Walkabout: Stylish Englishman Steals From Brooklyn Bank -- a Cautionary Tale From 1893

Bryce Arthur Whyte was as English as Queen Victoria. He had a plummy upper-crust sounding name. He was handsome, with a slight blonde mustache and carefree air, well-mannered and, apparently wealthy. Whyte came to America in 1888, the son of a Liverpool merchant who had made a great deal of money in the East India trade. He…

Bryce Arthur Whyte was as English as Queen Victoria. He had a plummy upper-crust sounding name. He was handsome, with a slight blonde mustache and carefree air, well-mannered and, apparently wealthy.

Whyte came to America in 1888, the son of a Liverpool merchant who had made a great deal of money in the East India trade. He decided to make money — so that he wouldn’t be bored, as he told friends — and got connected with the founders of the Wallabout Bank.

When the Bank opened its doors on the corner of Clinton and Myrtle Avenues later that year, Bryce A. Whyte was an assistant clerk, responsible for taking in and recording deposits.

Bankers are not by nature a trusting people. The bank had asked for and received a guarantee of trustworthiness for young Whyte. The Guarantee Corporation of North America, located in Manhattan, put up a $10,000 bond as security for his honesty.

But unbeknownst to everyone in his new American home, all was not well in Whyte’s well-presented life.

Whyte Wasn’t Wealthy, But He Spent Like It

Whyte may have grown up in the lap of luxury, but had been rudely dumped into reality. Before he left England, his father’s business had failed, plunging the family into genteel poverty. He could no longer continue his extravagant lifestyle in England, so he came to New York.

He knew he couldn’t front an aristocratic lifestyle in Brooklyn or Manhattan, so he moved to Staten Island and got an apartment there. He told everyone he was “in banking” in Brooklyn, intimating that he was a senior official in a bank.

He was soon involved in the Staten Island social set, throwing money around in lavish parties, betting on horses, riding his own fast horses, and dressing like an English lord in an adventure novel. He was known among his peers as a most excellent fellow and a fun guy. He loved to party, and he bought his friends extravagant gifts.

Staten Island’s isolation meant his worlds remained separate. He went to work every day at the bank, drawing a salary of $1000 a year. That was a decent salary for the times, but nowhere near enough money to explain his extravagant standard of living.

Humble bank clerk by day, bon vivant by night. How was he doing it?

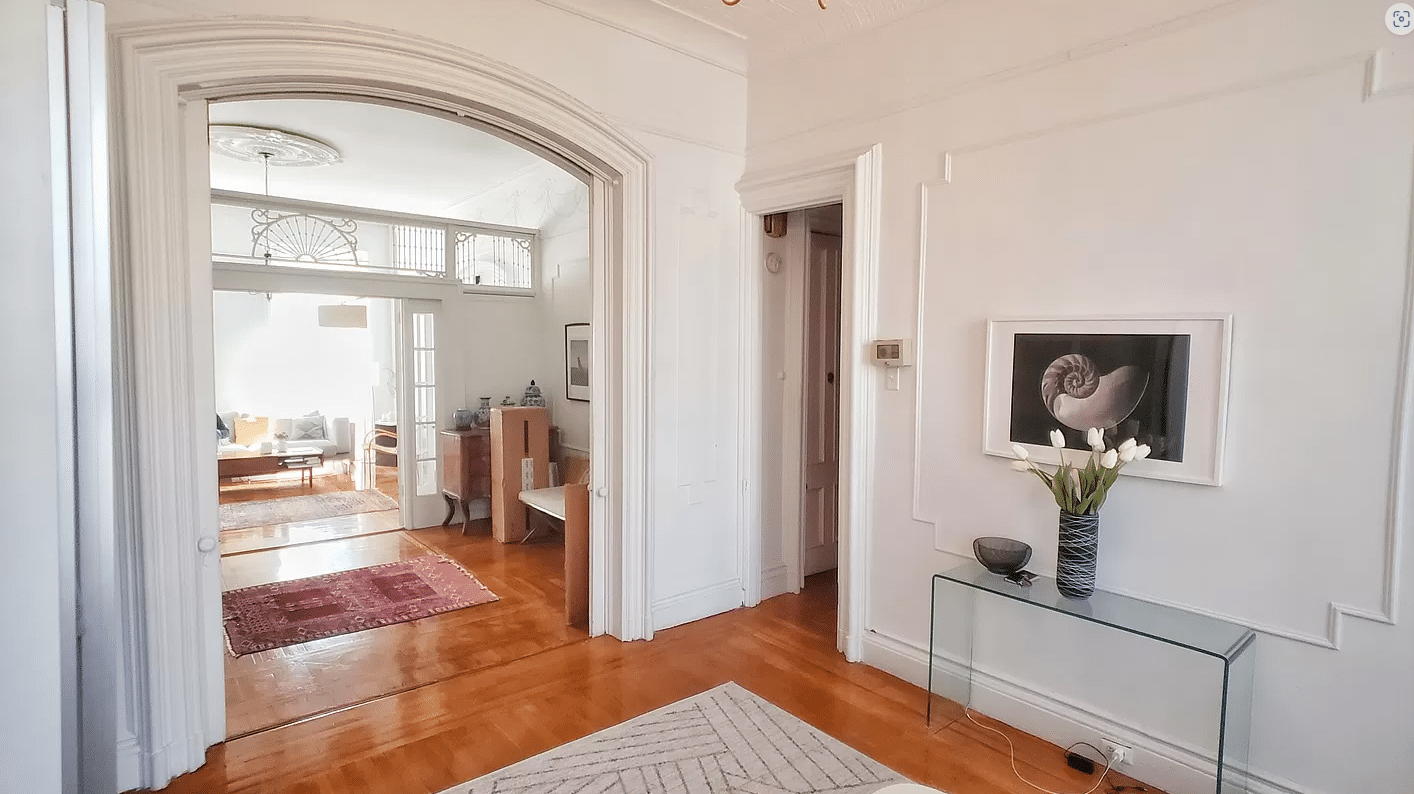

Former home of the Wallabout Bank, Corner of Clinton and Myrtle Avenues, via Google Maps

Whyte Was Stealing From the Bank

One weekend in January of 1893, a Miss Ludlum of Brooklyn went to visit friends on Staten Island and take in the social activities at New Brighton. She had a great time socializing with other wealthy young people, taking in the races, dining and dancing and having fun. Chaperoned, of course.

When she got home, she was telling her parents about the fun she had, and mentioned a handsome young man named Bryce Whyte, who was a banker here in Brooklyn. He was in the thick of it all, she said, and was so dashing, so elegantly dressed, and so obviously wealthy.

Her father said, “Bryce Arthur Whyte?”

“Yes, he told us that he was a high up in one of the banks here in Brooklyn. You must know him.”

“I see,” said her father, Edward Ludlum, one of the directors of the Wallabout Bank, Bryce’s employer.

The Bank Checks the Checks

Ludlum got in contact with his bank, which had the Guarantee Corporation of North America check out young Whyte’s background – current and past.

They then turned to their books. The numbers were not adding up — there was money missing and checks which had not been turned in.

Most recently, two checks had been given to Mr. Whyte for deposit. They were from John Englis, who owned the building the bank was in, and was the brother of Charles Englis, the president of the bank. One check was for $500, the other for $543.60. Both had been recorded as received, but neither check had been turned in as a deposit.

Whyte stopped working at the bank that month, before the jig was up. A warrant was put out for his arrest, and he was picked up at a hotel in Manhattan. He didn’t look too surprised when the deputies escorted him back to Brooklyn and the Adams Street Court.

He was charged with stealing the two checks, with further charges to come. He appeared before the judge, “the embodiment of a reckless young man repentant of his foolishness,” as the Brooklyn Eagle reported.

Whyte Is Fashionably Apologetic

Whyte was dressed in a very fashionable dark blue suit. His trousers had a permanent crease in them, as was the fashion, and he was wearing a mackintosh coat with a cape, ala Sherlock Holmes. The paper said scornfully that the hands that emerged from the cape, “had a whiteness and softness of a woman’s.”

He was holding a light grey derby hat in his hands, which the paper also noted was quite the fashion for stylish young men. It also said that his face “was not a strong face. An incipient blonde mustache traces a line along his upper lip. He looks honest.”

Whatever else his faults, Bryce Whyte knew when the party was over. When asked for a plea, he said “Guilty.” That drew gasps from the audience, and more than one sympathetic glance towards him, and glares at the District Attorney. He was taken away to be booked, photographed and put up in the notorious Raymond Street Jail until his hearing.

Of course, the newspapers ate this up. The story made the Brooklyn and Manhattan papers, and was carried by New York State papers as far away as Syracuse and Oswego.

While he was in jail, he wrote to the president of the Wallabout Bank, and promised that he would pay back every penny, if given the chance. He was truly sorry.

Reporters came to visit him at Raymond Street, but he wouldn’t meet with them. One reporter managed to find out that most of his fellow prisoners thought it was great that he had managed to enjoy his ill-gotten spoils, and thought he was a fine fellow. Whyte didn’t want to talk to them, either.

Since he had pleaded guilty, the judge granted him a week’s stay at Raymond Street before passing sentence. Some of his friends wanted to get him a famous lawyer, which he declined. Meanwhile, testimonials as to his character and excuses for his behavior began appearing.

Excuses, Excuses. But Whyte Still Confesses

The Rev. Dr. Trumbull of the Episcopal church in Staten Island that Bryce attended told reporters that his congregant was not responsible for his actions. He said Bryce had been thrown from a horse three years before and had landed on his head. Ever since then, he had done things he knew to be wrong, but just couldn’t help himself.

The people at his bank scoffed at that one, saying he had managed to keep his accounts correct, and to concoct an elaborate and successful embezzlement that he kept going for two years. Landing on his head hadn’t affected that part of his life.

When he appeared before the judge a week later, Bryce Whyte looked worn and tired. Jail was not agreeing with him.

But, to his credit, he made no excuses for his behavior. He had indeed stolen the Wallabout Bank’s money, and spent it all on a sham lifestyle, he said. He had telegraphed his father asking for money, but his father could not help him.

Since the Guarantee Corporation of America had a $10,000 bond on him, the bank got paid back. They were happy. Whyte’s friends came through too. They paid the $10,000 back to Guarantee. It was up to the judge to determine how severe Bryce’s punishment would be.

Bound For a Country Club Prison

The judge was lenient, sentencing him to the Elmira Reformatory. Unlike Sing Sing or hard labor penitentiaries, the Elmira Reformatory was a late 19th century experiment in prison reform, taking in non-violent offenders. It was their version of a country club prison.

Prisoners were kept there until it was deemed that they had paid their debt to society. It is unclear how long Bryce Whyte was incarcerated, or what happened to him when he was released. He disappeared into history.

The Brooklyn Eagle gets in the last word, with an editorial penned when Whyte plead guilty. They were outraged that this man had fooled so many, and had stolen not only money, but a lifestyle that he couldn’t afford.

He knew that if he had elegant apartments and fast horses in Brooklyn he would be suspected. So he went to Staten Island to live. He knew he could be a swell there without the knowledge of his habits coming to the ears of bank officials here.

This preparation for knavery is too evident to be mistaken…He may have been active in creating the impression that he was a capitalist.

It is difficult to find any extenuating circumstances in this case. He was too deliberate in his preparations to deceive. Good clothes do not make an honest man, neither do good looks nor wealthy parentage.

It is feared that imprisonment will not be effective, either, in the case of young Whyte. His father probably spells his name “White.”

Ouch!

Above illustration – Interior of First National Bank of Chicago, 1883, via the Office Museum.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment