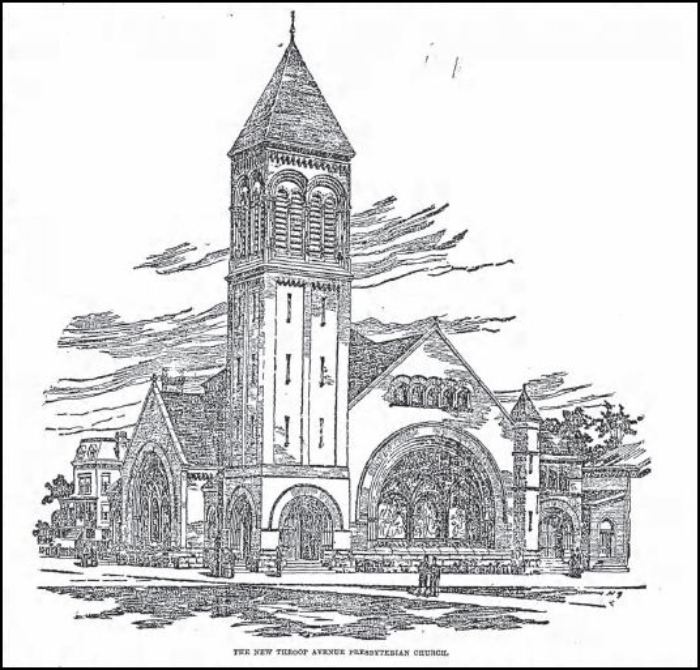

In spite of the verdict, Thomas and William Lamb’s company went back to work and completed the church. They came to the church and announced that they would pay for half of the construction. The church was completed in 1891 and dedicated late that year.

A search of the newspapers led to no other news about Mrs. Mott, Mrs. Purdy, or the rest of the family. It is not known if they sued the church, the Lambs, or what happened to them. Like many victims, as soon as the news moves on to new disasters, they were forgotten.

Throop Avenue Presbyterian was an active congregation. They had clubs for children, charitable activities and was one of Brooklyn’s most well-known churches. Rev. Foote was one of the city’s most well regarded ministers, and he was also asked to speak all over the city.

While out and about, he contracted typhoid fever, and died within a week of coming down with it. It was most unexpected, and a devastating blow to the church community. He died on Dec. 19th, 1905, only three or four days from celebrating his 32nd anniversary at the church.

His wife had also contracted typhoid, and was sick for many months afterward, too ill to attend her husband’s memorial service a month later.

After a long search, the church hired Dr. Allan Douglas Carlile as pastor. Dr. Carlile came from Massachusetts to be at Throop Avenue, and was soon well respected and popular. He was the minister on hand when the church suffered its next disaster.

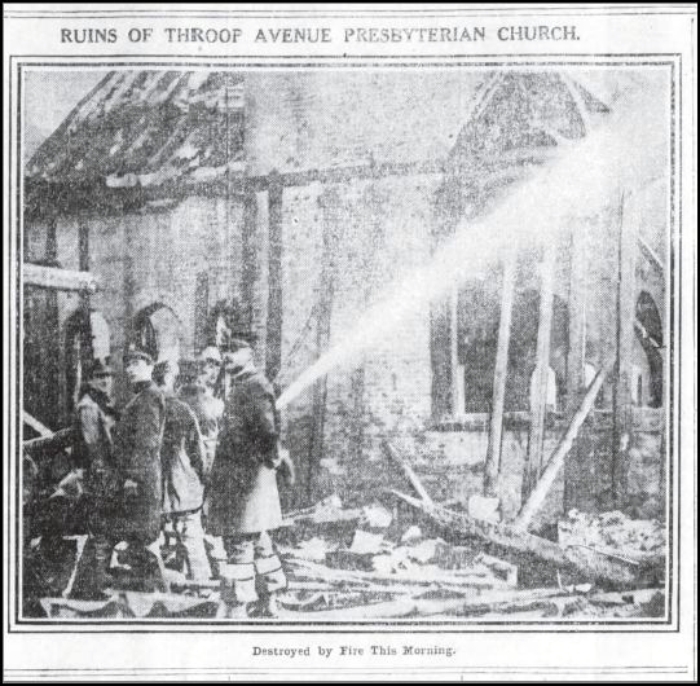

On November 19th, 1910, the church caught on fire and burned to the ground. It happened during a time when four other Brooklyn churches also burned down, and many thought a pyromaniac was on the loose. But this was different. It was not arson, but an electrical fire.

Throop Avenue Presbyterian had been considered one of Brooklyn’s most beautiful churches. The congregation decided to rebuild, but not there. There were too many memories. Their next church building would be further into Stuyvesant Heights. For more on that building, see today’s Building of the day, later today.

(Sketch: Brooklyn Eagle, 1890)

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment