Past and Present: The Folly Theater on Debevoise Street in Williamsburg

A look at Brooklyn, then and now. Theater and live entertainment have long been an important part of our culture. We have a need to be entertained, amused or moved by the actions and talents of those who have an equal need to perform. Before our entertainment was delivered to us by devices we keep…

A look at Brooklyn, then and now.

Theater and live entertainment have long been an important part of our culture. We have a need to be entertained, amused or moved by the actions and talents of those who have an equal need to perform. Before our entertainment was delivered to us by devices we keep in our pockets, or sit in front of in our homes, there were theaters, concert halls and auditoriums. Every city had at least one theater district. Here in Brooklyn, we had several.

There were so many theaters and entertainment venues being built in the 19th and early 20th centuries that architects could specialize in designing theaters and concert halls, and make a good living. The needs of a theater space were many and specific. In some ways, a designing a theater could be very similar to designing a church or temple, so sometimes, architects who specialized in one moved easily into designing the other. Given the natures of church and theater, it’s a rather ironic combination of the sacred and the sometimes profane.

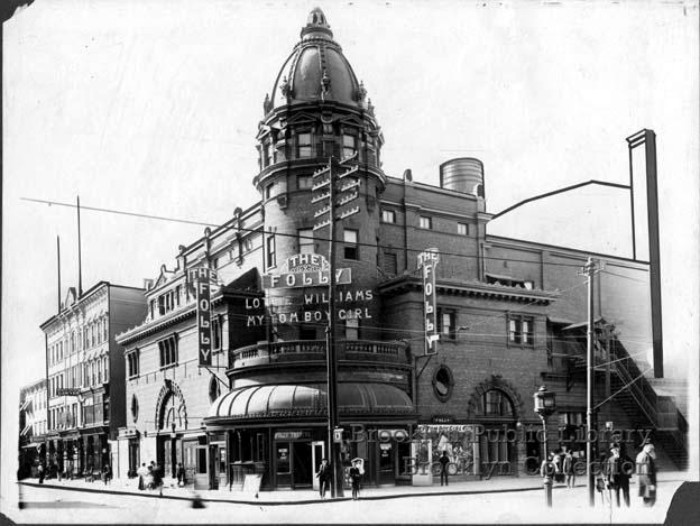

The firm of Dodge and Morrison designed churches. Stephen Webster Dodge and Robert Burns Morrison were well known for their church designs throughout the East Coast, as well as for their other design skills. Here in Brooklyn, they were responsible for the beautiful addition to the Bedford Central Presbyterian Church on Nostrand Avenue in Crown Heights, between Dean and Bergen Streets. Dodge and Morrison also designed theaters, and one of their best was the Folly Theater, which stood on the corner of Debevoise Street and Graham Avenue in Williamsburg.

The Folly was built as a vaudeville house, and opened in 1901. Its design was a bit of a mish mash of classical and Victorian elements, vaguely reminiscent of Parisian architecture, with a large central domed tower that soared over the top of the building. The marquees were prominent on the face of the building itself, and the entire structure self-advertised very well. The newspaper critics of the day loved it, and called the Folly one of the most beautiful and classy theaters in Brooklyn.

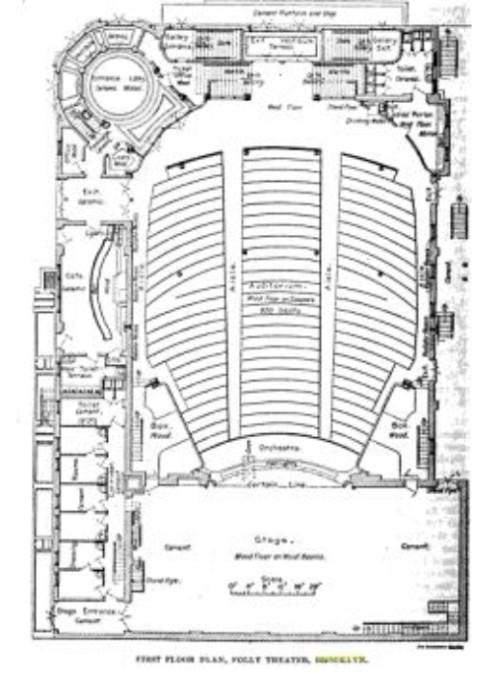

Inside, the décor was opulent and very French Baroque, with lots of gilding, classical statues and ornament. The floors at the entrance were marble mosaics, and the interior was decorated with allegorical and figurative paintings of the muses. There were men’s and women’s lounges and all kinds of creature comforts and amenities.

