Walkabout: Rufus L. Perry and Son, Brooklyn Pioneers, Part 2

Editor’s note: An updated version of this post can be viewed here. During the latter part of the 19th century, Rufus L. Perry Sr. was one of Brooklyn’s most prominent ministers. Like most of Brooklyn’s leading Protestant clergymen, he had a doctorate, was widely published, and his sermons were quoted in the religion pages of…

Editor’s note: An updated version of this post can be viewed here.

During the latter part of the 19th century, Rufus L. Perry Sr. was one of Brooklyn’s most prominent ministers. Like most of Brooklyn’s leading Protestant clergymen, he had a doctorate, was widely published, and his sermons were quoted in the religion pages of the Brooklyn Eagle. The fact that he was African American, and had been a slave in childhood, was seen as remarkable. Part 1 of our story recounts his life. Next, read Part 3 of this story.

But as remarkable as Rev. Perry’s life story and accomplishments were, the world hadn’t seen anything yet. His eldest son, Rufus L. Perry Jr., was about to break the mold.

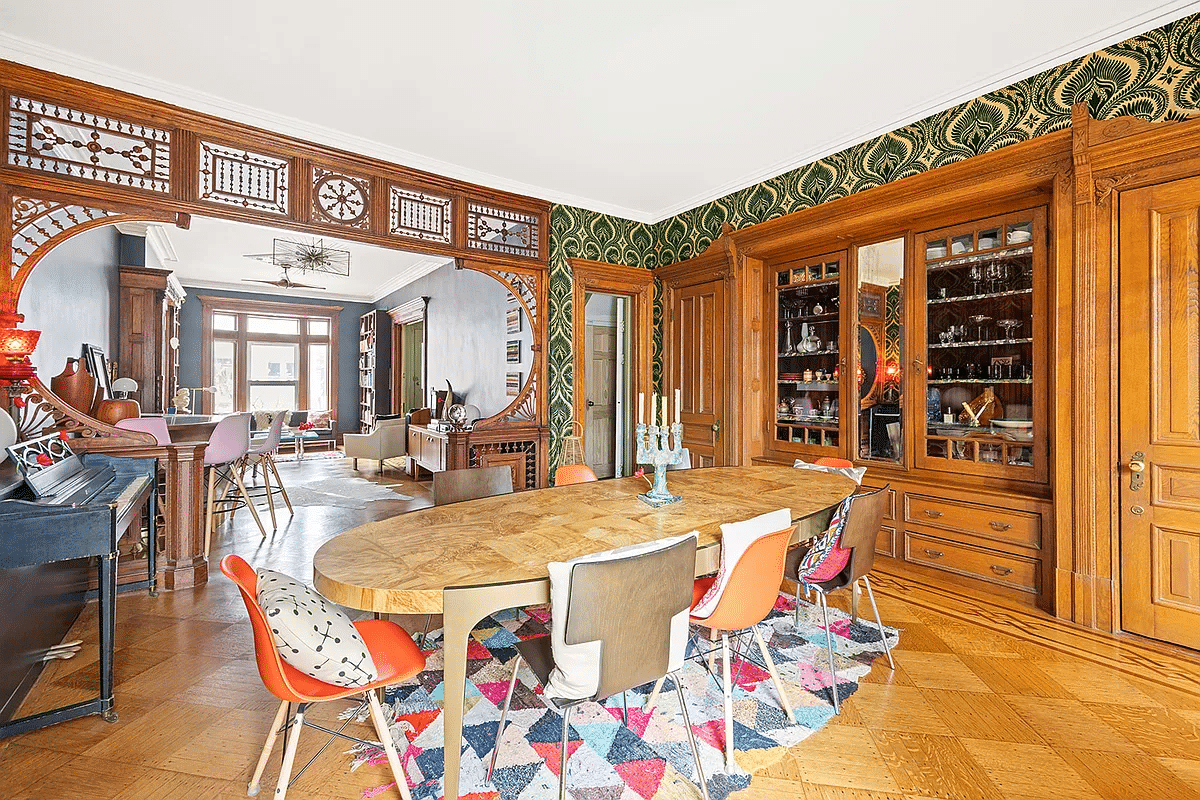

Rufus Jr. began his life on May 26, 1868, born here in Brooklyn to Rev. Perry and his wife Charlotte. The family lived in a home in what is now Crown Heights North, on St. Marks Avenue, between Albany and Schenectady avenues.

Life for black folks in late 19th century Brooklyn was not easy. The law prohibited many overt forms of discrimination, but the reality was that most black people in Brooklyn lived on the fringe of society.

The schools and everyday life were segregated, and most African Americans were laborers or relegated to service jobs, while a small black middle and upper-middle class struggled to find acceptance and equality in the workplace and society.

The Perry family was part of this emerging black upper-middle class, which consisted of clergy, doctors, lawyers, undertakers, business owners and teachers.

Rev. Perry and his wife raised their children to believe that they were the equals of anyone. They were encouraged to aim high, and become whatever they wanted to become in the world. They should not allow other people’s prejudices to hinder their progress. Young Rufus took that to heart. He was also really, really smart.

Brooklyn Standard Union, 1922

Rufus Perry Jr. matriculated through Brooklyn’s public schools, and then went to New York University for college and law school. He graduated from NYU Law at the top of his class in 1891.

He astounded his professors, and probably annoyed the hell out of his classmates, by writing his exams for entrance to the Bar completely in Latin. He also spoke and wrote fluent Greek, Hebrew and French.

His teachers were so impressed by his exams, they made copies and made all of the students read and learn.

Perry was asked to be the orator at his law school graduation, and give the class speech. It was such a novelty for a black man to do so that the news made the New York Times, as well as papers across the state.

The Times noted that his speech was entitled “Liberty as Embraced in the Constitution of the United States.”

Rufus L. Perry, Esq., was soon out on his own as a lawyer. He set up his offices at 375 Fulton Street, in the heart of the civic district.

For the next thirty years, he was “the Negro lawyer, Rufus L. Perry.” Sometimes he was the “Colored lawyer, Rufus L. Perry.” Every once in a while, he was simply Rufus L. Perry, lawyer. It all depended on where he was and who his clients were, and what papers covered his cases.

He had quite a varied roster of clients, black and white, male and female. The usual crowd at the courthouses got used to seeing “the Negro lawyer” there. He represented clients in civil and criminal cases, and he generally won.

His cases ranged from defending a young black woman who was accused of attempting suicide, an offense that could land you in jail, to representing a group of homeowners in Queens who sued the developer who built their houses.

He was able to have the charges dropped in the first case. The second case took place in 1906. Perry represented five Flushing homeowners who had purchased homes that were under construction. After moving into the completed homes, the homeowners soon found themselves with leaking roofs. On inspection, it turned out that the builders had substituted a cheap composite paper tile for the asbestos tiles specified.

Perry took the case to court and won. This was one of the few times in the papers that he was simply “Lawyer Perry from Brooklyn,” with no reference to race.

Kings County Courthouse via Brooklyn Public Library

Aside from his full schedule as a lawyer, Perry was also very much involved with varied other interests. He was a longtime correspondent to a French language newspaper published in America called Courrier Des Etats-Unis.

In 1906, he turned down a position in the consular office to Haiti. He did represent the president of Haiti, Pierre Nord Alexis, for several years, and was his official attorney.

He also continued his studies in Hebrew, and compiled a Hebrew grammar book.

In 1912, he made news around the country when he converted to Judaism. He had his first name changed to “Raphael.”

The newspapers were full of the story of the Negro who became a Jew. He was said by all to be the “first of his race to do so,” a claim that is by no means accurate.

Rufus Perry was a passionate defender of and advocate for the black community, and like his contemporary W.E.B. DuBois, insisted that the white world treat him as an equal, both in the courtroom and in public. This stance caused some severe cases of ruffled feathers.

Postcard circa 1910, via Ebay

In 1899, he caused a stir when he proposed to establish a “Negro colony” near Jamesport, Long Island. He wanted to buy property and establish summer homes for well-to-do black families.

The horrified landowners of Jamesport vowed to do whatever it took to stop him. There wasn’t a lot of available land, and they promised to pool money to buy up every inch of it in order to stop the Negroes from establishing a beachhead there.

It turned out that Jamesport already had a small black population a mile away from town, in an area called “Cum City.” It was named after Cummy Boston, an 80-year-old man who had been the area’s first settler.

The hamlet consisted of about ten houses along a road, with a church at the end. Boston and the other black families there had been employed as local farm workers before the area had become dominated by the second homes and estates of wealthy New Yorkers.

The Brooklyn Eagle sent a reporter out to Jamesport to get the opinions of the locals to the news of possible new neighbors. Boston, known by everyone as “Uncle Cummy,” was the only person interviewed who thought it was a great idea. “Golly, won’t that be fine,” he said.

A wealthy white landowner in Jamesport had an opposing view. “In my judgement, to dump a gang of Negroes who have been driven from the south because of the crimes of their own kind and for the misdeeds of themselves, into this delectable country is an outrage that beggars description and should be resisted by any person who has an interest in Long Island at heart.”

Perry seems to have abandoned the idea, probably more because he had so much on his plate than because of the racist negativity. He wouldn’t have had a problem taking on anyone who opposed him.

His insistence on equality for himself and those of his race made him a hero and role model in the black community, and his intelligence and skill in the courtroom garnered him much respect in the courts. But not everyone was impressed. Some thought he needed to be made aware of where his place really was.

Next time: Rufus L. Perry Jr. gets married, and gets involved in the blood sport known as Brooklyn Politics. Meanwhile, his enemies conspire to end his legal career, but it won’t be that easy.

Part 3: Rufus L. Perry and Son, Brooklyn Pioneers Conclusion

Thank you for sharing this story….It’s ashamed that even back then no matter how smart or successful you became people believed that he should know your place due to the color of your skin….