As impressive as all that would be to theater-goers, the real marvel of the theater was the implementation of new rules for theater design, which resulted in a more fireproof interior, more exits and new safety measures built in. Brooklyn had too many tragic theater fires. There were also new innovations in set design and the movement of scenery, enabling the stage hands to get sets on and off the stage more quickly, always a good thing in theater, especially in variety shows.

Although the venue opened as a vaudeville house, they soon expanded to include longer plays and melodramas, along with the variety shows and motion pictures. Over the years, many of the day’s most famous variety acts played here, and many of the New York stages most popular actors and actresses had plays written for them which debuted here and ran for months, alternating with the vaudeville shows and movies. Fanny Brice and Will Rogers played here.

One of the most popular acts was that of Williams and Walker; Bert Williams and George Walker, the black vaudevillians who were among the first black superstar performers. They first performed at the Folly in 1908. Corse Payton, the “world’s best bad actor” played here, as did the great Houdini. Much later, in the 1930s, the Folly was one of the first venues for a teenaged Jackie Gleason. He was a part-time master of ceremonies for the live variety shows here, every Monday and Friday night, one of his first theater jobs.

Because this was such a popular theater, all kinds of activities, from the strange to the dangerous, took place here. In 1907, passers-by would have seen a chain gang of prisoners walking back and forth in front of the theater. The group of six men was dressed in the classic black and white striped prison uniforms, marching around while guarded by a uniformed guard with a wooden gun. They were all actors, advertising a new melodrama at the theater called “Convict 999.”

In 1915, the captain of the nearby police precinct, William H. Ward received death threats when he went over to the Folly to disperse a group of young men hanging out in front, during the day. Captain Ward had recently arrested several young drug dealers who were selling packets of cocaine to young women in the theater. The coke was packaged to look like face powder. This was in 1915!

In 1929, Hollywood fantasy became reality as a group of armed men robbed the box office of the Folly, and shot their way out of the theater lobby. Over 2000 panicked people ran into the streets trying to dodge the bullets. Like a gangster movie playing on the screen, the robbers waited until the show was just beginning and went to the box office. They actually announced, “Stick ‘em up,” and robbed the managers of the theater as they were counting the proceeds. An usher had run out to get the police, unseen by the gunmen.

Four policemen were soon at the scene as the men ran through the lobby. They all opened fire, and in the gun battle, men were wounded on both sides. The robbers escaped in a waiting car, pursued by the police in two taxicabs that they had flagged down. Both sides were still firing on each other. The bandits weaved through traffic and got away, no doubt to the relief of the cab drivers. The car, which was later found to have been stolen, was found with some of the money still inside, along with a lot of blood. It was surmised that several of the gunmen were wounded in the robbery. They got away with over $2,500 dollars.

The theater remained a vital part of East Williamsburg’s entertainment life until around the beginning of World War II. Vaudeville was long dead by that time, but in addition to the movies that ran there, the theater was still home to variety shows and comedy acts. It was also used by community groups, most especially Jewish groups, for large gatherings. Passover celebrations for Jewish youth were held here in the 30s and 40s, with lectures, music and celebration.

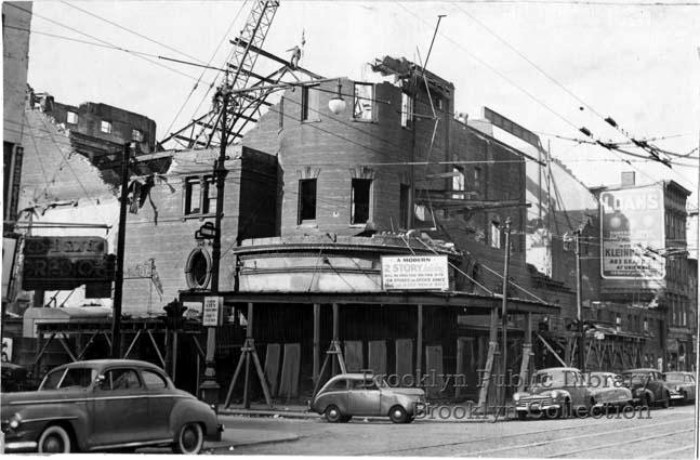

But by 1940, the theater was closed forever. It sat closed and empty and decaying for almost ten years. In 1949, the theater was torn down, supposedly for a new two story office building that would rise on the site. The theatre had been so well built, it was a hard demolition to accomplish, and it took a long time. The half destroyed theater stood for many months like a bombed out remnant of the war, prompting the Brooklyn Eagle to say, “Nothing looks more abject than a dying theater, and the gutted Folly stands steeped in misery.” The current one story building housing Banco Popular was built in 1951. GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment